The veteran sound artist was among the first crew members to work on the Star Wars prequel entry.

Kicking off the highly-anticipated prequel trilogy, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace arrived May 19, 1999. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Phantom at 25,” a special series of interviews, editorials, and more.

The first person to watch the initial assembly of Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) wasn’t director George Lucas. It was then-25-year-old Matthew Wood of Skywalker Sound. As he tells StarWars.com, picture editors Ben Burtt and Paul Martin Smith had spent weeks with Lucas at Skywalker Ranch compiling the first rough version of Episode I. Hours long and far from the refined cut that audiences would see, it was up to Wood to review it and make notes about voices that needed recording.

“Paul and Ben ran out their sequences on video tapes for me,” Wood recalls, “and as I walked into their office, they were all stacked up really high on the table. George Lucas said, ‘Well, here you go, Matt. You’re the first person that’s going to watch the whole movie from beginning to end.’” George was obviously watching everything between the two editing rooms, but they hadn’t screened the movie in its entirety yet. This was the first output of the movie, and I had it in my hands. The Ranch has these bikes so we can ride between the buildings, and I put all the tapes in the front basket and rode back to the Tech Building.

“I got paranoid about security, not that anything could actually happen,” Wood continues, “but I sort of put something to block the door. This was the first time that someone had watched a new Star Wars movie since 1983, and I actually did call my mother and tell her what I was doing! It was several hours long with a lot of temp material. Even though I’d seen the designs and read the script, just seeing it was different. Everything was so new in this film. There was a lot to take in. There was no John Williams music and bluescreen everywhere. The movie was this new way of doing Star Wars, for sound and everything. I understood how big the project was and it lit a fire under me.”

By the time he began work on The Phantom Menace, Wood had already been with Lucasfilm for seven years, first as a tester with Lucasfilm Games when he was still a teenager, and then with Skywalker Sound. His interest in computer technology made him an ideal candidate for the team working on the SoundDroid, one of the first non-linear digital sound editing tools, which had been developed at Lucasfilm. The SoundDroid saw heavy use on the television series The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones (1992-96) and by the time of Lucasfilm’s feature production, Radioland Murders (1994), Skywalker Sound was beginning to use ProTools, another digital editor that remains an industry standard to this day.

ProTools would be used to cut sound for the new sequences in the Star Wars Special Edition, released in early 1997. It was during this period that Wood began to introduce Lucasfilm’s original sound designer, Ben Burtt, to the new digital workflow. “Film sound had been done the same way for decades, and any sort of adjustment would take a while for people to get used to,” Wood explains. “I tried to maintain that human component in teaching artists — who at that point might not have known how to use a computer at all — all of the basic steps to help them do their art with the new tools. We needed that blend. It wasn’t about just bringing a bunch of new computer people in. Ben was so eager to learn new things, and I think that’s why he took me under his wing. We had a great relationship of sharing technology and the creative process, and combining those things together.”

Initially, Burtt tasked Wood with digitizing the former’s original library of Star Wars sounds for use with a Synclavier, a digital synthesizer commonly used at the time. Burtt was not only the sound designer for The Phantom Menace, but a picture editor as well, and during that early stage he was busily shooting and cutting material for rough animatics of sequences like the podrace. Wood soon found himself fully enmeshed in the Star Wars production. “I was just pulled onto the project. There was no formal process. Once you were able to work with George and be a part of the team, you were set.

“One of the great things about developing at Skywalker Sound was that you weren’t pigeon-holed into one job,” Wood continues. “I had to know engineering, know timecode and video sync, computer programming, microphone technique, and so many other things. I learned a lot of that on the job, being in an environment where people are sharing information. Ben wore a ton of hats, and I just followed that. There was never an indication that I shouldn’t try doing new things.

“It was an absolute dream. It felt incredible to be a part of that process, but I never felt intimidated by it in the sense of ‘You shouldn’t be here.’ It was such a welcoming environment. George was a big part of that. He trusted everyone and showed his support where he could. That extended into the way we built out the team. The mindset was that we were working on an independent movie.” As Wood notes, it wasn’t until merchandise arrived from venues like Pizza Hat and Taco Bell that they remembered the global scale of the film they were working on. “You kind of lose sight of how big the movie is out in the world because you’re basically working on this independent movie with your friends. Skywalker Ranch made it feel that way. That was a funny reminder that this was going to be a big thing.”

Wood led the effort to organize Burtt’s massive collection of original sound recordings into a digital database that could be accessed at the click of a mouse, a level of access that was unusual if not unprecedented for the time. He also busied himself gathering new recordings for that very database. As Burtt had done years before, Wood took microphones into the field to capture cars, boats, planes, and animals.

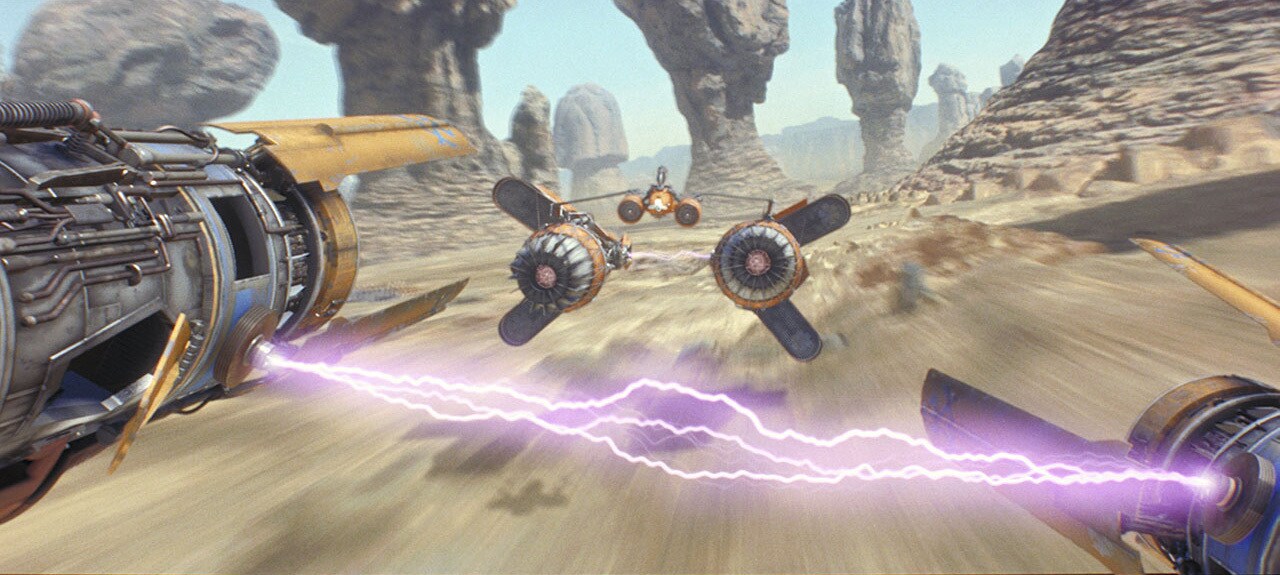

“I went up to a racetrack here in Northern California,” Wood says. “It was this kind of place where you could just sign a release, no matter what kind of car you had, and go out there and race. They gave me full access, and I got so many amazing vehicles that became parts of Anakin and Sebulba’s pods, among others. There were so many different kinds of mufflers and engines.”

Bringing his recordings back to the Ranch, he’d then catalog them for Burtt, who applied his skills at manipulating them into unique sound designs. “I was really surprised by his ability to create something with a sound that I had thought wasn’t a successful recording,” Wood recalls. “He’d make something really cool out of a piece of it. I’d sit and watch him design and layer things together. He always brought in a touch of the old Star Wars patina from the original sounds. I learned that sound is really a subconscious glue in Star Wars. Even though it looked like a completely new era, you still had lasers, ships, and lightsabers that brought you back to what you remembered Star Wars was.

“Ben gave me a great pointer when he explained that because these scenes were being cut very quickly, you only had time with your sound to establish a change point, going from one state to another,” Wood continues. “He advised me to try and find a place in the track where they’re doing something that requires a gear shift, like slowing down and speeding back up again. Try to record the vehicles at that point where you have multiple pieces to the sound. That’s what will register to the viewer. If you watch the podrace, a lot of what you’re hearing are the transitional sounds between two gears. It’s a high energy sound that happens in a very short amount of time. A steady sound doesn’t usually do that, unless it’s something like that intimidating scene when Sebulba is right behind Anakin.”

During the first year of their work on The Phantom Menace, in concurrence with the movie’s principal photography, Wood and Burtt were the only Skywalker Sound crew members on the project. As new artists joined the team, Wood remained at the heart of the project as what Burtt would call its “digital architect.”

“Tom Belfort, who was one of the supervisors on Young Indiana Jones, came on to handle the ADR spotting,” Wood explains. “Chris Scarabosio was the lead effects editor. Terry Eckton, who’d been an editor on some of the original movies, came in as an editor who primarily specialized in the droids. Gwen Whittle was editing the dialogue, and she continues to be an amazing force in the industry. Kevin Sellers was an assistant, and like me, he’d come from a technical background. He was involved in the prototypes of a lot of the programs that are standard now. Ben was the lead designer and it was very much his show.”

Among Wood’s later responsibilities on the film was capturing automated dialogue replacement (ADR) with the cast in order to refine performances in specific scenes. A one-man operation, Wood had his hands full.

Traditionally, ADR was an analog process with sound recorded on magnetic tape and the movie’s visuals played for reference on film or video tape. “You’d go into a little studio and run your lines on a loop,” Wood explains. “It was time consuming with how you’d have to go back and loop things. I had worked on Young Indiana Jones and done a few things to create digital ADR at the Ranch, but we didn’t have many of the actors in Northern California. I thought it’d be cool to come up with something portable.”

Wood partnered with Mark Gilbert and Vanessa Jane Hall of Gallery Software in London to create a streamlined, digital ADR system that he could take anywhere on his own. From Apple Computer he received a prototype G3 Notebook that could run the essential ProTools software. What usually took an entire studio to equip could fit into a few suitcases. After Wood demonstrated the system to George Lucas, the director said, “Let’s go do our ADR somewhere fun.” They ended up in the Bahamas.

Before heading to the tropics, however, they went back to London where principal photography had been centered, and where a number of the film’s actors were based. “I brought it to an actual ADR studio in case the system broke,” Wood says. “I went to Mark Gilbert’s house the night before and we were trying to fix this one significant bug. We fixed it maybe five hours before I needed to record Liam Neeson. We used the portable system there in the ADR studio and it worked perfectly.”

While still in London, the crew ultimately used Gilbert and Hall’s own home as their makeshift studio with the portable system. “It was a really nice house and we just outfitted one of their bedrooms, and everyone would come there,” says Wood. “It was very casual. I had a little closed-circuit TV and we’d set it up to do ADR. [Jar Jar Binks actor] Ahmed Best would often show up early, and I’d usually be a little stressed because it was all on me at that point to make the technology work. There was no back-up. He’d be very calm and say things like, ‘You got this, man. You’re the perfect guy for the job.’ He was such a lovely man to work with.”

In the Bahamas, Wood chose a local music studio, Compass Point, as their recording location. “We spent a week or two there, and flew everybody in. Samuel L. Jackson got to play golf. Everyone was happy and in a fun mood. George gave me some nice kudos that I’ll remember forever. He told me that it was working very smoothly and he was happy that we’d taken the risk to do it.

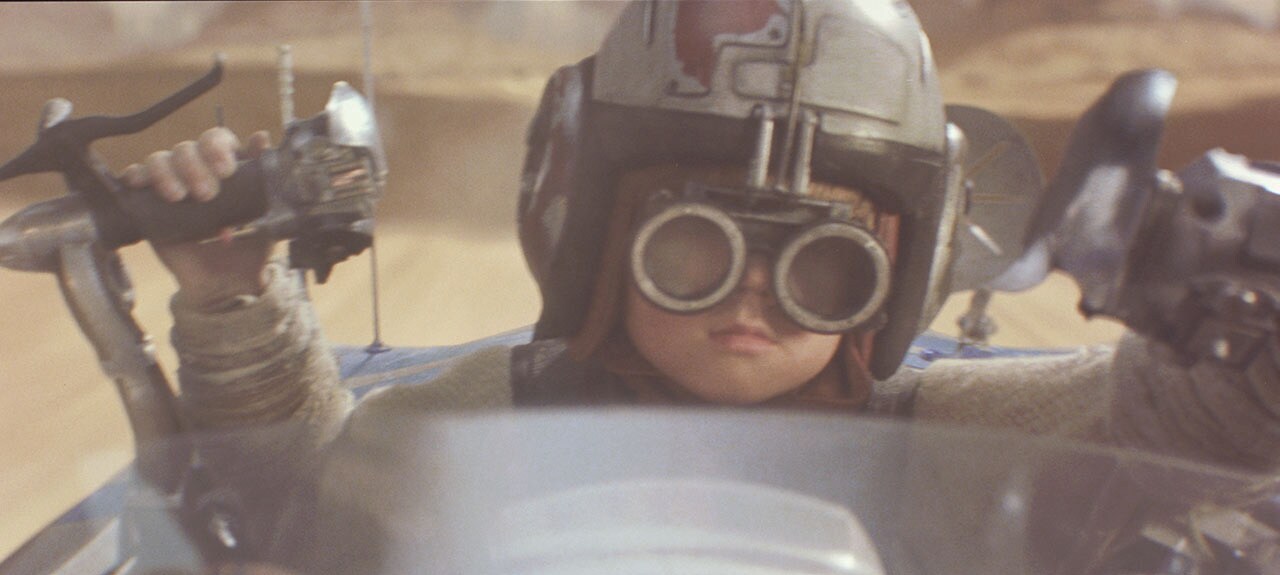

“For Jake Lloyd, I went really out there and got an early prototype of VR goggles,” Wood continues. “They were tiny little TV screens, maybe 640x480 resolution for each eye, and I was able to get this company to let me use them. I’d place them on Jake for his ADR, and he would actually see the scene happening as we looped it rather than watching the normal television. I had it as an option for any actor that wanted to use it. Some people don’t want to see everything around them while they’re recording. They’d rather be immersed in the movie. I could use my Apple laptop and output the video from ProTools into these goggles. No one was doing that at the time. Liam Neeson used it a couple of times. Jake wanted to use it all the time. He was a sweet kid with lots of energy.”

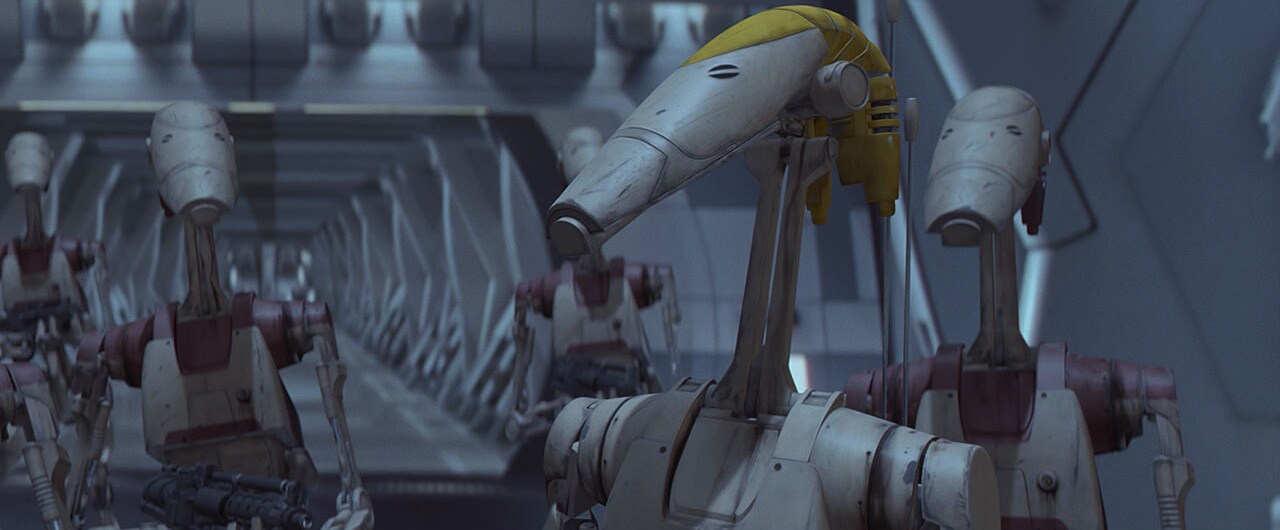

Among the seemingly countless tasks involving voices in The Phantom Menace were the many Trade Federation battle droids. During the shoot, actors stood in for the all-digital characters, and at times, Wood was able to adapt those recordings into the film, running the sounds through a program to give them a digital, robotic monotone. But during post-production, new dialogue would be written, and Wood and Burtt found themselves recording the battle droid voices themselves.

“One of the goofier droid voices is the one that says, ‘You’re under arrest.’ That’s Ben,” says Wood, who confirms that the first instance of a droid saying “Roger, roger” was also Burtt. “Starting around Attack of the Clones, I started using my voice more and more. George had this idea that, after The Phantom Menace when the droid control ships are shut down and they’re no longer connected to them, the new version of the droids are autonomous ones that require their own CPU! They couldn’t afford to stamp out a million high-quality ones, so they use these cheap versions that are goofier. By Episode III and into The Clone Wars, I’ve done every battle droid’s voice. Ben and I both have that nasally, kind of happy voice, and I still use Ben as an inspiration.”

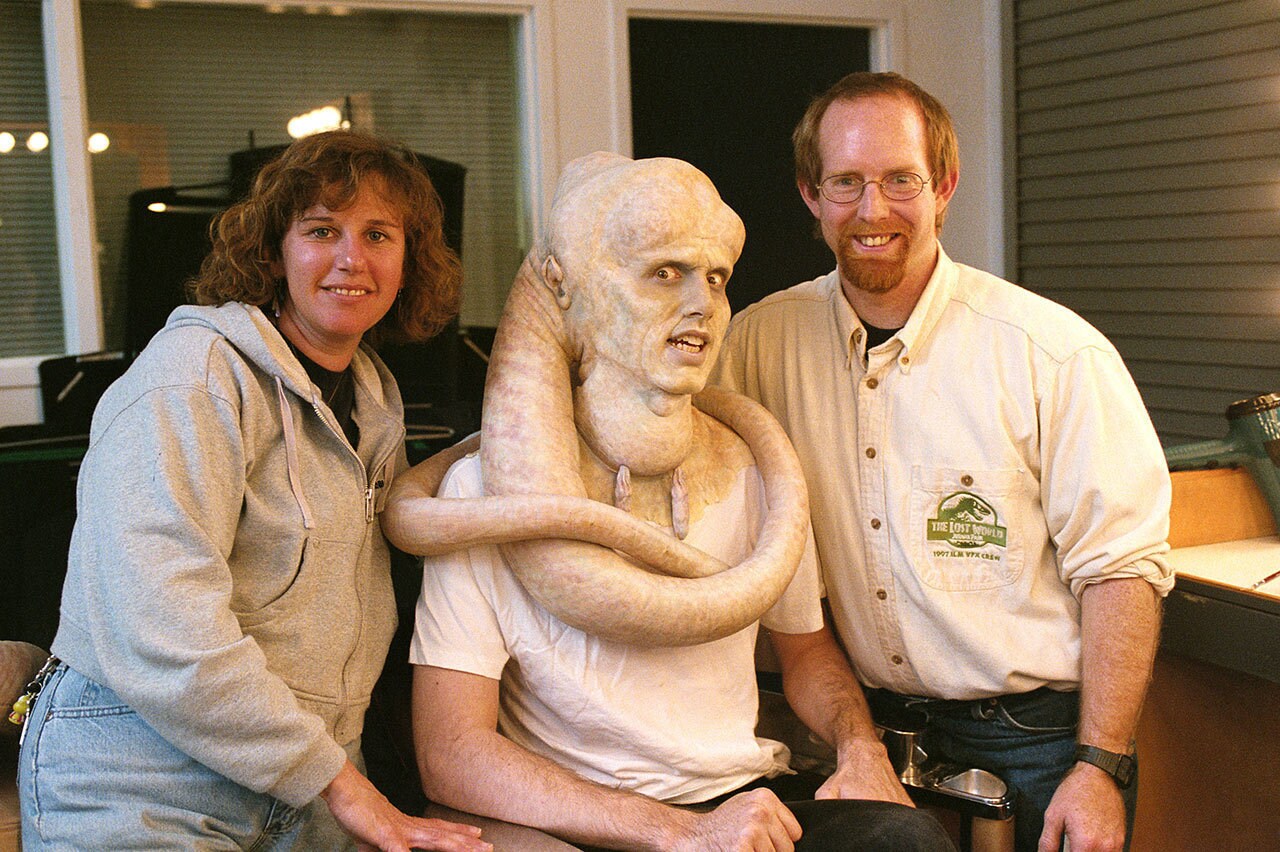

Wood’s adventures in performing characters in The Phantom Menace didn’t end with his voice, but included an appearance before the cameras as well. “I was right out of high school when I first got the Lucasfilm job, and I had enjoyed doing acting and singing,” he explains. “George knew that I liked doing performances. So, I was in the Main House one day, and [casting director] Robin Gurland was there. They had shot some other sequence with Bib Fortuna in it, but they decided to put him in the podrace stand with Jabba instead. Robin was thinking about who they should get to play him. They’d already created the three main pieces for his makeup. I was standing there taking notes for sound, but they kept looking at me, and finally George said, ‘You know, you’re kind of creepy over there lurking in the doorway. You should come in the office.’ I said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t want to bother you.’ And Robin said, ‘There’s your Bib Fortuna right there!’ I was skinny and had similar facial features as the person who’d been fitted for the makeup.”

Before long, Wood was at Industrial Light & Magic’s facility in nearby San Rafael, where he was fitted into costume and make-up. Visual effects supervisor John Knoll directed the shoot on a small blue-screen stage. “I had seen the material in the editing bay,” Wood recalls. “Jabba the Hutt was a light stand that I’d poke at to wake him up. At first, I was trying to play him like [original Return of the Jedi actor] Michael Carter did with his eyes and his teeth, and then they explained that they were going for a more serious Bib on this one. I was just shot as an element.”

As Wood’s 30-plus-year journey at Skywalker Sound continues (including five Oscar nominations and counting), he looks back on The Phantom Menace as “my favorite film that I’ve ever worked on, and I’ve worked on a lot of films,” as he says. “It was the best experience because of the blend of everything: the technology, the crew, the schedule, the location, the trust between everyone, all of it. I was also young and I had a field promotion into my first big supervising job. I get emotional even thinking about it.

“There was a lot of trust between George and the sound team, in terms of what we were making for him,” Wood says. “He never really micro-managed our artistic choices. He’d give us notes about the story and how he wanted sound to drive it. That level of trust is very rare. Because we’d been working on everything from the earliest stages, by the time we got to the final mix, there wasn’t a need to unwrap everything for him or start things over. There was this steady progression of work for two years beginning in 1997. We never did overtime because George valued family and people’s lives outside of work.”

A more recent memory forms a memorable cap on Wood’s feelings about The Phantom Menace. In 2019, fans gathered in Chicago for Star Wars Celebration, where a special panel of cast and crew convened to celebrate the movie’s then 20th anniversary.

“Going onstage with all my colleagues and experiencing the fans’ love for the movie, especially the way they received Ahmed [Best], was so heartfelt,” Wood concludes. “I was crying. It was such a joyous time for me working on that movie. It felt so nice to feel that way again. Back when it was released, a lot of people had their own feelings about what Star Wars should be and there was a generational change going on. Now, 25 years later, it’s wonderful to see people loving the prequels, especially those who grew up with them. I’ve never wavered in terms of how great the experience was of working on them. It was so enriching. A highlight of my life.”