Today’s creative director of ILM’s Sydney studio talks Jar Jar Binks, digital armies, and working with George Lucas on the project of a lifetime.

Kicking off the highly-anticipated prequel trilogy, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace arrived May 19, 1999. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Phantom at 25,” a special series of interviews, editorials, and more.

Fairly late in Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999), as the heroes plan their concerted attack on the Trade Federation army occupying Naboo, Jar Jar Binks and Boss Nass have a brief moment together. They walk through a forest, the shorter and squatter Boss Nass’ arm wrapped around Jar Jar’s taller and lankier shoulders. The onetime Gungan outcast is now in rising favor with his people’s leader, and Jar Jar enjoys brushing off Boss Nass’ adulations with mock-humility. It is only when Nass tells Jar Jar that he is to be made a general that Jar Jar breaks character and faints with surprise.

The moment is portrayed in one shot as the camera pans from right to left. The characters’ equal sense of playfulness and pomposity is fun and believable, communicated in large part by their body language and distinct inflections of speech. It’s a type of scene that could be in any kind of movie. What makes this scene different from most others up to that point in time, however, is that both Jar Jar Binks and Boss Nass are computer-animated by the artists at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), with voice performances by Ahmed Best and Brian Blessed, respectively.

“You have two characters who don’t exist in the world as the prime focus of that shot,” explains Rob Coleman, who served as animation director on The Phantom Menace and today is ILM’s creative director of the Sydney studio. “We had these little mini-triumphs as an animation crew, and were earning more and more trust with [director] George [Lucas] and the editors that we could sustain this and handle it. In the early days, they would really only cut to us if the characters were talking, and over time, especially into Attack of the Clones [2002], we earned those non-verbal shots.

“In live-action, we see it all the time,” Coleman continues, “an editor cuts to a non-verbal character so that the audience sees the reaction and actually learns more about the scene from the reaction than from what they’re hearing offscreen in dialogue. It was really important to me to get to that point. Along that journey, there were many shots with sustained physicality of the characters, what we call body-mechanics shots. They’re acting, in character, sharing the screen with real people. Subconsciously, the audience can say, ‘Well, I know that person’s real but that other one is fake.’ Once we got to a point where they weren’t thinking that anymore, then we were in the place we needed to be.”

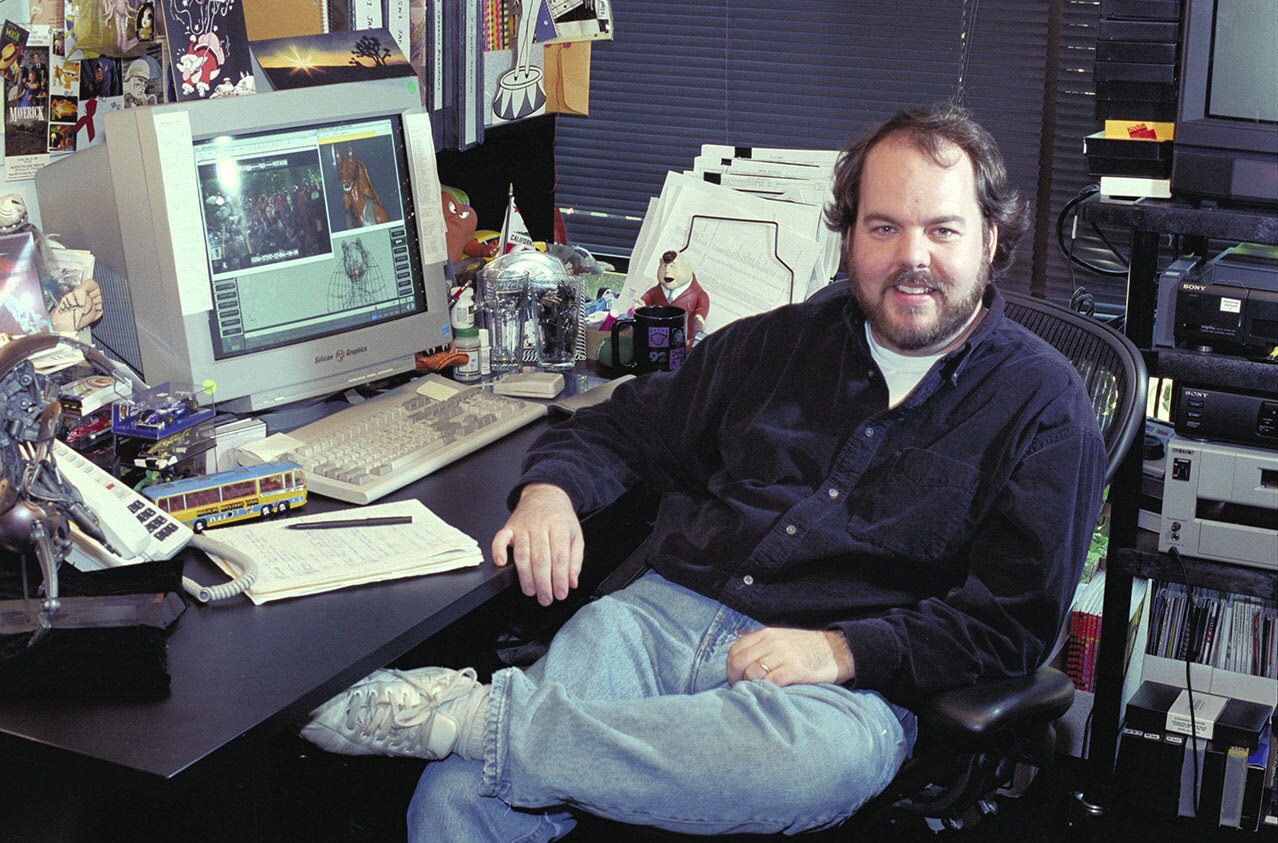

Coleman was a relatively new member of the ILM crew when he started work on The Phantom Menace. Hired in the autumn of 1993 from his native Canada, he soon proved himself on client productions like The Mask (1995), Dragonheart (1996), and Men in Black (1997). As ILM readied the new Star Wars production, it became clear that not one but three visual effects supervisors (John Knoll, Dennis Muren, and Scott Squires) would be required to oversee the massive number of effects shots, the first movie ever to break 2,000. Coleman however, would be the sole animation director (a title that was perhaps the first of its kind, and an ultimate surprise to its holder), responsible for a team of more than 60 animators across the entire film.

“What I remember is that they didn’t want to divide up the performances,” Coleman says. “They wanted one person looking after all of them. [Then ILM president] Jim Morris was a great mentor to me, and one of the things we would talk about was the scale and scope of the show. Men in Black was 200 shots. Suddenly, this was 2,000 shots and digital characters were present throughout the entire movie. Jim told me that I’d have to delegate with authority. By authority, I mean that you have to tell them what you need from them, and also tell them what they can expect from you. You can’t micromanage them. You can’t be over their shoulders. You would never get the movie done. Hearing Jim tell me that, I surrounded myself with some great lead animators and delegated. I mostly stayed at the high level, looking at the consistency of the performances.”

The process, though, was something Coleman had to learn on the job. “I kind of lost my compass reading there during the early days of The Phantom Menace,” he says. “I had defined myself as an animator, and now I wasn’t animating. So I was trying to find my way in terms of what my contribution to the show was.”

Among the first scenes Coleman and his team decided to tackle was an exchange between Jedi Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) and Watto (voiced by Andy Secombe) in the latter’s junkyard on Tatooine. “It was a very cautious decision to pick that scene first,” Coleman says. “It’s a scene buried in the middle of the movie. One never starts with the first shots because you know that you’re going to learn over the course of the project. Some of the first work you do can be the weakest. But in this particular case, Andy’s voice performance was so fabulous and I loved the character’s design. I could see him in my mind’s eye and act it out. I could just feel him. So we had a really strong group of animators on it. There were just two characters with Qui-Gon and Watto, so it was more controlled.”

All the same, the digital Watto is performing opposite Liam Neeson, only a few years removed from his Academy Award-nominated performance in Schindler’s List (1993). The key to matching the live actor’s performance was in the substance of Watto’s character. Although the Toydarian is clearly an antagonist, there is noticeable depth to his personality, even a bit of gentleness and sympathy for young Anakin Skywalker. With Lucas’ direction and Secombe’s vocals, Coleman led the crew through this initial scene.

“You have text in the script,” Coleman says, “and then subtext, which is in the head of the character, and that has to be communicated by the director to the voice actor and then onto the animators. Subtext can be longing, loving, any of those emotions. You’re going to play the scene differently depending on what’s in your head. I was always interested in subtext and some of the best conversations I had with George about any of the characters was regarding that.”

Coleman took an in-progress version of Qui-Gon and Watto’s junkyard exchange to show Lucas during principal photography in England. “It gave George the confidence he needed that he’d made the right decision to use these digital characters,” says Coleman. “He was excited about it, and showed it to Frank Oz, who was doing the puppetry for Yoda. I was overwhelmed to have the job and kind of freaked to be working that closely with George, but once I could see him responding to the characters, I could be more open and collaborative and ask him questions.”

Once filming had wrapped, more than a year of work lay ahead. Though he had plenty of experience, Coleman admits that he struggled at first under the pressure. “A few months into work after we came back from the shoot, the scale, scope, and enormity of this project was beginning to weigh heavily on me to the point where I wasn’t sleeping very well at night,” he explains. “I was badly suffering from imposter syndrome. I was questioning how and why I got the job, and I didn’t know if I could do it. I was 19 when Return of the Jedi [1983] was released, and I knew that the world was waiting for another Star Wars film, millions of people. I kept thinking about them, and I didn’t want to let ILM down, and certainly didn’t want to let George down.

“I eventually got to the point where I was so twisted around,” Coleman continues, “that I called up Jane Bay, George’s assistant, and asked for some time with him. I sat down with George and explained that I was worried about the world’s expectations and I wasn’t sure that I could supervise the animation as well as I needed to. That’s when he laughed and said, ‘What are you talking about?’ I explained that all these people were waiting to see this movie, and George said, ‘What do you mean all these people? There’s only one person you need to worry about, and that’s me. I’m happy with the animation. It’s great. What’s the problem?’ I stammered away, ‘You like it?’ And he said, ‘Of course, I do!’ He gave me that reassurance and I went home and slept like a baby and never worried about it again. That gave me singular focus. I became focused on making George happy.”

Of all The Phantom Menace’s digital characters, Jar Jar Binks was certainly the most significant in terms of screen-time and importance to the story. Portraying the goofy yet perceptive Gungan was an evolutionary process. It began with Ahmed Best, the actor who both represented Jar Jar physically on the set and provided his voice. “Ahmed was Jar Jar,” says Coleman. “He embodied the character fully and completely to the point where the idea was that the final character would be Ahmed in the suit from the neck down and ILM would only put a digital head and ears on him. That’s because George loved the way that Ahmed moved and embodied the character.”

Soon, however, it was clear that a different approach was needed. The animators created two separate test shots for comparison, one that was key-frame animated based on Best’s movements; another that tracked an animated head and neck onto Best’s own body. “George was sympathetic to how difficult it was to track Ahmed’s body,” Coleman recalls, “but he was not convinced that the animators could provide the nuance from Ahmed’s performance that was resonating with him. That message got out at ILM, and at that point I was approached by Jeff Light. He was proto-typing what we would call motion-capture.”

Today, the image of an actor wearing a tight-fit suit covered in tracking dots that resemble ping-pong balls has become ubiquitous in popular culture. In 1997, it remained almost completely alien to filmmakers and audience members alike. But motion-capture supervisor Jeff Light and a small crew were busily pioneering a system back in San Rafael, California. Each dot on the actor’s suit could be triangulated by a series of cameras on a set, and their subsequent movements recorded into a digital counterpart that formed the ILM animators’ ideal starting place.

“We pitched it to George,” says Coleman, “explaining that there was this new technology where we could put Ahmed in a suit and track him to the digital character. If that worked, it would address George’s concerns and it would still absolutely be Ahmed’s performance. I met Ahmed in London and he was just incredibly energetic and positive, a wonderful young man. Then, because of this development with motion-capture, he came to San Rafael for a number of sessions as we worked through both the technical set-up and the artistic side.”

It was experimental work, but grounded in the tradition of the animator’s art. “Animators had been studying movement since the beginning of animation,” Coleman explains. “If you look at Winsor McCay back in the early 1900s, he was photographing people and rotoscoping or looking at them frame by frame as reference. The Disney animators did it as well. You can see footage of a young woman playing Snow White, which the animators used. And even if you look at the behind-the-scenes from Terminator 2 [1991], you can see that ILM had Robert Patrick with lines drawn across his body so they could video and study his movements.”

“When you’re doing key-frame animation and simply following live-action footage, it’s really a best guess as to the body mechanics,” Coleman continues. “It’s an interpretation. But what motion-capture gives you is an actual mathematical reality of what’s going on. That gives you all the little bits of secondary action that your naked eye can miss – the way the knee shakes when the foot hits the ground. Those kinds of things can be lost in traditional key-frame, and by result it’s a stylized version of the motion rather than a literal version of the motion. Motion-capture gives us all of this data, frame-by-frame, 24 per second. An animator might only set four or eight key-frames per second. You get more fidelity with motion-capture. We could then add animation on top of that.

“We took Ahmed’s performance and made Jar Jar jump higher, run faster, and over-accentuate things that were indicated by his body motion, what we call ‘plussing.’ Jar Jar is a stylized character. He was driven by Ahmed but we very much animated on top of that. We had no facial motion-capture whatsoever, so all of his facial animation is 100% key-framed. A lot of the additional body animation that we added was directed by George. Ahmed got us really close, and George would give us a note to delay a reach or make a stride longer or make him jump farther. Once we had the motion-capture, we could easily do that.”

Between Best’s performance during the main shoot, his vocal recordings, and his motion-capture, the animators had a suite of reference material to build on to become direct collaborators with the original actor. Although a source of comic relief in the story, Jar Jar demanded a range of different emotional scenes. “We present him as a slapstick guy, but he’s a thinking, sensitive creature who cares deeply about what’s going on,” says Coleman. Among the more subtle moments is a brief scene on Coruscant when Jar Jar speaks with Queen Amidala out of concern for their shared home’s plight. It’s a scene during which Amidala is the central focus, and Jar Jar is offscreen for entire shots, a sign of Lucas’ discipline and restraint as a storyteller.

“George always said to us that he was going to treat the digital characters like they were really there,” notes Coleman. “He would not frame up on them if they weren’t the main character in the scene. If you framed up on them every time, it would be an artificial way to shoot the scene. He absolutely did that on purpose. As another example, there’s the aerial establishing shot where you’re high over Naboo and you see the cliff-face and the city and it’s jammed full of stuff. That shot was never long enough for me. I complained at one point to George, and he said, ‘Nope, I’m cutting away from it, and if they want to see it, they can watch the movie again. I don’t want to artificially make the shot longer so people can take in all the details.’ Fair enough!” Coleman says with a laugh.

Although individual performances like Jar Jar’s posed a major challenge, Coleman identifies the climactic grass battle on Naboo as his source of greatest concern from the time. As he puts it frankly, “We had no technology to do that. We were pushing the tools to their absolute limit. I’m paraphrasing, but there’s a sentence in the script that says, ‘The Gungan army marches out to war.’ That sentence took over six months of research and development to figure out how you get an army to march out there. At that time, we could load a maximum of ten characters into a scene before it would crash. In one of those establishing shots of the battle alone, there are thousands of characters. The geniuses in the R&D team and the software department were frantically writing tools so that we could do that.”

Coleman busied himself researching war films like Spartacus (1960) and Braveheart (1995), trying to understand how large armies move, and discovering to his surprise how still most of the soldiers are. “My thinking was not to over-animate, but create things that gave a textural feeling of motion. We did little vignettes, maybe two soldiers from opposing sides fighting each other or another with a group of four. We created a library of those which we could then place into the battle and show them from any angle.” Coleman ultimately partnered with animation supervisor Tom Bertino to bring this overwhelming sequence to life.

The Phantom Menace was the start of a creative journey for Coleman that lasted nearly a decade to the release of Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith in 2005. He and the dozens of animators he led are in effect a significant part of the cast of the prequel trilogy, bringing countless characters to the screen in service of George Lucas’ vision, a vision that continues all these years later. “The perception of The Phantom Menace has changed over time,” he explains. “The younger fans loved it at the time but the older fans didn’t. Now, those younger fans are older fans, and George predicted that! He told me it was going to happen, and it’s come true.

“It was such an important film in my career,” Coleman says in conclusion. “I had been working at ILM for about four years to get to that position. The experience was everything – inspiring, overwhelming, stressful. I’m incredibly proud of what we were able to do. I still shake my head that I was able to do it, and two more Star Wars films after that. With 25 years separation, it can be strange. I know it was me, but I was much younger then, about 35 years old, so it can feel like a different version of me. I was in the right place at the right time with the right skills and temperament. I think the temperament was the most important thing, and I don’t think that part of me has changed. At least it doesn’t feel like it has.”