In conversation with Tom Spina, McVey, who designed the original Star Wars: Return of the Jedi icon, discusses making the 1:1 statue.

Tony McVey, the sculptor who designed and fabricated Salacious B. Crumb -- including a new 1:1 replica statue from Regal Robot -- and many other denizens of the galaxy far, far away, intended to have a career as a graphic designer.

Growing up in Glasgow, Scotland, McVey fell in love with movie magic and special effects after his father took him to see The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, with stop-motion by Ray Harryhausen. “I'd never seen anything quite like that before, so it really captured my imagination,” McVey tells StarWars.com. After the family moved to England, a then pre-teen McVey became immersed in researching Harryhausen’s other works and the world of stop motion animation. He can still remember the day he learned about King Kong. “(My dad and I) were standing at a bus stop waiting for the bus, it was taking forever to come. And he started telling me, for some reason, about this movie about a giant ape climbing to the top of the Empire State Building and swatting at bi-planes and being shot off. And I thought, ‘Wow, I have to see that.’ And I did see it eventually in a movie theater when I was 13, was on a double bill with The Thing from Another World.”

But when it came time to graduate and enter the world of higher education, McVey says he was encouraged to spend his time on something with a little more job stability. “I went to art school (in Southampton) for three years and studied graphic design, which was totally boring for me,” McVey recalls. “I was advised to get into that because that's where the money was. If you wanted to be an artist, be a graphic designer, get into graphics.”

Ironically, after McVey finished the program, he couldn’t find any work in his field. So he took his skills and applied for a job as a model maker in the taxidermy unit of the Natural History Museum in London, where he worked for four years creating sculptures for display. That job connected McVey to Arthur Hayward, who had worked with Harryhausen for over a decade, sculpting creatures and effects “from Mysterious Island up until The Valley of Gwangi.” During their downtime on the job, McVey would comb through Hayward’s scrapbooks and examine an Allosaurus model that had been used for Hayward’s final film. Their shared love of movie making eventually led McVey to working in film. Looking back on it, McVey says his parents probably thought his foray into production was little more than “a phase I was going to grow out of and I'd come to my senses and get a real job,” he says. “But I'm still waiting for that to happen.” After a stint with Jim Henson’s studio working on The Dark Crystal, Phil Tippett brought McVey on for Star Wars: Return of the Jedi. McVey sculpted the bodies for the Gamorrean guards, helped Tippett with the first incarnation of the rancor suit that was intended to be worn by a human, and worked on the armature for the massive rancor hand that gripped Luke Skywalker actor Mark Hamill in close-up shots. Occasionally, he even stepped into the hand, he says, a favorite place to pose for photos among the crew.

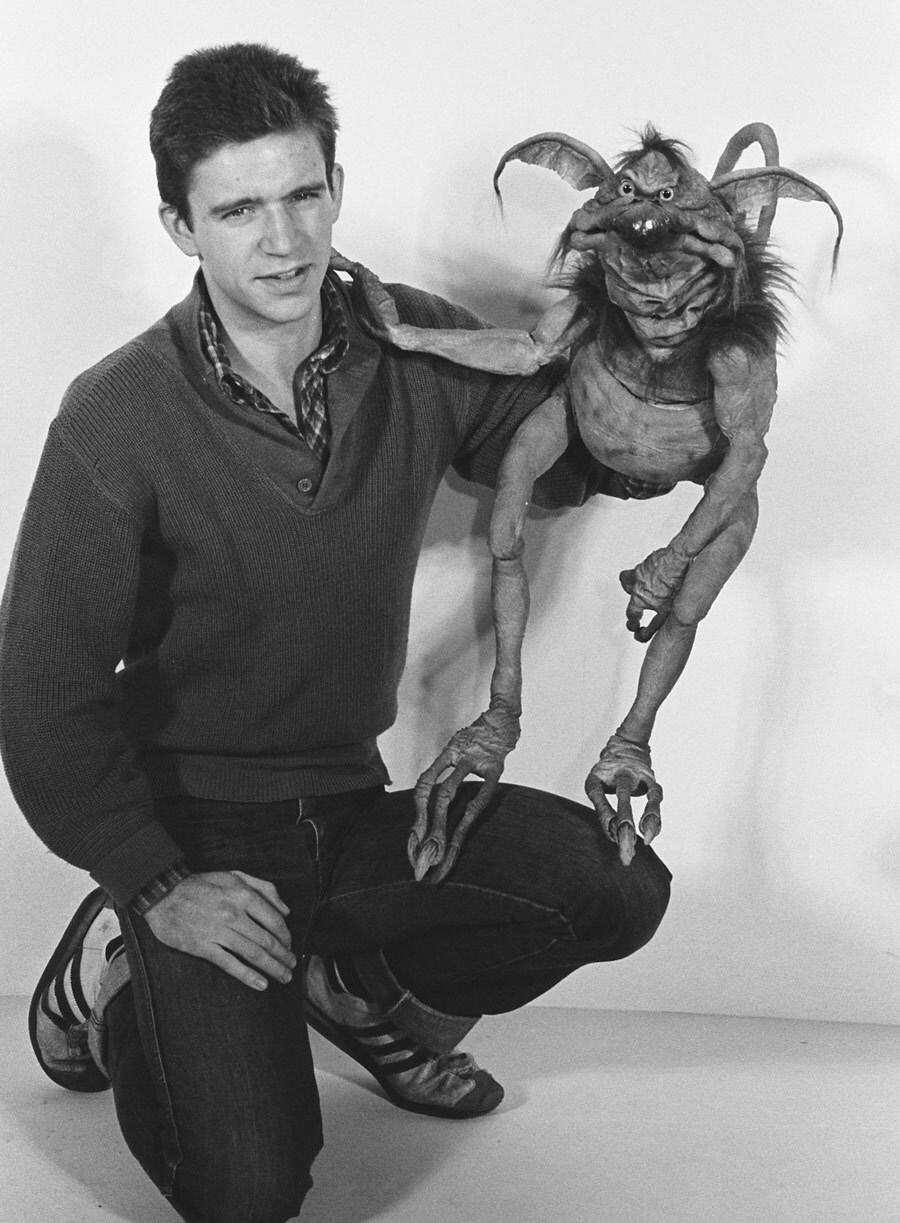

But while McVey helped with the look of Sy Snootles and many background aliens for Jabba’s Palace, his work is synonymous with the cackling court jester that perched on Jabba the Hutt’s tail: Salacious B. Crumb. The Kowakian monkey-lizard was cooked up in a single night -- in about 10 minutes, McVey recalled in The Art of The Mandalorian Season 1 -- and was intended to perch on the shoulder of Ephant Mon, a blink-and-you-miss-it part of the crowd. However, the crew, including George Lucas himself, became so enamored with the creature that the puppet quickly got promoted to Jabba’s minion, coming to life at the hands of puppeteer Tim Rose and Mark Dodson who provided the voice. “One day I came in and here was Salacious and I fell in love with Salacious,” Lucas said in The Making of Return of the Jedi.

Recently, StarWars.com sat down with McVey and Regal Robot’s Tom Spina to talk about sculpting the new, limited-edition Salacious replica.

Tom Spina: Tony had worked with us previously on the Gamorrean Fighter maquette from The Mandalorian. It's the first thing we got to see from Season 2. I immediately fell in love with the sculpt. I thought it was brilliant. Then one of our other sculptors here saw it and he said, “Look at those hands. That's McVey.” [Laughs] “Nobody does hands like Tony McVey.” So sure enough, we find out that it was one of Tony's sculpts. That was something that that really kind of put us together. We got to talking. We both love a lot of the same old stop-motion and things like that. And so, you know, the Salacious thing came out of [of that].

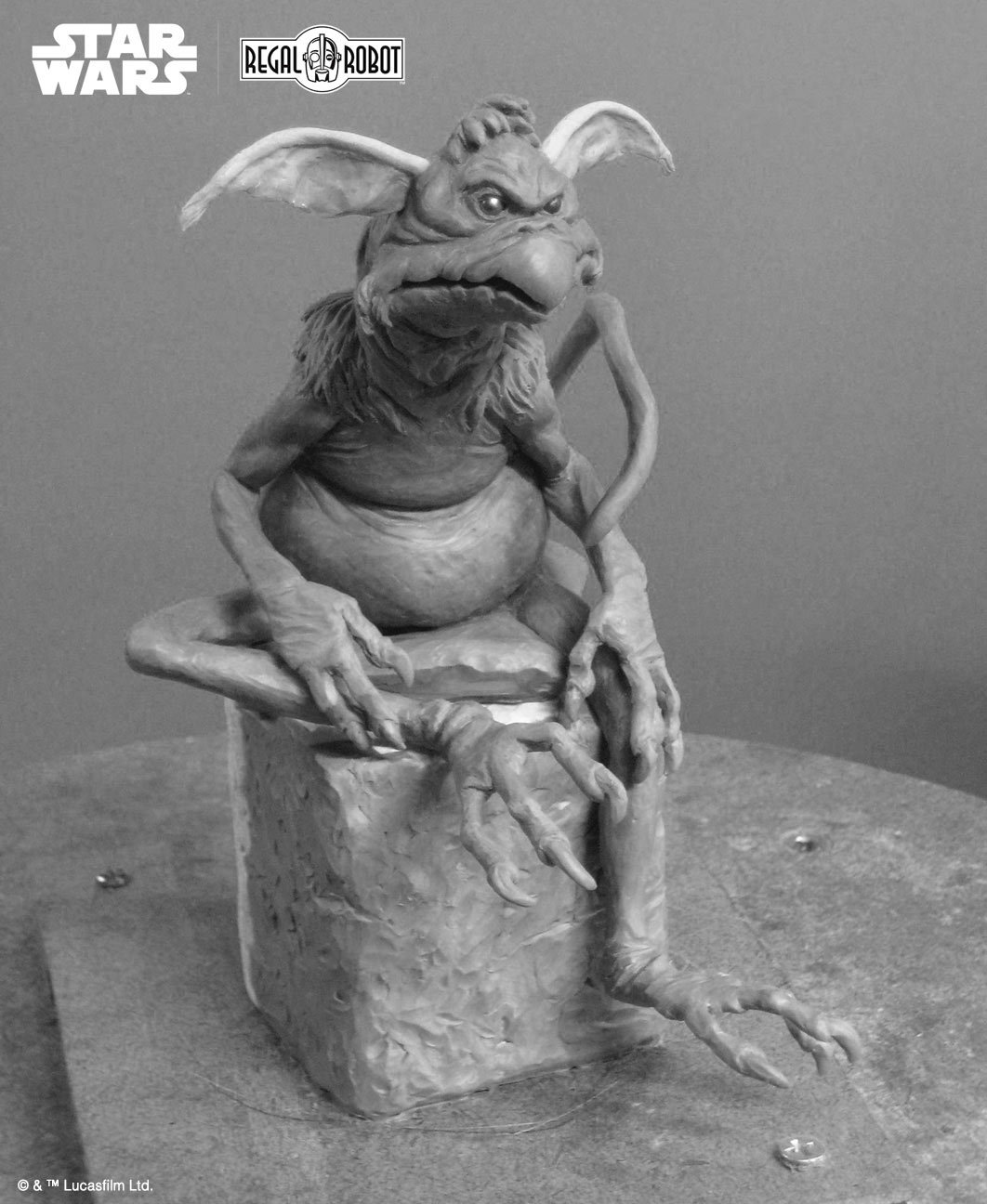

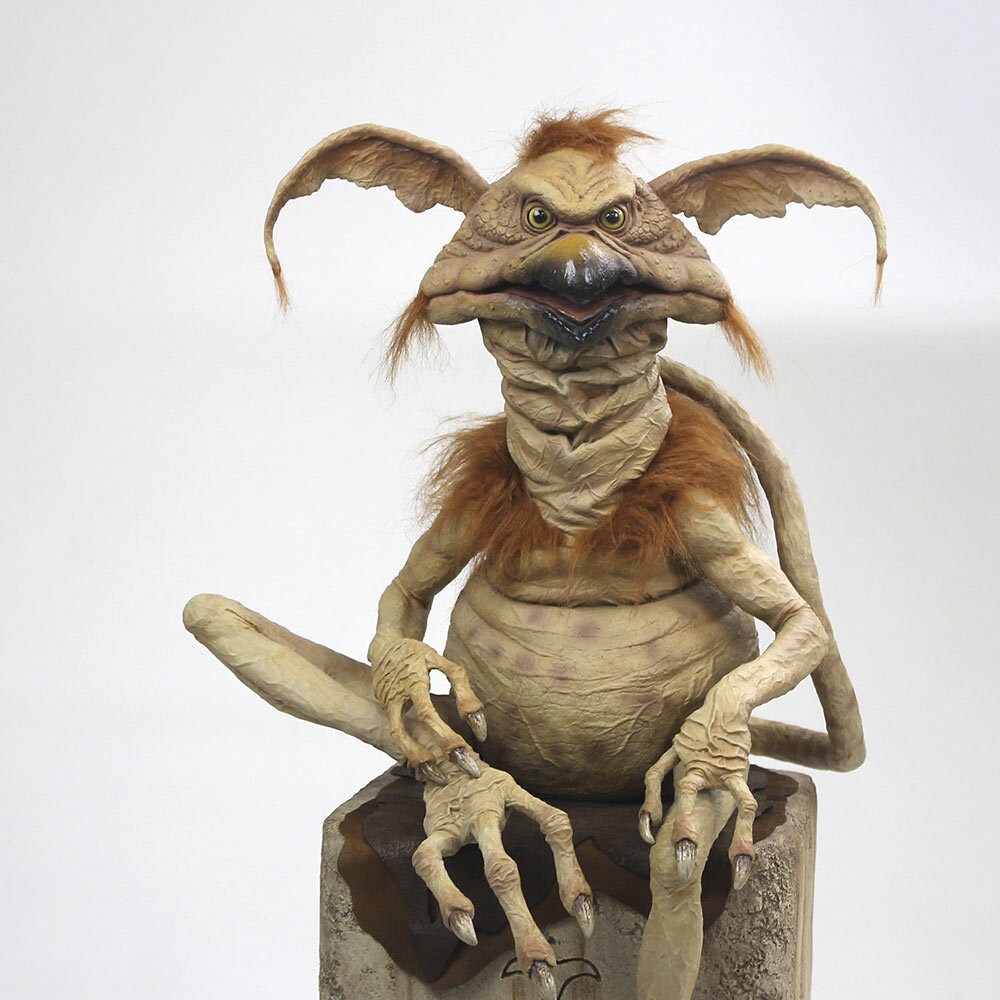

Through the whole process, I bugged him with photos and really, really pushed to match not just the character, but the prop. And Tony does -- and I don't know, he’s probably too humble to say -- again, brilliant hands. But the texturing on the skin that he did looks like latex and cotton fabrication or latex and tissue, like you would do when you're fabricating a prop like this. Everything on it is made to feel like that real prop, to look like the prop, to have that sense of kludged together effects [from a] guy working in the middle of the night, I'm sure, after many, many days. That was the whole goal. And much like Tony's brilliant sculpt on the original prop gave [Salacious] a great foundation, Tony's brilliant work on our sculpt gave me and our team inspiration. When we then went to do the paint mastering and to do the finished work on it, it has all these great little nooks and crannies that are just made to catch a wash and to pop those details and everything.

StarWars.com: The legend I have heard, Tony, is that you came up with the original in a night. He was going to be this little creature sitting on the shoulder of a background alien. And then everyone just fell head over heels for him and he became Jabba’s little guy. And then, of course, Tim Rose made him this unforgettable screeching thing. So I'd love to hear some of your recollections, both from working on the original, but then also taking that expertise and bringing it into this sculpt.

Tony McVey: OK, well, let's see if I can remember that far back. Phil Tippett came to me one day in the middle of the 11 months I was working on this project, and he said, “We need a little pet character for one of the background of aliens.” It was for Ephant Mon, which I also worked on. “We need a little pet for this guy. Can you come up with something?” So I went home that night and I scribbled something on a piece of paper. It's a cross between a parrot and a monkey. And I brought it back the next day and I showed it to him. He said, “OK, go ahead and make that.” It was as simple as that. There's nothing to it. Just a little background monkey character. And I fabricated the body, which was then stuck to some kind of a, I think, it was a resin-impregnated canvas.… I fabricated the arms and legs, a dowel with rope joints and cover that up the foam to make muscles, and the head was sculpted and cast with foam latex right there in the creature shop. And once I got that back and fabricated a neck for it, we put the skin on it -- it's just tinfoil, wrinkled up tinfoil. I made the mold off of that and cast it in latex. It was very simple. It was very basic. If I'd known it was going to be put on Jabba's tail, I would have spent more time on it because it was never, ever intended to be up front and center like it ended up.

Tom Spina: There's something about puppets in general. I got my start in puppetry and I find there are people you'll talk to who would swear to you that, you know, that they've seen a puppet character blink even when it doesn't have the capacity to. And it's because there is an immediate connection between performer and character that just has this direct one-to-one movement. And it imbues these things with a level of life that I really think fools you into thinking that they are more articulate than they really are.

The original prop is still in the [Lucasfilm] archives. We do a lot of research at the Skywalker Ranch archives and over the years with my other company, we've done restoration work for them on a number of pieces. So we did get to go and look at that real puppet. We got to spend many, many, many hours and days, actually, with it. We were able to measure things. We were able to take photos and really provide Tony with a foundation to make sure that this new sculpt was going to be one-to-one, 100% the same size, the same look, etc. And, you know, we sent Tony a lot of reference photos. Probably way too many reference photos. He can probably sculpt in his sleep at this point. [Laughs]

StarWars.com: So once you twisted Tony's arm, you got all of that research in the measurements and all that, how long does it take to create the replica start to finish? And also, Tony, I am curious if now that he's in the spotlight and this is something that's going to be in people's homes, if you are tempted or added additional details that you would have liked to see on the original.

Tony McVey: Not really, because I knew Tom was going to look at this thing with the eagle eye and say, “Oh, you can't do that. That wasn't in the original, dude, you can't put that in there.” So, no, I just tried to stick to what was in the original piece. That seems about the safest route.

Tom Spina: We did talk that through early on and it was because as an artist, too, I know that tendency of if I'm redoing something I did in the past, man, I want to make it better.

Tony McVey: I had free time to work on it so I could just devote my time to that. But it still took a long time. About six months.

Tom Spina: Well, he's bigger than people think, too. It's the sort of thing that it's careful, cautious, slow work when you're trying to replicate something. It's fast work when you're creating something for the first time! But to replicate it? It's a slog. You know, and I feel slightly bad for having asked Tony to do that.

Tony McVey: But only slightly.

[Laughs]

Yeah. I've gotten used to all that stuff because I've been doing this for 48 years now. So you kind of get into a pattern of doing things. So I guess I'm there by now. This is the fourth one I've done.