The renowned visual effects supervisor takes us inside some of Episode I’s most groundbreaking visuals.

Kicking off the highly-anticipated prequel trilogy, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace arrived May 19, 1999. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Phantom at 25,” a special series of interviews, editorials, and more.

To put it simply, there is no Star Wars: The Phantom Menace without John Knoll.

Having joined Industrial Light & Magic in 1986 as a technical assistant, Knoll cut his teeth and worked his way up on projects ranging from Captain EO to The Abyss, but the turning point in his career came with the Star Wars Special Editions. Working directly with George Lucas, he served as visual effects supervisor on new, digital additions to the classic films.

Though he actually started as a model maker, Knoll embraced digital visual effects early — he’s a co-creator of Photoshop — and coming off the Special Editions, Lucas chose him as visual effects supervisor on The Phantom Menace, along with Dennis Muren and Scott Squires. Motion-capture, computer graphics (CG) characters, digital sets and backgrounds, you name it — The Phantom Menace would either require inventing these techniques or accomplishing them at levels never before attempted.

On a Zoom call with StarWars.com, Knoll recalls the first big meeting with Lucas for The Phantom Menace, which saw the director going over storyboards and the movie's many effects-heavy sequences. “We were used to a situation where almost every project that we work on had some aspect of it that hadn't been done before,” Knoll says. “But for Phantom Menace, almost every board that we were looking at had something that our tools couldn't currently do: whether it was things like very realistic, fully synthetic terrains, whether it was characters with clothing. All the Gungans were wearing clothing, and we didn't have a good cloth simulation tool at that point. We had dense scenes that had dozens or hundreds of characters. I think that the most complex thing with CG characters we'd done to that point was Mars Attacks, and I think there was a shot that had 18 characters in it that just about brought the whole system to its knees." The challenges Knoll now faced with The Phantom Menace were staggering. "There were all sorts of aspects, page after page, I'm writing 'em all down in a little notebook, and I filled multiple pages with things that were unsolved problems at that point. So that was a pretty eye-opening experience, just the scale of what we were going to have to do.”

As The Phantom Menace celebrates its 25th anniversary, Knoll — now ILM’s executive creative director and sr. visual effects supervisor — spoke exclusively with StarWars.com about how he and ILM pulled off some of the film’s most iconic effects.

The podrace

The action set piece of The Phantom Menace, the podrace sees young Anakin Skywalker and his competitors zoom through the canyons of Tatooine at impossibly high speeds. “One of the first images I saw was the beautiful Doug Chang painting from the podrace of the two engines on the tethers and racing over desert terrain. I loved that image and I thought it was very exciting," Knoll says. "Just reading through the description of it in the script, it seemed that this was going to be really challenging. It was exactly the kind of sequence that we're really drawn to, in that it presented a bunch of challenges that you couldn't really do with the tools that we had available at the time. And chief among them for me was generating the environments.”

Knoll saw the podracers as moving at 500 miles per hour and subsequently ruled out most traditional techniques, including shooting helicopter plates (“Helicopters can only go about a hundred, 120 miles per hour”), using models (“One of the problems was that that kind of speed, any reasonably scaled model, you would pass through it just instantly”), and matte paintings (“Matte paintings aren't good at communicating travel through an environment, and usually they're used for a fixed perspective”). Still, he had some new tricks up his sleeve.

“That really only left one possibility after you eliminate the other possibilities there, and that's, ‘Could we do it with computer graphics?’ At the time, we had never really done photorealistic CG renderings of terrain. We'd done some tricks where we'd taken matte paintings and we'd projected them onto geometry to get some perspective change, and [model maker] Paul Huston and I had been experimenting with that technique of camera projection. So I thought, ‘Well, maybe this is the way to do it.’”

As a test, Huston made some models of mushroom-shaped rocks out of foam and plaster, then painted and digitized them. After that, Huston and Knoll moved the models into the ILM parking lot, took photos of them from multiple angles, then superimposed those onto the digital version. It worked.

“That gave us something that looked like photography, because it was photography, but it could move in three dimensions. And after, I don't know, four or five weeks working on this, he had a first shot where he had a photograph of a cloudy sky as a backing. We had a simple ground plane that just had little undulations in it, zipping by with a number of these rocks. He took the same rock, replicated it a number of times, and did a shot of us flying through them. It was pretty stunning. I saw the first rendered sequence of that. It felt like something we'd never really seen before — fully synthetic terrain that had a very high level of photographic realism and the speed, most importantly, the kind of speed and control that we were going to need to do the sequence.”

The defining moment in the whole process came when Knoll showed the test footage to the Star Wars creator himself. “I talked to Paul about doing this test while we were still in pre-production, and when I got the first render of it, we'd already started shooting. So I got a little eight-millimeter videotape of Paul's test, and I popped it into a video recorder on set and played it back on one of the monitors. That was a really thrilling experience for me," he says. "It showed that, yes, this idea of doing this with, essentially, three-dimensional matte paintings was going to work. And I showed it to George, and he was very excited. That kind of was the proof that, yeah, this is all going to work.”

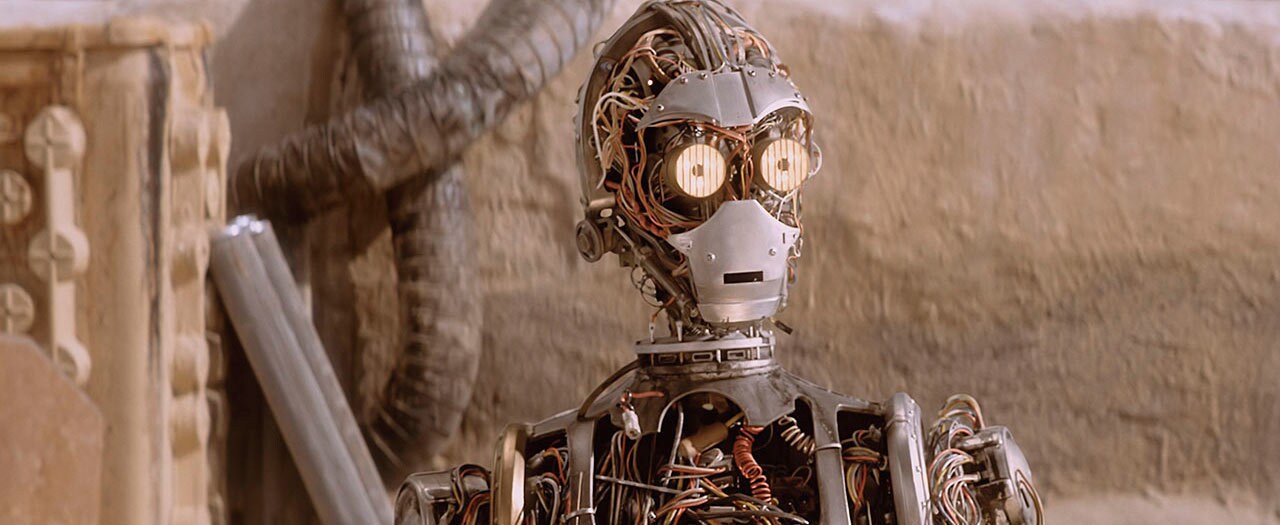

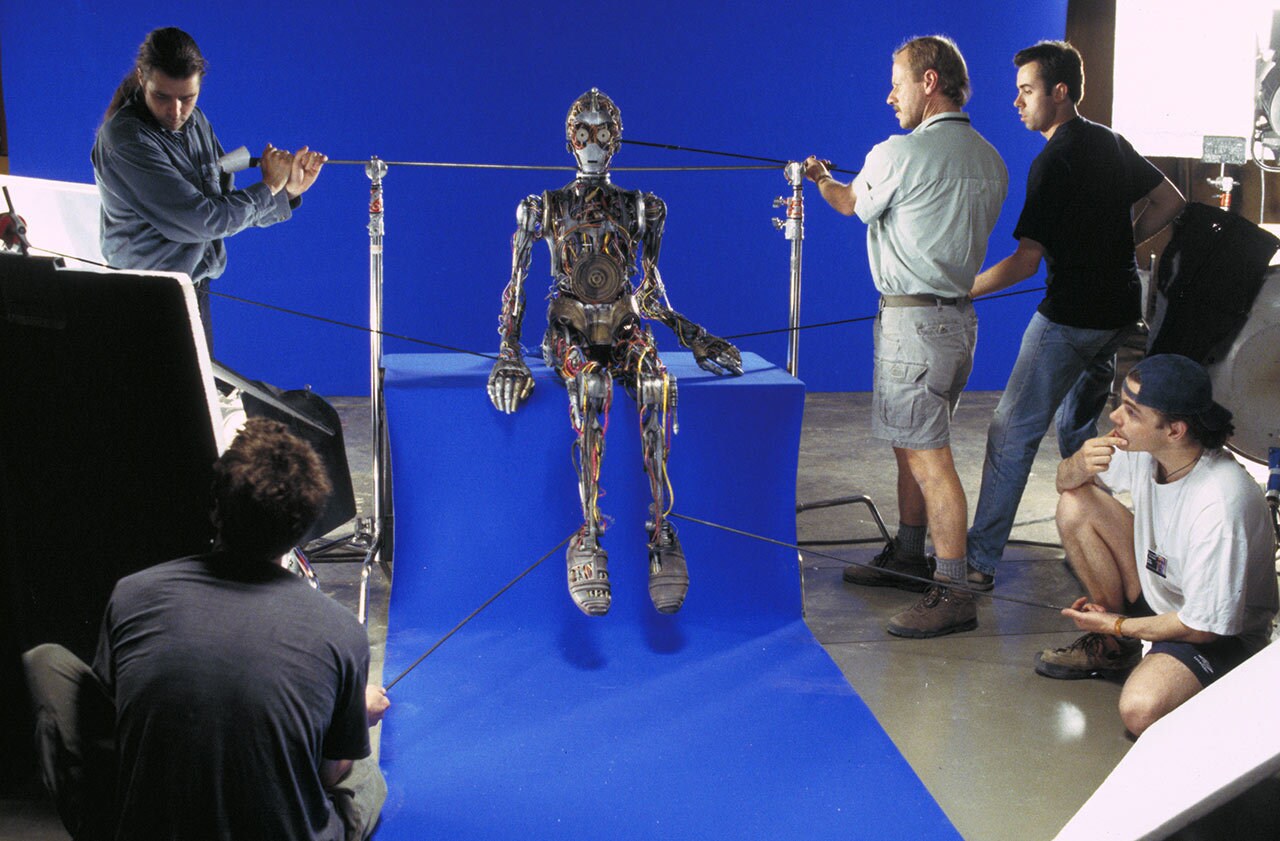

C-3PO

In The Phantom Menace, we learn that it was Anakin who built our favorite golden protocol droid, C-3PO. Except Threepio isn’t quite finished in the film, appearing in a more basic form of wires and gears, with his famous coverings yet to be added. So while Anthony Daniels had performed C-3PO in costume in the classic trilogy, there was no way a person could play the character via the original method. Knoll had to find another path.

“Seeing the artwork and seeing him in that skeletal form, my first thought was, ‘Could we do it as a full-sized puppet of some kind?’ I had just recently seen a video of some bunraku performers. This is kind of Japanese puppetry where performers in a black suit, in front of a black curtain, will have a puppet — like a skeleton or something — attached to their front, and they'll move around in a way that is very convincing and lifelike. And because they're wearing a black suit in front of a black curtain, you kind of tune out the performer and you're really just looking at the puppet. I figured we could maybe do C-3PO as some version of that.” For The Phantom Menace, the performer would be digitally removed.

Knoll approached ILM model maker Michael Lynch about crafting something they could test. Lynch created a simple form out of PVC pipe, and it seemed like a viable option. Knoll then asked him to build the real, functional prop. “He built it to his own proportion so that it would work with him driving it, and so we had him come and be C-3PO for us on set. Some of the fun moving bits, like the little gizmo that's spinning inside C-3PO's head, I think those were all Mike Lynch contributions — just cool ideas that he had and brought to the table.” Knoll feels it was a success, quirks and all.

“It worked reasonably well,” he says. “There's times when you can see that it's a little bit awkward in its motion, but there was something that was kind of charming about that that I still like a lot. That it's a real physical prop and was there on set in the real lighting helped keep the realism pretty high on it. That technique, we've kept going with that. We're still doing that on The Mandalorian. Every season, we regularly do bunraku-style puppets.”

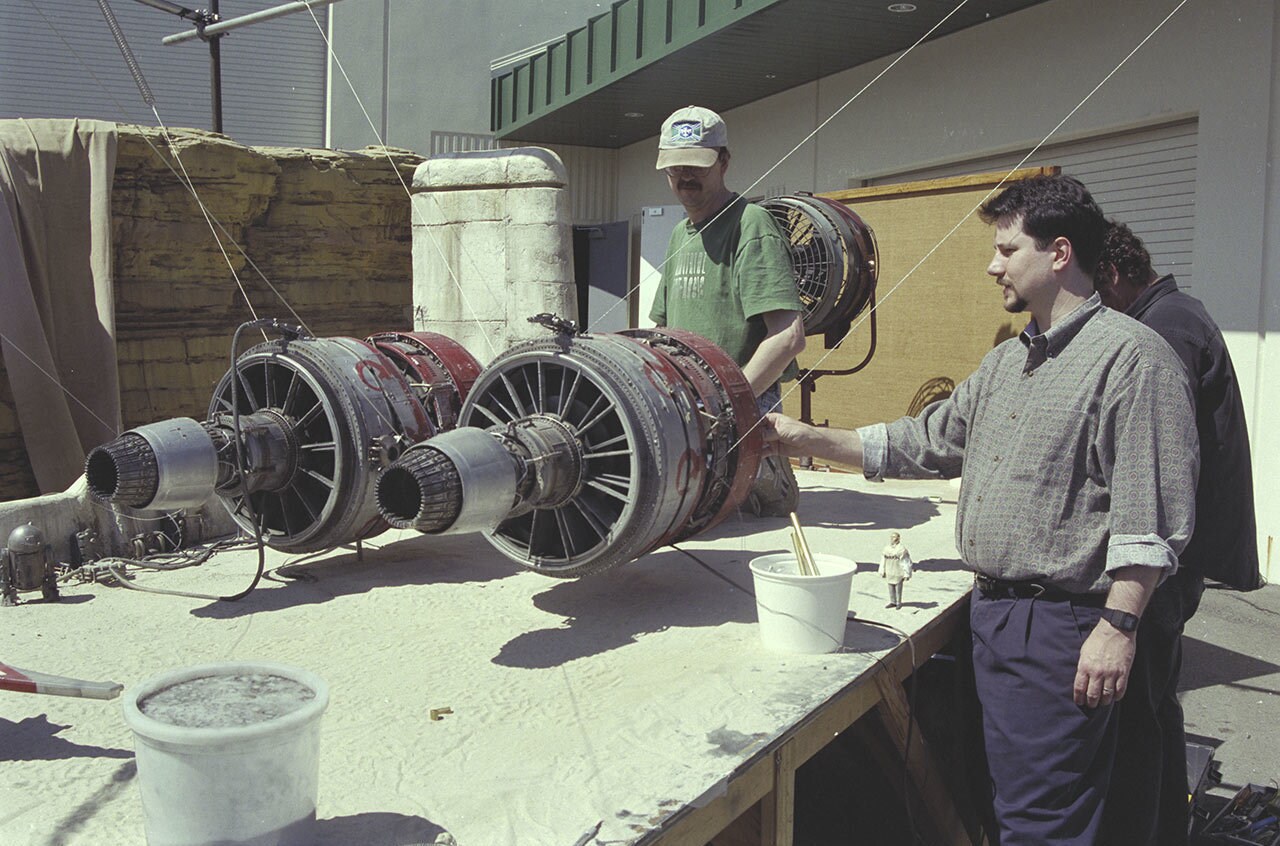

Theed

Naboo's Theed, one of the central locales of The Phantom Menace, was a city unlike any previously seen in Star Wars. Inspired by ancient Rome and classical European architecture, it was to feature ornate palaces, buildings, and squares. Despite the prominent use of digital effects in the film, Knoll felt a traditional technique was more appropriate in realizing Theed. “I had decided that Theed city made a lot of sense to do largely in miniature. So I got the model shop started building a pretty big selection of miniatures that were probably 48th scale or so, maybe a little bit bigger than that, of a whole bunch of buildings in Theed city, with the idea being that we would set them up on an outdoor tabletop and shoot them in sunlight, and get this naturalistic and realistic result,” he says. “And that is indeed what happened.”

Knoll is still enthusiastic about the results. “The models were just spectacular," he says. "I thought they were really beautifully finished. And if we’re shooting this direction and then this direction, you could take a bunch of the buildings here and you could turn 'em 90 degrees, rearrange 'em, and get what looked like a unique view, any direction you looked. The model shop did really clever things with flowers and planter boxes and that kind of stuff, coming up with really clever miniature versions of those things. I think the result was extremely realistic. I look at those shots and I feel like it's hard to know where a set piece ends and a miniature begins.”

Looking back

After The Phantom Menace, Knoll would work on the rest of the prequel trilogy, as well as blockbusters ranging from the Pirates of the Caribbean films to Avatar — even making time to dream up the idea for Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. But he credits The Phantom Menace as giving him the foundation for all of it.

“I'll always be grateful to George for that opportunity,” he says. “I felt like over the course of Episodes I, II, and III, I got a whole career's worth of experience concentrated into eight years of furious activity. The scale of what we were doing and how much R&D we had to embark on to be able to just get those films done built up a lot of confidence. I came out of that experience feeling like, ‘Nothing's ever going to phase me again.’ Complex challenges, large scope of work — we've got methodologies now that can tackle that kind of stuff, and it all seems pretty doable. I'm not afraid of big projects anymore. It's served me well since then. A lot of what I learned from George and from tackling a project of that kind of scale has been really wonderful, and I got to be a much better supervisor by virtue of having engaged with George on those projects.”