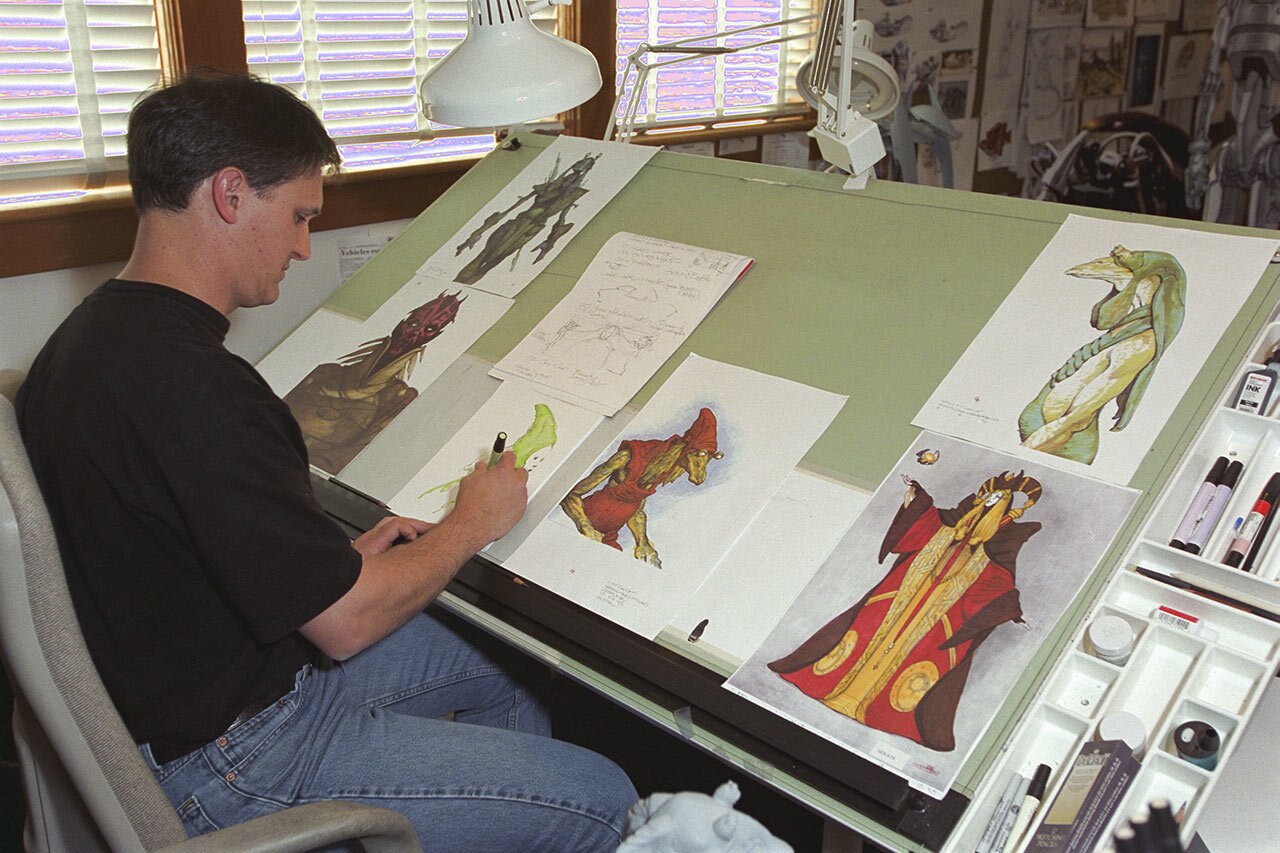

Concept and storyboard artist Iain McCaig was among the first to join Episode I’s art department and played a central role in designing many iconic characters.

In 1995, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) was still two years from starting principal photography and four years from release, but Lucasfilm’s art department at Skywalker Ranch was well underway creating designs and concepts for the innumerable characters, locations, and vehicles in the film. This included a new villain: Darth Maul.

“George [Lucas] just came up and said, ‘Darth Maul, he’s our new Sith Lord,’ and he walked away,” recalls artist Iain McCaig, who by that point had been working primarily on hero characters. “I didn’t know if Maul was male or female, an alien, anything. It freaked me out at the beginning that I didn’t get much direction. Then I realized that maybe he picked me because he liked my work and wanted me to show him what I thought a Darth Maul might look like. George clearly enjoys reacting to visuals. One of his many skills is that he can look at fifty things, make choices, move things around, take a head from this character and put it on the body of that one over there, and suddenly, it’s Star Wars. We learned to trust him and also to trust ourselves.”

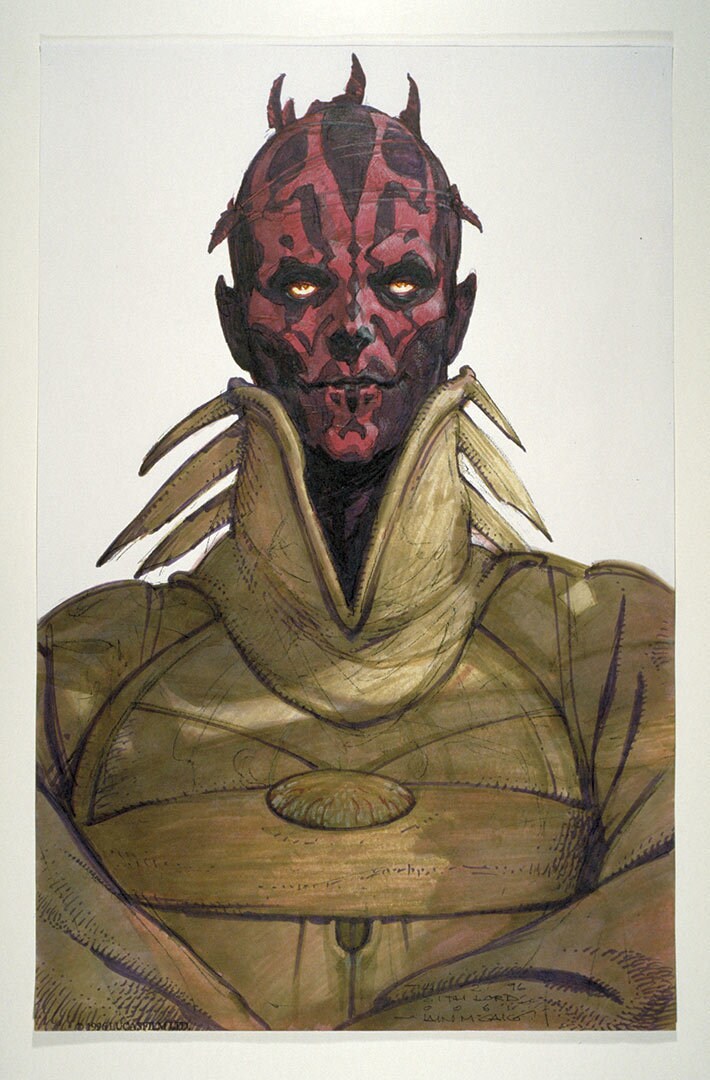

McCaig leapt bravely into the void in an attempt to find Maul’s appearance. “Darth Vader was the only Sith Lord we knew back then, so I assumed he would be wearing some kind of helmet,” he explains. “Months of trying to out-helmet Darth Vader went absolutely nowhere.” So McCaig took the helmet off, exploring what might lie underneath. “I thought maybe there'd be some kind of implanted circuitry, something to connect flesh to mask.”

Using his art department colleagues as models, McCaig experimented with a number of designs. “For [previs supervisor] David Dozoretz, I literally put a circuit board on his face. By the time I got to our production designer, Gavin Bocquet, I had simplified the circuitry to tattoos – probably channeling Rorschach from The Watchmen – and suddenly the design started to work.”

By then, McCaig had run out of models, so he used his own face. Serendipitously, George Lucas then delivered his first draft of the screenplay, describing Darth Maul as “a vision from your worst nightmare.” McCaig knew that nightmare all too well. “Working late at night in my studio, I had the eerie feeling I was being watched. My imagination conjured a dead white face pressed against the studio window, glittering eyes staring at me. It grinned sharp metal teeth as it peered, distorted through rivulets of rain. So I drew that face for George, put it in a folder and slid it across to him at the next meeting. He took one look, shrieked, and slapped it closed again. ‘Give me your second worst nightmare,’ he said.

“Don't get me wrong,” McCaig quickly adds. “I love clowns. But something about those painted expressions scares me, because who knows what they’re really thinking? So I used the markings on Maul's face to conjure contradictory emotions: malice, but delight; scowling, but grinning like a skull. Every single mark matters. [Actor] Ray Park picked up on that when asked at the first Celebration how he managed to play such a master of evil. ‘Darth Maul’s not evil,’ he said, ‘he’s cheeky.’ You can see that in the iconic scene where he confronts Obi Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn. Two Jedi, both bigger than him, and Maul looks like he's just won the lottery. He doesn't give a fig about the Trade Federation. He just wants to kick some Jedi ass.”

"I was so certain that design was a bullseye,” McCaig recalls. “So I realized I must be aiming at the wrong target. Of course, it's obvious in hindsight. Star Wars takes place a long, long time ago. That makes it a mythological nightmare, not an undead serial killer. And boy did I know my worst mythological nightmare. Ever since I saw his white painted face leering at me from an L.A. billboard when I was two years old, I've been terrified of Bozo the Clown."

As for those devilish horns, former Lucasfilm researcher Jonathan Bresman notes in The Art of Episode I that McCaig originally intended them to be feathers. They were “attached by coils of wire which cut into the flesh,” Bresman said. “Black feathers that added a touch of beauty to the face, lending an element of seduction to the dark side.” More than two decades removed, it’s evident that McCaig’s creation has come as close as any Star Wars villain ever has to the iconic Darth Vader, becoming the face of The Phantom Menace’s theatrical, marketing, and licensing campaigns, and remaining as the symbol of the film to this day.

Ironically, McCaig made an attempt after the approved design to re-imagine Darth Maul as a woman. He submitted a black-and-white-faced Sith Witch in a flayed red costume. Lucas liked the design but rejected it for Maul. Years later, he and Dave Filoni brought her to life in Star Wars: The Clone Wars as Mother Talzin, Darth Maul's mother.

One of the older, more experienced artists in the film’s art department, McCaig drew on years of work as an animator and freelance illustrator, creating art for book and record covers. His portfolio included everything from Jethro Tull's “Broadsword and the Beast” album to Ian Livingstone's Fighting Fantasy choose-your-own-adventure game books to illustrations for fantasy classics like The Hobbit and Peter Pan. He was exhibiting his Pan art as Guest of Honor at an event in San Jose, California when Lucasfilm recruited him, eventually joining Industrial Light & Magic and drawing 2,500 storyboards for Steven Spielberg’s Hook (1991).

Before ILM, McCaig worked briefly for Lucasfilm Games, re-illustrating the close-up cut-scenes for The Secret of Monkey Island (1990). “They only had a handful of colors for the first version, but now – wow! – there were 256 colors,” he recalls. “It was the first time I'd ever used a computer, and this was long before Wacom tablets and digital pencils. I ended up knitting the pictures on the screen – with a mouse.”

McCaig's first project at ILM was on Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), working with a talented young art director, Doug Chiang. When Chiang eventually left ILM to head up George Lucas' new Phantom Menace art department, he suggested McCaig – now a seasoned freelancer in the film industry – submit his portfolio. “I sent Doug my portfolio like everyone else,” he notes, “and was thrilled when he invited me to join him and Terryl Whitlatch in George's personal art department, JAK Films. JAK stands for ‘Jett, Amanda, and Katie,’ George's kids, by the way, not, as some wags would have it, what he paid us.”

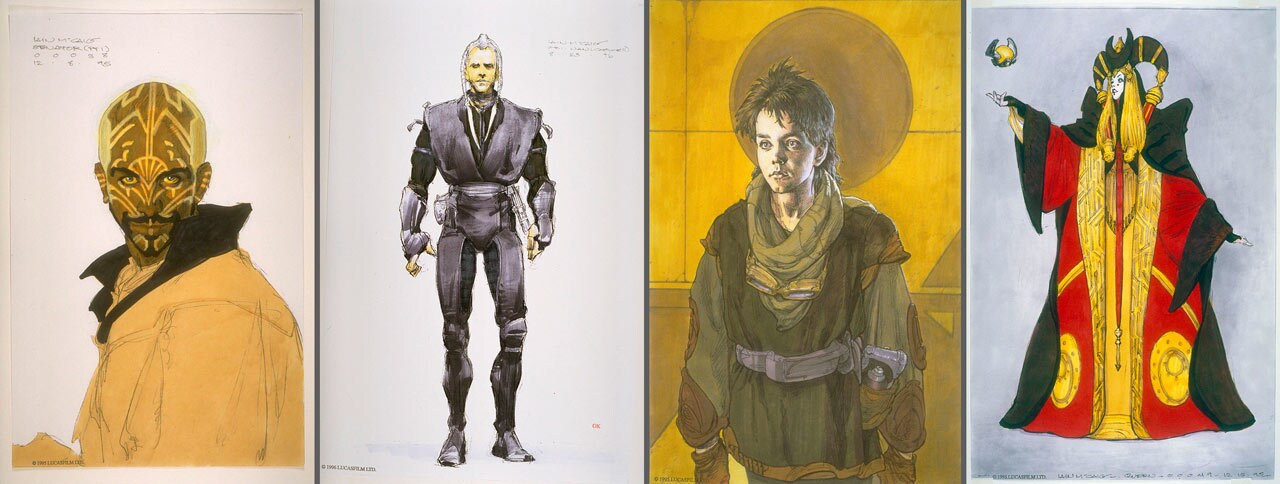

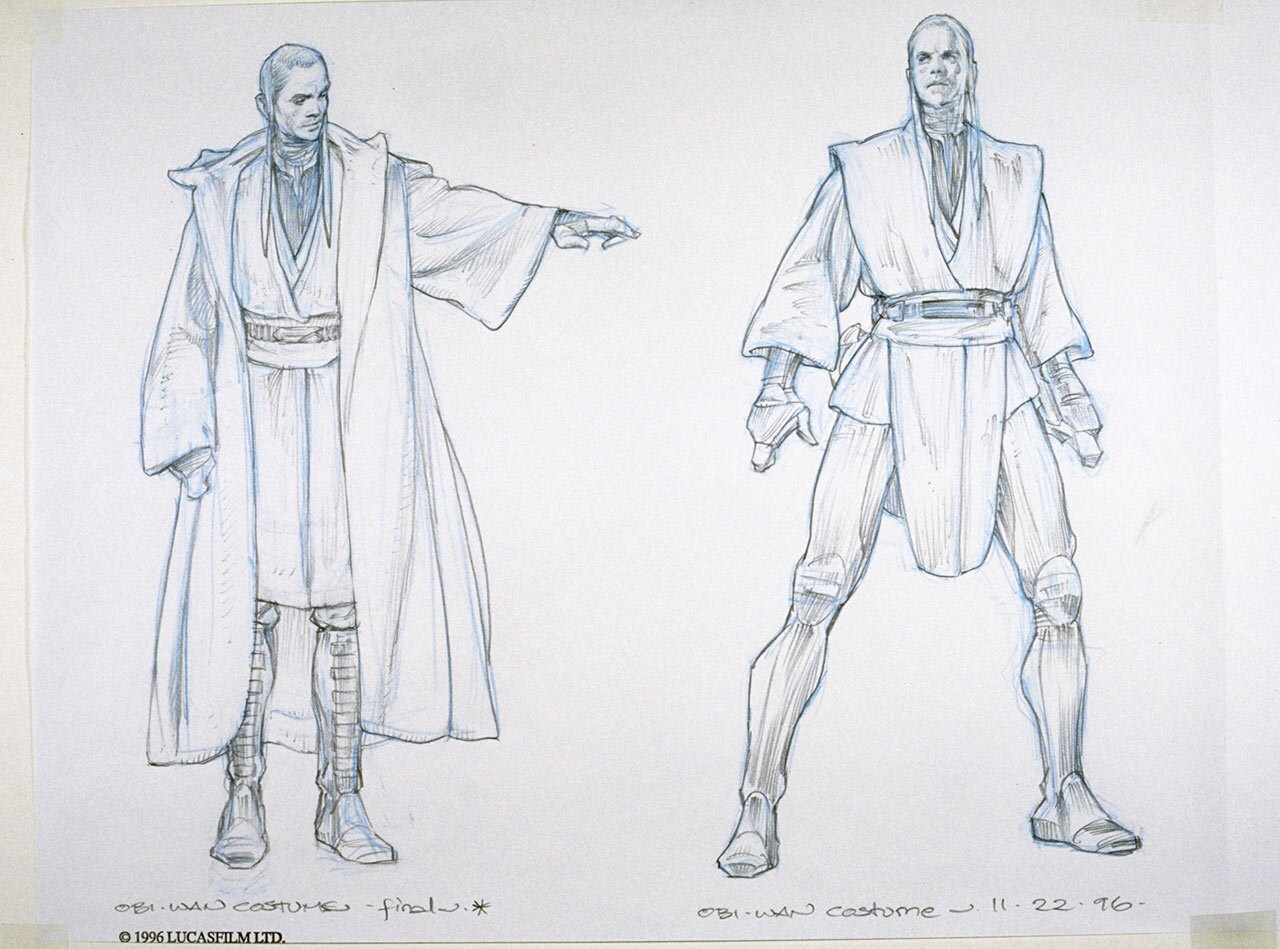

“Doug and Terryl had already been working there for a year,” McCaig continues, “and they'd already covered the walls with creatures and spaceships and droids and alien landscapes of every description and I thought, man, what am I supposed to do? Then I realized there weren’t many drawings of people, and to me, people are the best fantasy creatures ever. So I ended up taking on most of the main characters: Obi-Wan, Padmé, Qui-Gon, and Anakin, as well as Yoda and the Jedi Council, the senators and various scum and villainy. I took the first pass at designing their costumes too.” Eventually, the team grew to include Jay Shuster, Kurt Kaufman, and an entire group of storyboard artists, which Chiang and McCaig oversaw.

As George Lucas worked on the first draft of his screenplay, he would visit the artists weekly and share a new installment of the developing saga. “George would lean back in his chair, half close his eyes, and tell us the next part like it was a bedtime story,” says McCaig. “He'd always stop when we were dying to know what happens next, then get up and walk back downstairs, leaving us with this new nugget of story.”

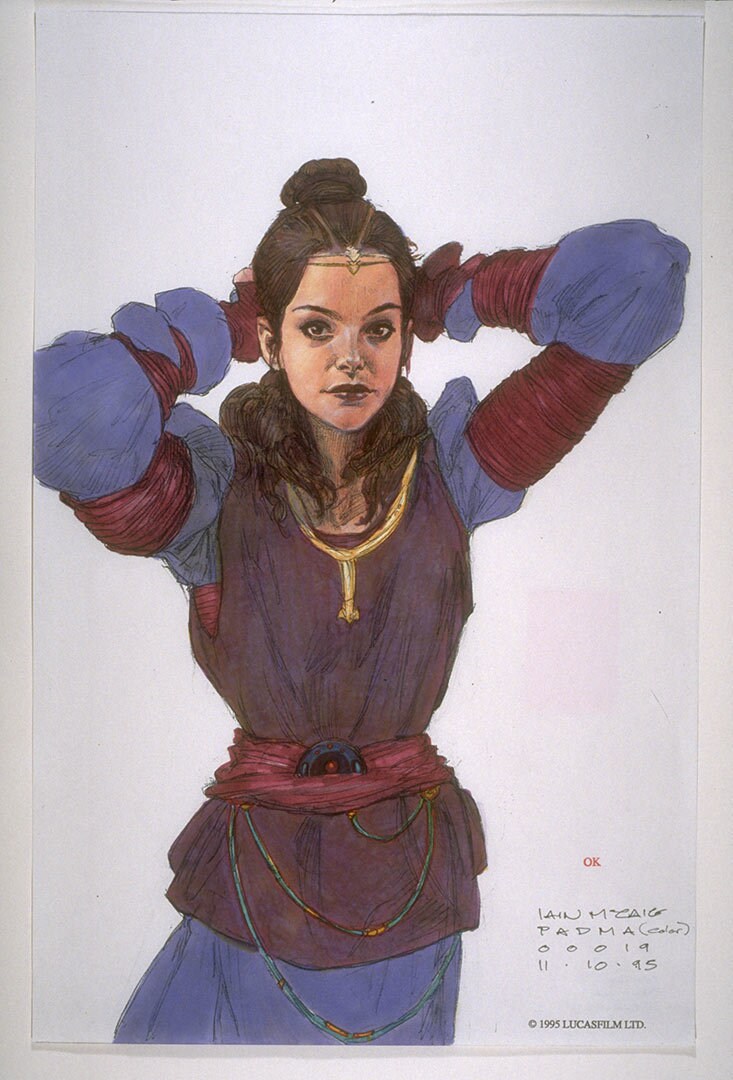

The first character McCaig tackled was the young Queen of Naboo, Padmé Amidala. "She was the Force of nature trying to hold back a tide of evil, so I wanted her to be the first flag in the ground, a clear statement against which the other designs are measured.” To do that, he needed to understand the philosophy behind a character’s appearance and the deeper motivations that inform it. “If it’s called Star Wars,” McCaig says, “then what are the characters fighting for? What is the good that they are trying to protect, and why do we want them to succeed?

“George often said that it was a battle between organic lifeforms and machines,” he explains. “It’s not that the machines are bad, but they tend to steamroll over the soft, squishy organic things. Also, the squishy things misbehave a lot, creating conflicts. At the heart of it all is a Queen trying to hold everything together without going to war, and the Jedi doing their best to help her.”

Lucas mentioned being inspired by Princess Ozma from L. Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz. “At the same time,” McCaig says, “he challenged us with the question, ‘What makes Star Wars Star Wars?’ When he made his first trilogy, he said, there weren't many other films like it. Now there's Star Trek and Blade Runner and Alien and a host of others. What, indeed, is a Star Wars movie? And how do we shift the Star Wars you know into a whole new time period?

“The through-line came from looking at history,” McCaig continues. “If you go back a hundred or so years in our time, you hit the Victorian era, the time right on the cusp of industrialization, when most things were still handmade. An inventor would be proud of what they did; like an artist they'd often put a little plaque with their name on the machine, as if to say I made that. Maybe going back one hundred years doesn't necessarily mean things are simpler. Instead, they might be more ornate and artistic, reveling in being hand-made. You don’t just buy a costume off the rack. It’s made for you.”

With the help of Jo Donaldson and her team in the Lucasfilm Research Library, as well as “freelance-researcher-extraordinaire” David Craig, McCaig plundered the Art Nouveau style of the early 20th century, developing an approach for the Queen and Naboo culture in general, which he dubbed “Space Nouveau.” He was also able to tap into the historic Paramount Studios research library, which George Lucas had acquired a decade earlier. McCaig also went outside at Skywalker Ranch, drawing plants, trees, whole forests, absorbing anything and everything organic.

“George loves illustrators,” says McCaig, “Fine artists create to satisfy themselves, but illustrators create to tell stories, and those stories reflect the time they live in, encapsulating a piece of history.”

To help create a historical sensibility that felt distinctly Star Wars, McCaig tried to ensure that each design pulled inspiration from elements in three different locations around the world, or three different time periods, or a combination of both. “If it’s reappearing in these different places and different times, chances are it's an iconic archetype – something that's part of our collective unconscious.” Queen Amidala's white face paint, for example, could be found in Japanese Geishas, the traditional appearance of married women in Mongolia, as well as England’s Queen Elizabeth I.

From the Queen, McCaig turned to the Jedi, Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi, who together experienced a fairly significant story change. “It’s interesting how things evolve,” McCaig notes. “For a time, the older Jedi was named Obi-Wan and the younger Jedi was named Qui-Gon. It was very poignant that at the end, as Obi-Wan dies and Qui-Gon defeats Darth Maul and stays with his Master as he passes away, he not only takes on his Master’s quest, but he takes on his name. Qui-Gon becomes Obi-Wan. That’s why when you see Alec Guinness in A New Hope, he puts his hood down and goes, ‘Obi-Wan? Now that’s a name I’ve not heard….’ Because he’s not Obi-Wan, he’s Qui-Gon. And right at the end, George changed it.”

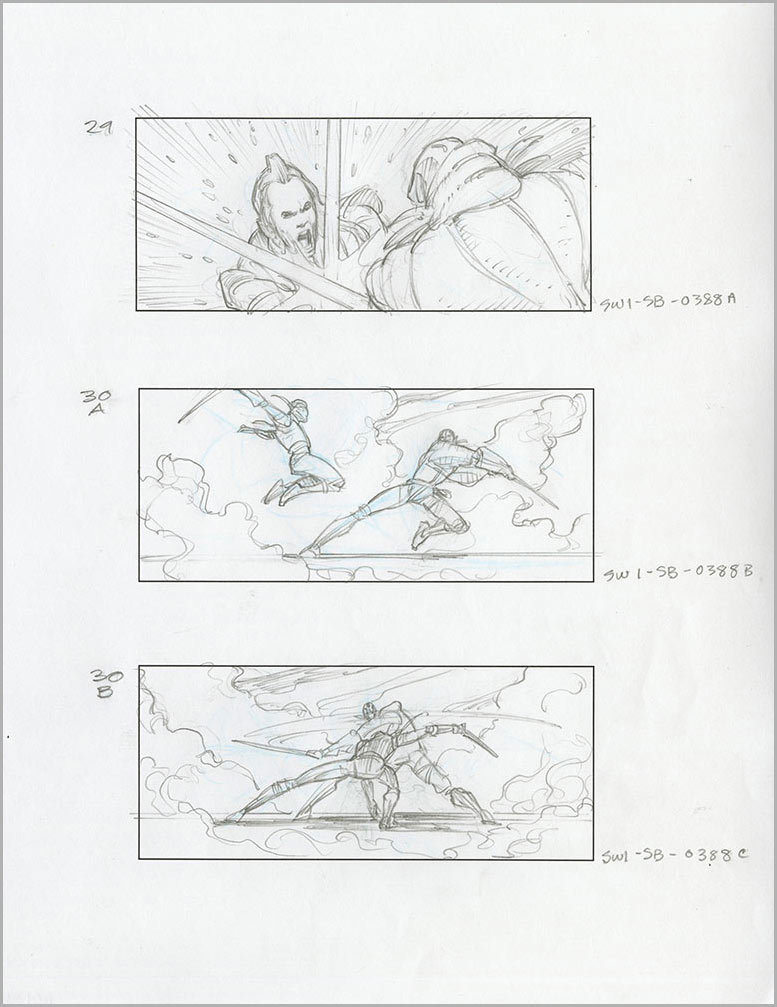

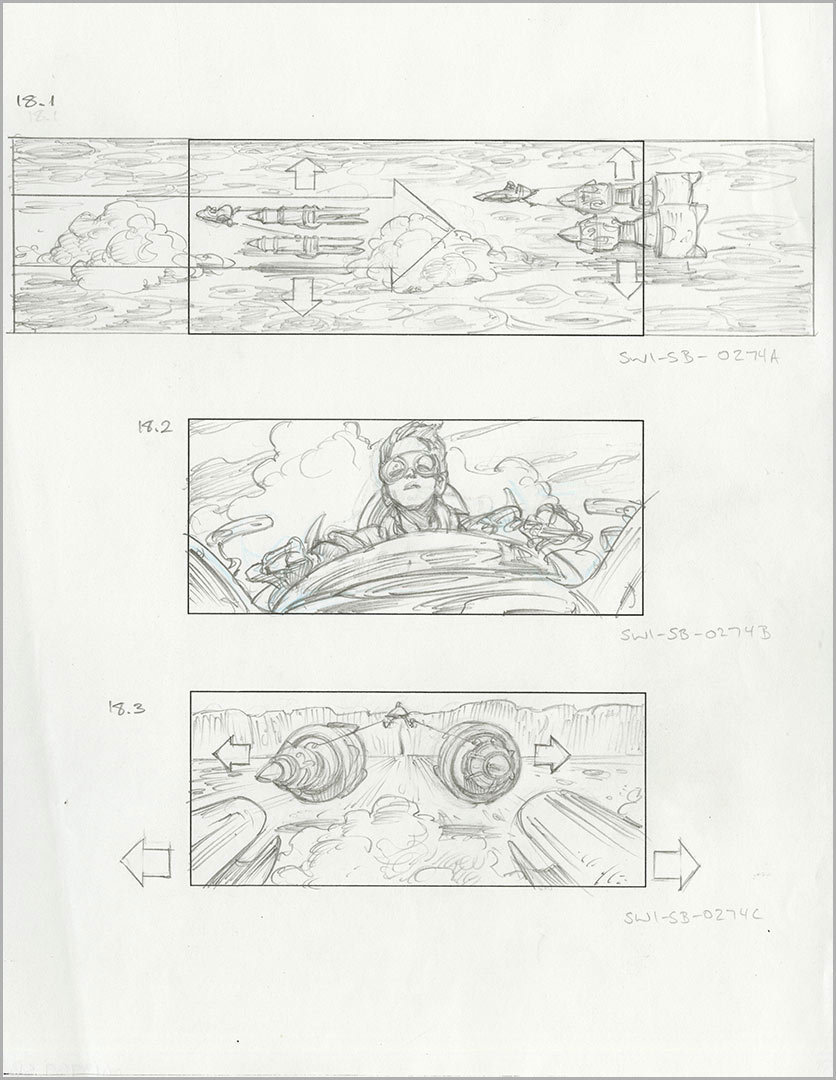

McCaig not only designed most of the characters, but storyboarded several sequences as well, a Star Wars tradition going back to Joe Johnston, who did both for the original trilogy. Typically, as McCaig notes, George Lucas might give a precise direction or two for a given scene, but mostly left the artists to imagine it for themselves and show him how they thought it could work.

“There is a difference between an illustration and a storyboard,” McCaig explains, “In an illustration, the viewers can linger on and explore the image at their leisure. With a storyboard, the viewers have a set amount of time to process an image before they're moved into the next frame, and in the normal course of things they don’t get to go pause or go back. That’s the difference between a comic book and a storyboard as well. With storyboards, you control the flow of time.”

Among other sequences, McCaig boarded one of Darth Maul’s first appearances, a surprise attack on Qui-Gon and Anakin on Tatooine. As he recalls, George Lucas wanted it to be “like a cockfight, very fast and dangerous.” Two Force-using warriors in their prime had never been seen in battle before in Star Wars. McCaig studied martial arts films and used all the storyboard tricks he'd learned over the years, and soon presented this initial duel to Lucas.

“I put all my boards on the wall and was rather proud of the result,” he recalls. “Then George arrived, and, as usual, looked at it quietly. After a while he said, ‘So Iain, what were you trying to do here?’ ‘You said make it fast,’ I told him, a little deflated. He laughed. ‘Fast? I’ll show you fast.’ He went to the board, ripped ten drawings off the wall, re-ordered three or four of them, and suddenly it was a zillion times faster. ‘Always follow the action,’ he said, leaving me with a smile and a pearl of wisdom that has followed me for 30 years.”

McCaig is keen to note that it was “the best training in the world” watching Lucas respond to everyone’s work and develop ideas from it. “But he’d always let you try and do what you wanted first. I've never met a director who empowered and trusted artists as much as George.”

That doesn't mean that Lucas didn't have very specific requests sometimes. “I remember he wanted a very specific race car to be the inspiration for the pod on Anakin’s podracer – a Birdcage Maserati,” McCaig continues. “Doug Chiang and Jay Schuster were working on it, but George wasn't seeing what he wanted yet. Finally, he pulled a piece of paper towards him, and in perfect three-point perspective, he drew the car! I looked at my colleagues and we all had the same thought, ‘Whoa, George Lucas can draw?!’”

As he looks back, McCaig has an unusual mix of feelings about the experience of contributing to the Star Wars mythos. “When I was seven, eight, nine, I was reading books like Dune and Something Wicked This Way Comes,” he explains. “When Star Wars came out, I was already in Art School and much more interested making art and falling in love than watching a family friendly space opera. Star Wars didn't really click for me until long after I started working on it. American Graffiti, on the other hand – now that was my film!”

It was actually when he started traveling to give talks at Star Wars exhibitions that McCaig experienced firsthand just how much Star Wars has touched audiences around the world. “I like to teach people to draw and tell stories, and many barriers disappeared because folks knew I'd worked on Star Wars.” But while his respect for Star Wars grew, it still didn’t connect for him personally. “It was Andor that finally caught my heart and soul. Gone were the superheroes and for the first time I felt how fragile and terrible it was to live in the time of the Empire, and how some people persevere despite everything, no matter the cost. That connected Star Wars to the real world for me and I fell in love with it. Now, I see endless untouched possibilities for this saga, and I would love to be part of creating them.”

These days, McCaig is a storyteller across many different mediums. “When I joined Lucasfilm, I also began a 30-year career as a screenwriter. Now I'm writing novels and short stories” he says, “and a musical too, believe it or not. I love having an audience that I can actually see and hear. I think it's the antidote to 40 years of Non-Disclosure Agreements.” And would he ever consider working with Lucas again? “I believe George has retired and, if he's following through on his dream, he's happily making films just for himself,” McCaig laughs. “But yes, absolutely. He would only have to clap his hands twice and I would be there. I think we all would.”