The longtime friends and colleagues, who worked for Industrial Light & Magic on the film, discuss collaborating on the rancor sequence and beyond.

Star Wars: Return of the Jedi arrived in theaters on May 25, 1983, bringing an end to the original trilogy in memorable fashion. Marking its 40th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Jedi at 40,” a series of articles celebrating the film that brought us Jabba’s palace, Ewoks, Luke Skywalker’s final confrontation with the Emperor and Darth Vader, and so much more.

The rancor looms large for a creature whose appearance on screen in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi lasts for a mere three minutes. In a scene that brings suspense, terror, and action into the dimly lit dungeon beneath Jabba the Hutt’s dais, the ravenous beast lumbers into view, crunching through a Gamorrean guard before turning its formidable and fearsome visage toward Luke Skywalker.

Roaring fully into camera with a snarling maw of jagged teeth, the rancor reaches its grimy talons toward Luke and the audience, ready for its next meal. Then with not a second to lose, Skywalker desperately grabs a skull and lobs it at the control panel that sends the door crashing down upon the beast, ending the heart-pumping battle. Jabba is outraged. The rancor keeper is in tears. And Luke Skywalker lives to fight another day.

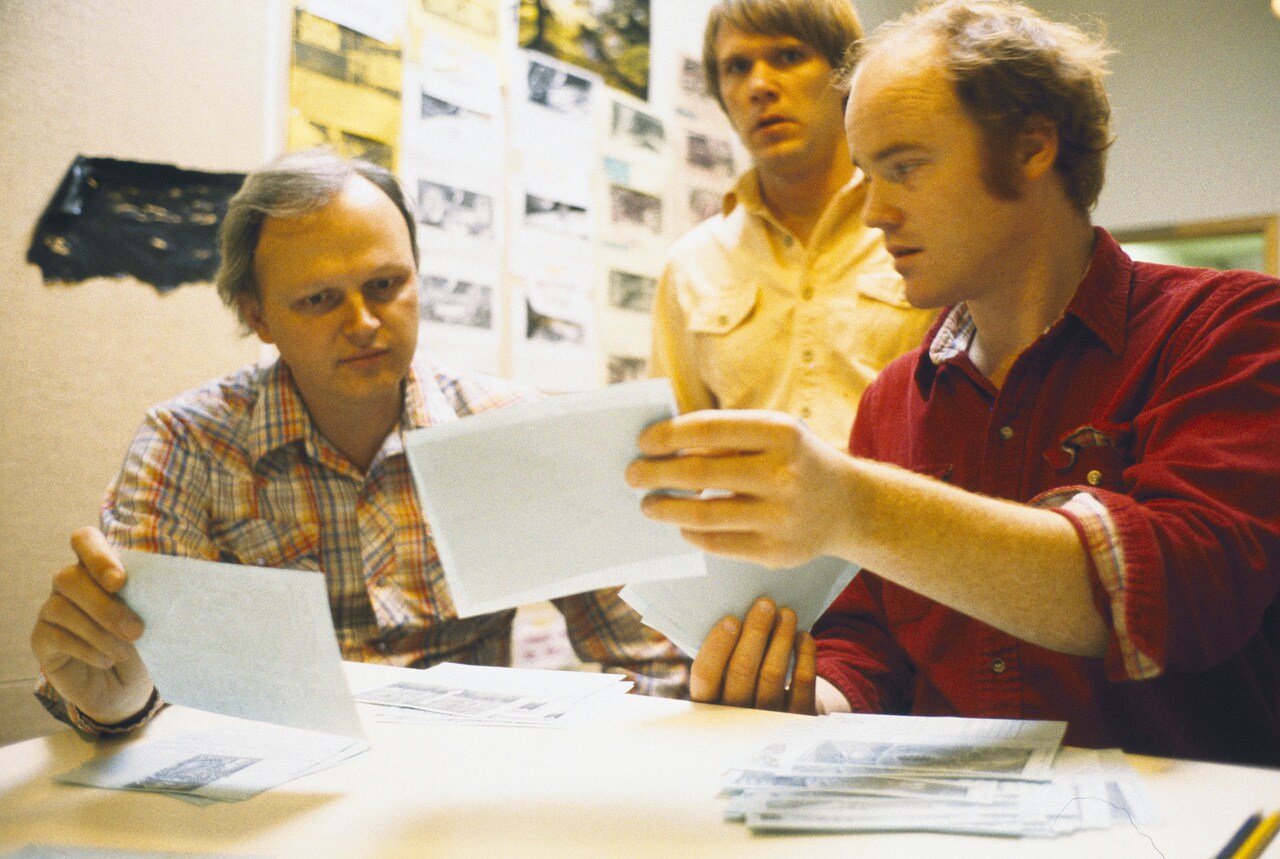

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Return of the Jedi’s debut, recently StarWars.com sat down separately with Dennis Muren and Phil Tippett, one of the VFX supervisors on the film and the head of the monster shop, respectively, to talk about their collaboration on the rancor pit, their enduring friendship, and the legacy of Star Wars.

StarWars.com: At the start of the production cycle, did Return to Jedi feel like a last hurrah of sorts?

Dennis Muren: Yeah, it sort of did. Having done Star Wars and Empire, you know, it's like “Another one?” I'd heard [George Lucas] talk about nine films or six films since around the beginning of Empire. Somewhere I heard the mention of 12 [Laughs.], but I don't know how true that was. We kind of knew there would be a third, though, after the second one. So, we were ready for it. But then after that, what?

StarWars.com: If we can go back to the beginning, do you remember where you were at in your career and in your life when you started working on Jedi?

Phil Tippett: Well, after Empire was a success, we actually overlapped a bit and went straight on to Dragonslayer. And then kind of did the same thing as we were wrapping up Dragonslayer, we went straight into Jedi.

Dennis Muren: I'd gotten married and we were thinking about having kids. We moved into a house and all that's going on. I was offered Dragonslayer, then I was offered E.T. because when [Industrial Light & Magic started] they found out there's going to be more than one movie at a time. I think there was a thought that maybe one VFX supervisor would do all of them, but that was a pretty bad thought. They ended up sort of splitting it between people…This “little” [Steven] Spielberg movie, E.T., [Laughs.] I literally had to shoot it in 35-millimeter instead of VistaVision, because we didn't have any VistaVision cameras. And the sets had to be small and pushed in the corner because Star Trek [II: The Wrath of Khan] had big giant sets all over the place. By the time I started getting worried that when Jedi came in it was going to be a clash for equipment, we actually got a production manager in to make sure that all the stuff was divvied up and, wisely, Jedi was split into three shows for three supervisors: me, Richard Edlund, and Ken Ralston. I didn't really want to do any of the space shots. I'd had enough space scenes in the other shows. So, I took sort of some of the land stuff. I did the rancor sequence. I did a few little things, walkers walking in the woods and stuff like that. It was nice for me. I could do something I hadn't done. And being in the Redwoods, we could drive there in three hours and shoot stuff.

Phil Tippett: The first thing George did was, he needed to populate Jabba’s palace. I asked to see the script and he said, well, he hadn't written it yet. And he asked, “Can you make me a bunch of space aliens, just like with the chess set? We're going to do a scene like the cantina [in Star Wars: A New Hope] only a lot bigger, so they need a lot more characters.” There weren't that many skilled sculptors around at that point in time so I pulled together whoever I could, and once a week we would meet and George would come over and look at our designs. Every Friday we may have a half dozen designs. George seemed to respond really well to three dimensional maquettes. He could see them and he could turn them around and see them in light and, you know, imagine camera angles and whatnot. And then he would pick things. He would go, “This yellow one with long legs and a snout is going to be the singer, and this little blue guy is going to play the piano. And this guy, what is that?” We go like, “That's a calamari man.” He said, “Okay, well, that's gonna be Admiral Ackbar.”

StarWars.com: Phil, before George gets there to look at your designs, did you have an overarching vision for what you wanted out of that menagerie at the outset?

Phil Tippett: No, I never do. I rarely do. My process was, I'll sit down and see what happens, you know? Sometimes I would do a sketch. I don't recall doing a sketch for any of those. And then I'd kind of make a little wire armature and then just start throwing Sculpey on it and bake it and paint it and bring it in. I learned from working with George previously that he didn't like horror stuff. He was a big fan of [Jim] Henson's. I can go either way. I can do horror or more whimsical stuff. And I always like to imbue what I do with a bit of humor or history to it, not take the thing seriously. Except when it would come up to things like rancor and then it was like, “Okay, I really need a scary monster.” For [the rest of the palace] he wanted kind of a fun bacchanal of creatures.

StarWars.com: I'd love to talk a little bit about your friendship as well as some of the things that you worked on together for Jedi, like the rancor pit sequence. Of all the people working at ILM in those early days, what do you think drew you two together as friends, as well as successful collaborators?

Dennis Muren: Well, we'd known each other by that time for probably 15 years and we worked together pretty tightly for 10 years or so at that time. I think we both really complement each other. I mean, Phil’s really an outgoing guy, hands-on, do-this modelmaker and a sculptor, a creator of creatures and objects and things, which I can’t really do at all. I’m more of a stylist photographer. I think of how something fits, how every shot has to work and you want to maximize the impact of that for the audience and also to fit within the story so it’s consistent with the film. We do completely different things and, I guess, I don’t know why we get along. We always have.

Phil Tippett: We had our own strengths, you know, and so we played to those and it was very much like a Lennon-McCartney kind of a relationship in building this thing. It was amicable. If someone had a better idea, we’d go for that.

StarWars.com: So, are you John or Paul in this scenario? [Laughs.]

Phil Tippett: Oh, it doesn't…well, I was definitely John and Dennis is definitely Paul.

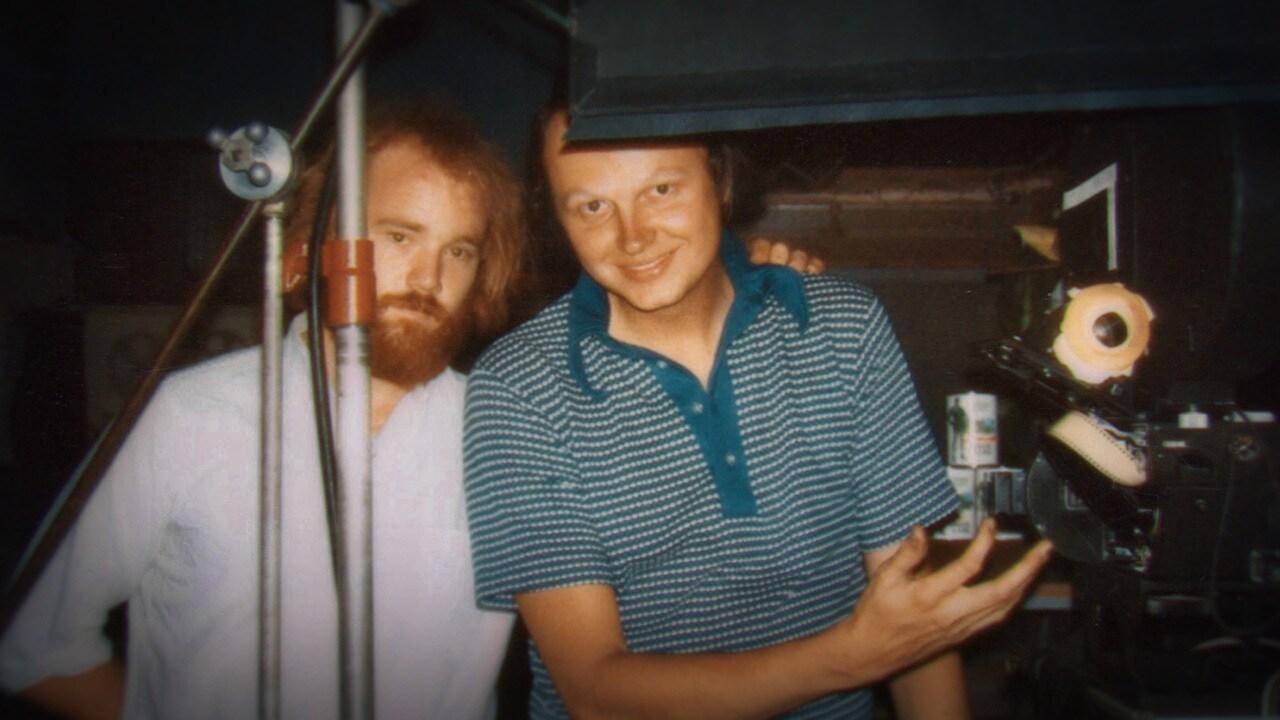

We worked together doing commercials in Hollywood at Cascade Pictures. And I think we were like-minded. We would all get together occasionally for a film night and run our own 8-millimeter and 16-millimeter movies and show each other what we were working on. All the people that submitted things were like, monster guys, you know? There was a tendency to do things like King Kong or the cyclops from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. I had just graduated from UC Irvine and I was really influenced by painting and conceptual art. [One night] I was getting in my car afterwards and Dennis was getting in his car and he came up and that really started the relationship. Dennis could see that I kind of thought outside of the box.

Dennis Muren: It's not so much a matter of trust because we mostly trust everybody we work with, but you kind of know what you're going to get when you've worked with somebody and you can get an idea of when it's going to be done, how it's going to look. You know, you have a little input if something bothers you and vice versa, Phil has input in what I'm doing. And we're all comfortable doing that.

StarWars.com: Yeah, you develop a shorthand with each other, too.

Dennis Muren: Yeah, that's right. And we have a number of friends like that. ‘Cause we all [watched] the same stuff when we were kids. And we respond to the same things in dailies. And we're fortunate because the audiences seem to like that same thing also. If they didn't like it, wherever would we be, right? We’d make an avant-garde film somewhere.

StarWars.com: We wouldn’t be having this conversation.

Dennis Muren: [Laughs.] No, no. It'd be a much smaller community.

StarWars.com: Dennis, as the VFX supervisor, you have to have a vision, but you're also trying to execute on the vision of the filmmaker. Do you remember any challenges on Jedi bridging that gap between what you saw or what you thought the scene needed to be and what George was telling you?

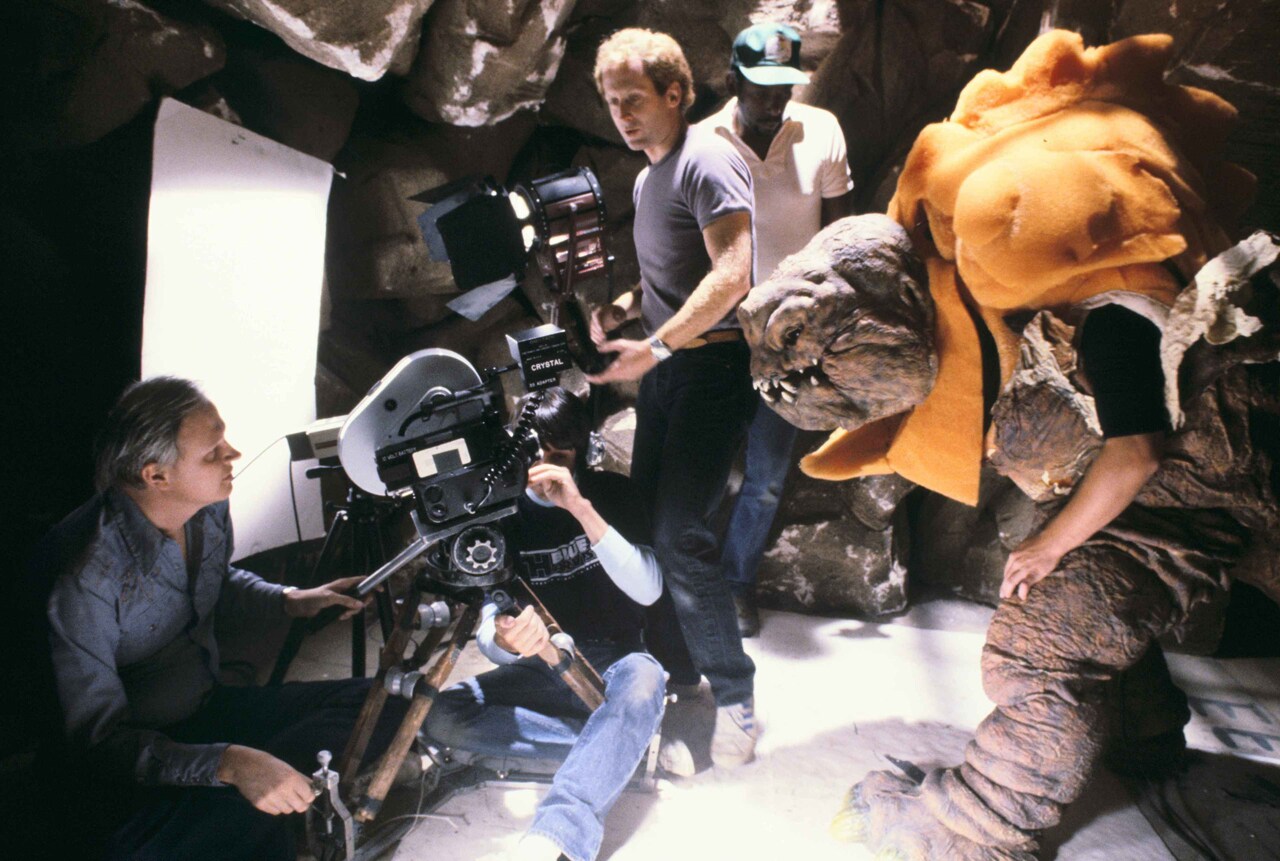

Dennis Muren: On the rancor, [at first] we were going to try a man in a suit. We built a little rough suit and I thought we could have gotten somewhere with that. It wouldn't have looked like what's on the screen now, but we could have done something. George just thought it was too clunky looking and may have just spiraled into something really fake. Would it look too much like some of the other costumes that were in the movie, you know?

Phil Tippett: When I designed rancor and George went for that he decided, “Well, we're going to make that as the best Godzilla suit.” That's what he said. But I hadn't designed rancor to be that. I designed it to be more like a stop-motion puppet. And so when we built the man-in-a-suit version of rancor, I was dubious about it. And then Norman Reynolds sent over a set for rancor’s cave and I got into the suit, and [creature technician] Kirk Thatcher got into the suit, and [sculptor] Dave Carson got in the suit. And Dennis shot shots that were storyboarded. It just looked like s***.

StarWars.com: What wasn't working for you with those shots? Was it just so clearly a man in a suit?

Phil Tippett: Yeah. It wasn't designed to be that. It's roughly got the physiology of a human. You have to make arm extensions and whatnot. But even the behavior, there's a corollary between the behavior of an anthropoid ape and a human being. When you're making alien creatures you can pretty much do whatever you want as long as it feels like what it should be.

We were shooting tests during the week of the various creatures that we were doing. One day for the blue character, Red Ball Jet [later renamed Max Rebo], it was the end of the day and we had to shoot a scene, and I had built the thing to test it to make sure the thing wouldn't rip or fall apart. And George had selected Rick James' "Super Freak" as the temp track for us to pantomime to. I got in the suit and was pantomiming to it. And my wife Jules shows up to pick me up because we only had one car at the time. And she's like, “Well, where's Phil?” He's in the suit. And she goes, “No…that couldn't be because Phil has no sense of rhythm.” You channel yourself and then you actually become the character and a guy like me who has absolutely no sense of rhythm and has never danced in his life can put this thing on and all of a sudden, you know, think you've got it. The characters kind of come alive like that.

StarWars.com: How does that transformative quality work for you when you're switching then to the rancor and it's more of a hand puppet than a full body suit that you're embodying?

Phil Tippett: Well, a monster is a monster is a monster, and it doesn't have to do that much other than to be a threatening entity. You figure out basically what the water weight of the thing is based on how tall it's supposed to be. And rancor was like 10 or 12 feet tall, and then from there you could figure out how to do the pantomime. It got to this point where we were looking at the dailies and George ended up saying, “Okay, go ahead and do whatever you want to do. We've run out of time.” And we had kind of been preemptive. Tom St. Amand built a stop-motion armature for the thing, and then Dennis realized we're up against the gun and we just had a few months and the stop-motion setup is sort of taking too long. So Dave Carson built a miniature set. We built a hand and rod puppet so that we were able to generate footage a lot more quickly.

StarWars.com: I think it was August of 1982 when George looked at the man in the suit version and shut it down. You've been working on this film for over a year and a half at that point and now you're back to square one with this particular creature. Do you remember how you felt getting that news?

Phil Tippett: We were happy.

StarWars.com: [Laughs.] Oh. That's not the answer I expected!

Phil Tippett: We weren't happy about the schedule, but we knew we’ve got to do something else because this didn't work. And we weren't confident that it ever would, [even] as we were building it up. Number one, we didn't have a whole lot of time, or the time that it would take to actually do something like that. Usually, what you would do is be very careful. You would make a mold of a human body in a certain position. You would get clay and you would build it all up and then you would take molds and run huge pieces of foam rubber and then applicate that and do more sophisticated extension arms, and that kind of a thing. And we just didn't have that money or time. So, we just fabricated it out of sheets of foam using Turkey cutters — electric knives — to sculpt the stuff. Which is how we did everything pretty much. But, you know, it was the product of its process, which, to begin with, didn't start off on the right foot.

Dennis Muren: You know, I can't remember the order before we came up with the hand puppet or whose idea that was. I just didn't want to go into a go-motion kind of thing like we had done on Dragonslayer. That's a nightmare and it takes forever.

I had been kind of pushing rod puppets. I was looking for ways to speed the whole process up because these films were so expensive. Maybe it was obvious, “Let's do it with rod puppets like Muppets.” I tried it a little bit on the bike chase scenes. Some of those speeder bike chases where you see the bikes fly along or even race by camera, they're models. You see Luke and Leia and they’re done at a slow speed shooting with Phil or [assistant camera man] Mike McAlister or somebody holding a rod in the head of the puppet. I know I was looking at a lot of ways to do things faster that still looked good, you know? And maybe out of that is where we came up with a solution to this. The trick was like getting the rods and the whole set tight enough and everything. But I like that idea of being boxed into this small space and imagining what this big creature would look like.

Phil Tippett: My tendency for monsters is to not be that literal with things and to try and have a certain level of like, “What is that?” George and I differed in our ideas about what a face should be. I think things should be hard to look at until you've seen three or four shots and then you start to put together the thing in your mind. That's more like a monster to me, you know? It's like if you see a black widow spider crawling up your arm, your first response is visceral even before you think, “That's a black widow spider.” George always kind of liked to see a face that could be expressive.

StarWars.com: Would you say you have an affinity for hand puppetry and that aspect of the work?

Phil Tippett: No. You know, it doesn't really matter that much. You just project yourself into the character that you're doing. And there are master puppeteers out there that are far superior to me. But the rancor was a particular kind of a thing and I had the experience to pull it off.

Dennis Muren: The four people that are puppeteering rancor, including me and then Kim Marks, who was trying to shoot it, are all jammed to an area probably like three feet square or four feet square to be able to do it. [Tippett operated the rancor mouth and head, Tom St. Amand had Eben Stromquist’s two grips that manipulated its elbows, arms, and fingers and Dave Sosalla controlled its feet]

StarWars.com: Is that a difficult working situation? Or do you thrive in that because you all have a shorthand with each other and you're moving in concert with everybody else around you?

Phil Tippett: Yeah, it was no surprise. You know, it was just, “Okay, that's the stage.” That's what you do your performance in.

Dennis Muren: That's a lot of people in there having to perform, but that's necessary to make it look real. You just approach it as though it's real. You don't get back with a longer lens so everybody's got more room. You don't make the cave a little bit bigger so everybody's got more room. That sequence, I think really helped because the whole set was supposed to be so small and I wanted to make sure we maintained that cave opening to being like, you know, whatever it is, 50 feet around or 75 feet round. I think it helps getting really tight on it. And I'm pretty good and Phil's pretty good at being able to look at stuff and say, “Man, it looks like a hand puppet. Let's just try another take.”

Phil Tippett: We'd shoot at high speed, all over the place between 76 frames a second to 120 frames a second. The pantomime process is the antithesis of stop-motion, which is like sculpting in slow time. At high speed, if you're going to do a four-second shot, you know, you have to perform like really quickly. And we would do tons of takes because we just didn't know what we got and we didn't have any playback at that time. We would review it for dailies. George caught on pretty quickly. We'd show up for dailies and he'd go “How many dailies do you have?” Because usually we only generate one or maybe two shots a day if we were lucky. [With the rancor] we’d have like 60 takes then pick out six and send them over to Duwayne Dunham, in editorial.

Dennis Muren: It got really elaborate and we did some scenes even backwards! We only had to get this three second shot and we knew where [Phil and the rancor] needed to start, the attitude the rancor had to have, and where he needed to end up. We just had to get three seconds of that. Then you could think, you know, let's try it backwards. Let's try it shooting slow motion and have Phil move real fast and see if that gets away from the hand puppet.

Dennis Muren: Yeah. You hardly ever see the whole figure. And the top is lit really bright and the rest is really dark. We got nice eye lights on rancor. You see his eyeballs really well. So you're looking at the menace in the face; no matter how wonderful that face is, if you can see a glint in the eyes, it becomes alive. And we panned the camera all around, which you couldn't do with a lot of other techniques. I didn't want to do any of that. Just right in front of the camera. Real.

StarWars.com: That glint in the eye, I think, really helps sell it.

Dennis Muren: The drool, too. I'm sure that's Phil's idea.

StarWars.com: I’m sure [Laughs.] But I think it was your idea to shoot it like it's a nature documentary, which is a real stroke of genius. Do you remember what inspired that decision?

Dennis Muren: Reality, you know, seeing a lot of movies. It comes down to: what do you want to feel? I don't remember how many shots we had in this. Maybe about 20 or something like that. So that's a lot of times to look at it in this small space. To keep it interesting, you want to get in there and do it like Raging Bull, you know, something like that. You're in there feeling it and you can't quite see it. I wish I'd made it even darker, but at that time it was pretty risky to go dark like that.

I'm just talking about the whole thing feeling like, “Just let me outta here. I'm trapped in here!” But it's not a Raging Bull movie. It's a Star Wars movie, so you don't need to be that dramatic with the feel of it, but you do want it to feel, I thought, not quite handheld, but a little more radical and not something that had been done very much before in effects films.

StarWars.com: There's a great picture that Phil posed of the rancor having a fake fight with the Dragonslayer dragon. What was the story is behind that?

Phil Tippett: We thought it would be funny. We had both of the characters. So why not? They’re just sitting there. Terry Chostner [in the stills department] did a portrait of it.

Dennis Muren: [Laughs.] I don't remember if I was there when they shot that or not. It’s nice seeing that action. Who's going to win? I think it looks like rancor is going to win. Maybe that was the sequel that never happened.

StarWars.com: There's also a great photo of you both holding hands with the rancor, smiling and like, shaking hands with the puppet.

Phil Tippett: It’s not a story so much as I think it was the thing was finished. We were all ready to shoot. It was ready to be put before a camera. We did a lot of jokey photographs all the time.

Dennis Muren: I think it had just about come out of the mold. Here it is! But it may have been an early casting of it. You know, I just love that stuff. The smells of it, the people that are doing it, tools and technology, fluids and powders, and motors whipping these things up and then pouring it into [the mold]. I just love that. I grew up loving that and working on that at Cascade, except instead of a dragon or rancor, it was the Pillsbury Doughboy. Something was happening. Life is struggling to make life. You can see it and feel it and taste it and you can go up and touch it and change it with your hands.

StarWars.com: Speaking of hands, we’ve heard the story that one day while shooting the rancor sequence, Phil’s hand got hurt and, Phil, you got stuck inside the puppet for hours.

Phil Tippett: There was a big 5K light up on its stand and the knob had not been turned down enough. And I happened to have my hand on the thing where the light goes up and down and it just came down and smashed my hand between my thumb and my index finger, which caused it to swell up in a big blood blister. So once I got my hand inside the [puppet], it was like this yolk that had to squeeze through and my hand had swollen up so much I couldn't pull it out.

StarWars.com: In that moment, why not just say, “We have to stop for today. I'm not doing this. I'm injured.”

Phil Tippett: I didn't know I couldn't pull my hand out until I couldn't. I have very high tolerance for pain.

Dennis Muren: I don't even remember that. If it was bad enough, we wouldn't have continued or somebody else would've done it. Phil was probably saying, “Oh, I'll be okay.” It'd be really funny if I'd never known about it because he didn't want to give me the option of saying, “We should shut this down.”

StarWars.com: Beyond the rancor pit, you worked together on a few key moments, like Han being thawed from carbonite and a few parts of the battle on Endor. For Han, what was the challenge with this particular sequence?

Dennis Muren: You know, I don't remember much of the history of it, but the solution was kind of simple and it was just to invert it and have a light inside of this thing, shoot the smoke, and then break away, stop-motion wise, the casting that was on the outside.

Phil Tippett: We had the carbonite rectangle, and I just pulled the mold off of that and made a wax shell from that, and drilled and then painted it up and made this fish tank for it. Then I poured wax in it, and the wax was like a quarter of an inch deep. I would pump in a lot of smoke and then I would go in from the back with an X-Acto blade and just start animating these holes opening up.

Dennis Muren: There would always be these sort of jumpy shards of light coming out. Who knows what's going on, but you know something's going on the inside there. And hopefully it's going to be satisfying and work. And it did, thank God.

Phil Tippett: You get all that stuff in one take for that element, and then I made a foam rubber casting of Harrison Ford's face and painted that up to look like a human, and put that on a green screen that Bruce Nicholson comped in later. We had that as a hand puppet, so when all the carbonite goes away, then he can open up his mouth.

StarWars.com: Knowing what you know now, having worked in the industry for so many years, would you have approached either sequence any differently with the tools or the knowledge that you have now?

Phil Tippett: No, you know, we didn't have any time, so it was just running and gunning it. The schedule drove everything.

Dennis Muren: You know, I never thought about that. I like that look much better than if it had been a big CG show, which is the way it would've been done now. So much of [digital graphics] looks really fake. So much of it doesn't have any relationship to the real world because there's no physics involved in it. [For Han,] I think what's in the film is something that is organic and that the shards of light are coming out with something shimmering is real. You kind of see that occasionally in like a snowstorm or something with a light. It's a lot you can relate to.

Phil Tippett: And then later, I think it was for a Christmas party, we put together reels of silly stuff. So, I did a pantomime of the Han Solo puppet lip-syncing to Maurice Chevalier's "Thank Heaven for Little Girls." Stole the show.

StarWars.com: Why do you think this film in particular, of the Star Wars films, has such an enduring resonance with people that it is something that we're still talking about 40 years later?

Phil Tippett: Well, for one thing, both Lucas and [Steven] Spielberg were very well aware of film history. And what you can do with special effects is that you can generate a great deal of spectacle and things that you had not seen before. And in a science-fiction fantasy setting, it was new. Nobody had seen anything like that. George had this thing about race cars. He wanted to see spaceships flying like race cars. George always wanted, if you're doing a shot that had speed, it was to see things coming at you. It was a new coat of paint on an old genre with new technology.

StarWars.com: What is Jedi's place in the history of all special effects and cinema, in your mind?

Dennis Muren: I'm glad that Jedi was a big hit…It was quite a wrap up and it always did seem like it was the end of the series. And what an amazing thing, for me and I'm sure for everybody else to work on, to go into this little space film that we thought, “Who knows what's going to happen to it?” And then eight years later, wrapping it up and each one is satisfying to millions of people. It was amazing. Period.