As Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back and the memorable Battle of Hoth turn 40, StarWars.com speaks with George Lucas, Ben Burtt, Joe Johnston, Dennis Muren, and Phil Tippett about the making of the famous clash in the snow.

On May 21, 1980, Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back made its theatrical debut. To celebrate the classic film’s landmark 40th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Empire at 40,” a special series of interviews, editorial features, and listicles.

In May 1977, Star Wars took the world by storm, going on to become the highest-grossing film of all time and garnering several Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Picture. So a sequel was something of a no-brainer, to say the least. And that sequel would be The Empire Strikes Back, which opened on May 21, 1980. Darker and more emotional than Star Wars, Empire also presented another leap in visual spectacle, with more locales and action sequences, and a much bigger scope than its predecessor. Today, 40 years later, fans often cite it as their favorite Star Wars film, and many consider Empire among the finest motion pictures ever made.

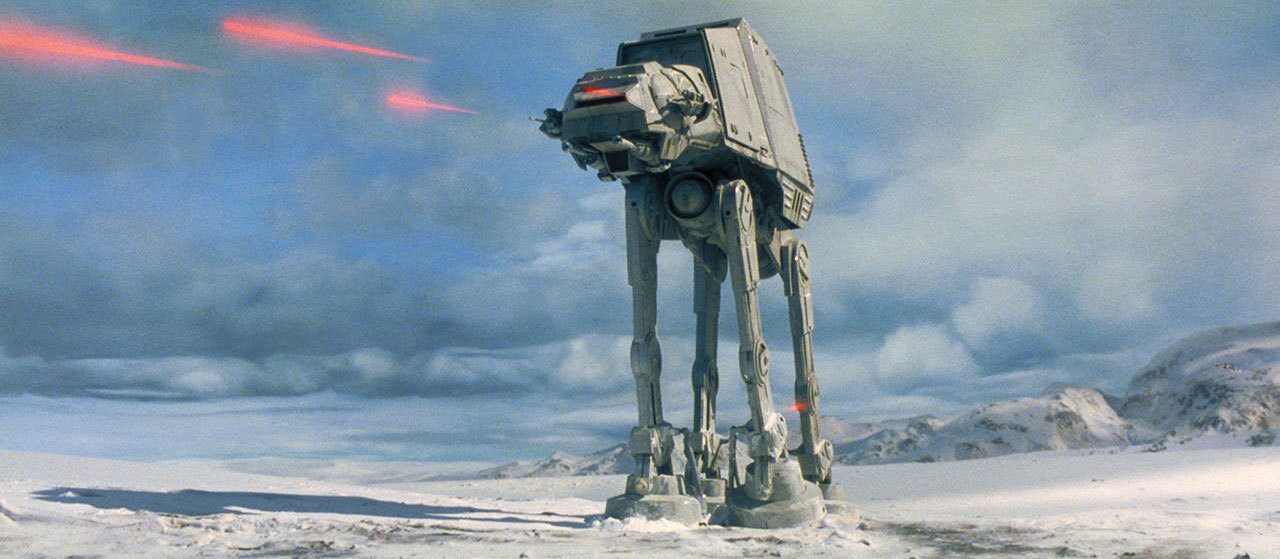

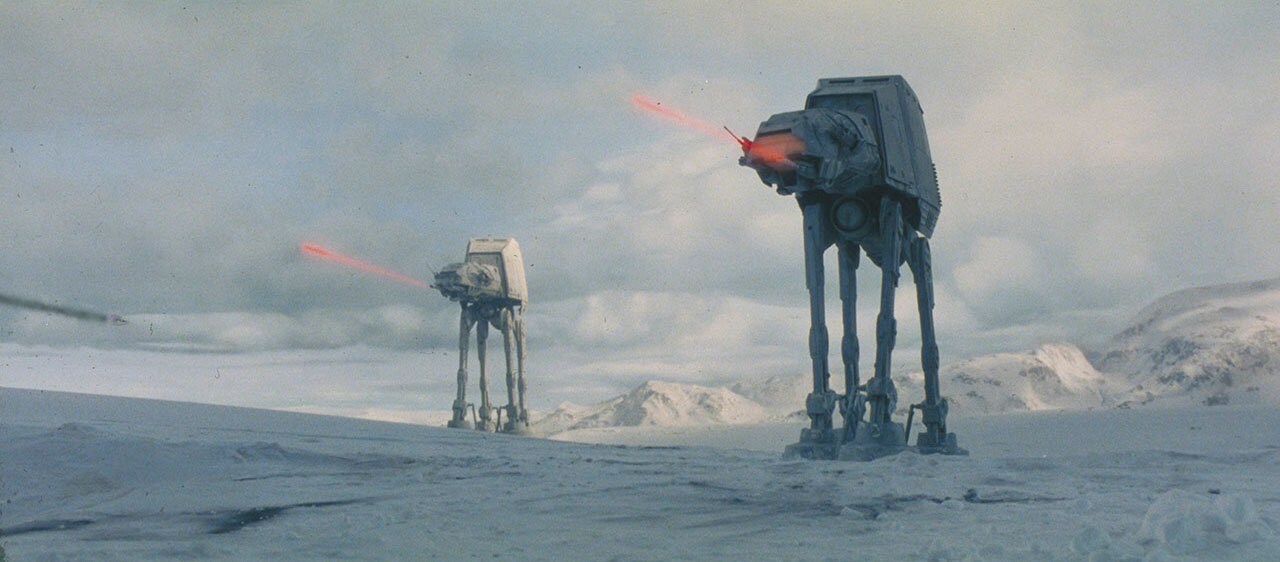

Among Empire’s many memorable moments and set pieces is undoubtedly the Battle of Hoth, in which the rebels square off against Imperial forces on a planet of snow and ice. The Empire attacks in towering AT-AT walkers, while the rebels, led by Luke Skywalker, fly small snowspeeders in an effort to thwart the offensive. There had been nothing like it in Star Wars, and it stands as one of the great sequences in the entire saga.

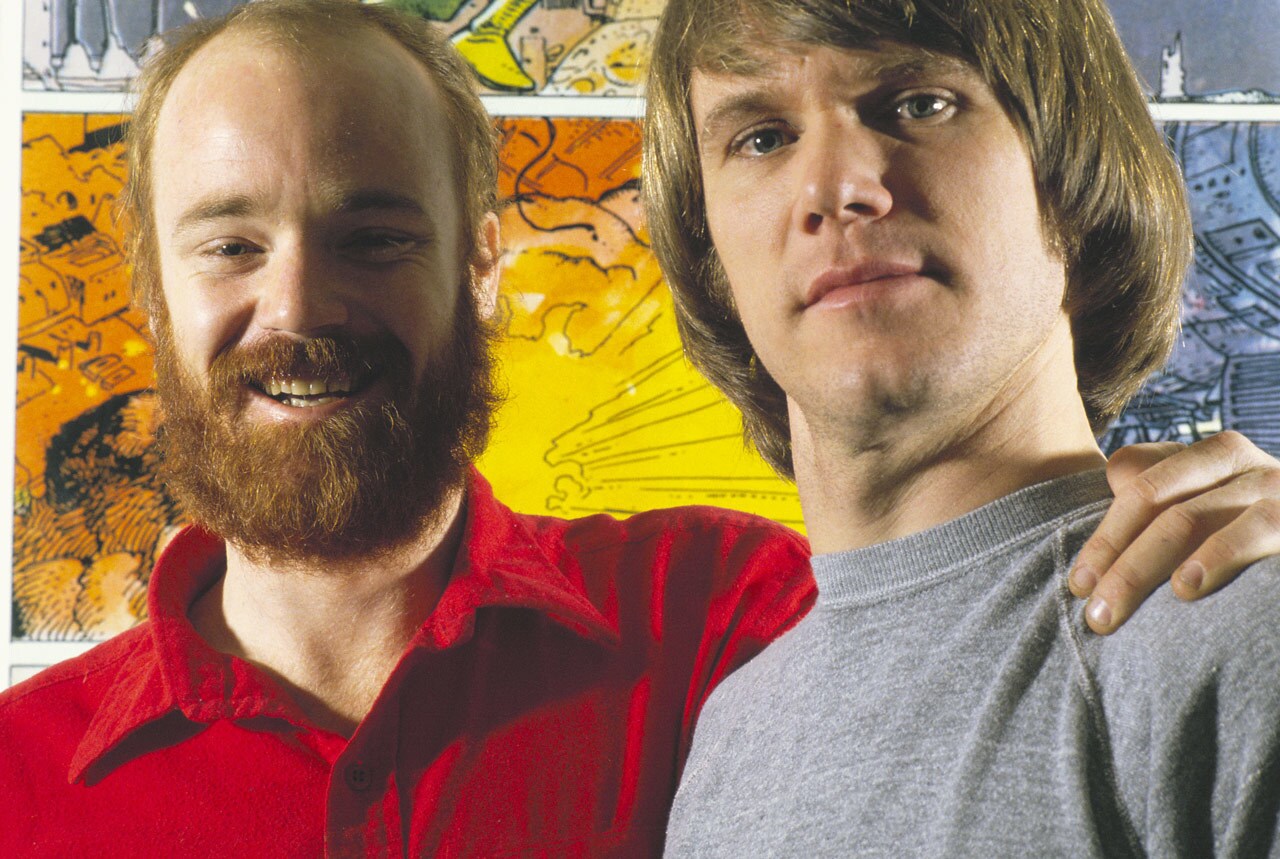

To mark the 40th anniversary of Empire and the Battle of Hoth, StarWars.com spoke with some of the greatest talents behind the film and the sequence -- legends George Lucas, Ben Burtt, Joe Johnston, Dennis Muren, and Phil Tippett.

Where the Fun Begins

On September 21, 1977, following the surprise and massive success of Star Wars, Twentieth Century Fox and The Chapter II Company (a subsidiary of The Star Wars Corporation, formed for the sequel to Star Wars) signed an agreement for the production and distribution of what would become The Empire Strikes Back. George Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz would bring back many of those who created the look, groundbreaking effects, and sounds of Star Wars for the follow-up.

Joe Johnston, visual effects art director: I wasn’t aware that I had a career when Star Wars came out. It started out as a six-week job to do some storyboards and the more I worked there, the more things I was asked to do. At the end of the show [Note: “show” means “movie.”], they were calling me the visual effects art director, I think was my title. We all knew there was going to be a sequel, but I had just come from what I thought was the beginning of a career in industrial design and at that point I thought, “I don’t know where this is going, but I can always get my industrial design job back.” [Laughs]

I was working for a guy, [product designer] Chuck Pelly, out in Malibu. He had a design studio out there. It was a good job. It paid exactly the same as the Star Wars job paid. For a while there I was thinking, “I’m going to go back to Chuck Pelly, and say I need a raise.”

Then Battlestar Galactica basically came in. [Creator] Glen Larson came in right at the end of Star Wars and said, “I want to hire all you guys, I want to basically hire ILM [Industrial Light & Magic] to design and do the visual effects on Battlestar Galactica.” So that was another six-month job.

Sometime during that time, toward the end of that six months, I think we finished in December, Gary Kurtz said, “Hey, we are going to do a sequel to Star Wars” -- I’m not sure if they had a title for it yet -- “and we’re building a new facility in northern California in Marin County. Do you want to come up and continue, basically, what you were doing for us?”

At that point, I knew that I had a job. At the time I don’t think I referred to it as a career because I still didn’t know where it was going.

Dennis Muren, visual effects director of photography: After Star Wars, I went onto Close Encounters [of the Third Kind] and Battlestar Galactica. I kept expecting to hear from George [Lucas] that there would be a sequel. He never said for sure but he had talked about it. And then finally, like after maybe a year or so, it happened and I heard from him, and moved up to San Francisco and we set up here in the Bay Area, and we started from scratch.

It was a talented group of people that were down on that first show, and about 10 of us or so moved up north, and then hired a lot of local people and other folks around, got some others from L.A. We were just so self-contained, and I think being isolated from L.A. meant that we just totally focused on the work.

Joe Johnston: I moved up to Marin County in April of 1978. The ILM building existed but there was nobody in it; it was completely empty. George said, “You can have an office over here in” -- it was on Kerner Boulevard – “the new ILM building,” or you can have an office in this house that he had bought behind his Park Way house. We called it the Ancho Vista House on Ancho Vista Street. I said, “I’d much rather be here if I’m going to set up an art department. There’s nothing to do over there because there are no employees yet.” I said, “Let me add a drawing table in this house and I’ll be 100 yards from where you’re working, and if you want to come down and talk about stuff, we can.” But I don’t remember when I first read the script. I know that George was working on it at the time.

Ben Burtt, sound designer: I started working on the film about nine months or so prior to its release. We were able to start spending full-time collecting sounds, going through the script that George had, looking at the artwork that was being developed.

Phil Tippett, stop motion animator: Well, as soon as Star Wars was released, I got contacted by producer John Davison, who I later went on to do Robocop and Starship Troopers with, and he had seen my name and [stop motion animator] Jon Berg’s name in the credits in Star Wars from doing the cantina scene and the chess [“dejarik,” in-universe] set. So he just contacted me and came over to my house with Joe Dante, and they were making Piranha. So they hired us and we worked on that. Then a number of other projects came through that I don’t really recall, mostly probably television commercials in Los Angeles at the time.

And then I got on board on the Empire Strikes Back team, and George relocated probably about 12 or 15 of us from L.A. to work on Star Wars. I was not an employee of ILM, I was an independent contractor. So, we all relocated to the Bay Area and started working on Empire.

Dennis Muren: That was great and it was terrifying. It was the hardest movie I ever worked on because we did have to relocate, all we had was a big empty warehouse. We had this massive movie, and George had a lot of the artwork done, and when I first saw what was going on -- he’d done stuff with Ralph [McQuarrie, concept artist], and some with Joe Johnston, and it was just huge. It was way beyond what Star Wars was.

George Lucas, Star Wars creator and The Empire Strikes Back producer: You have to be a cheerleader and you just have to convince them that this will work, it’ll be great. On the first one, the production crew on the set, except for the art department, just thought it was a joke. And they were not that interested in the movie or helping or doing anything except getting their paycheck. ILMers were always enthusiastic because they were very young. And young people are enthusiastic. [Laughs] They knew we were doing something that had never been done before and so that excited them and that kept their morale up. And even though we went through some very hard setbacks, I had to go up and be a parent and say, “We can do this. We’re not going to give up. We have to keep going.”

Ben Burtt: The first film, we were all innocent, and made a film, basically, that we wanted to see ourselves. And even though there was lots of stress to get it done, we were young and we were vigorous and what did we have to lose? There was no reputation to uphold, and no one foresaw that there was going to be a reputation. We were making a science-fiction movie that we thought the audience who enjoys The Planet of the Apes or Logan’s Run would like, or a Ray Harryhausen movie -- a smaller audience, not a worldwide general audience. But now we were all defined as award-winning geniuses, and that put tremendous pressure, and I have to say, Empire, in terms of the stress level on me -- going back to my career -- was just about as bad as it ever got. Because the expectations I had on myself, more than anything else, drove my daily stress levels. I felt like, “Oh my gosh, we did so well. We hit a home run, didn’t expect it, and now I’ve got to hit another home run or maybe two, and win the World Series!” It was kind of a reckoning as to how we are going to survive it, because it was so much high expectation to do it again. ‘Cause the lesson you learn is you can't really do the first Star Wars movie again.

Dennis Muren: And as far as the technical side, it was much harder, also. They visited many lands; you didn’t just fly through space most of the time. There was this big scene, you know, that took place on an ice field in broad daylight, which meant there would be matte lines, which we always had trouble with. It would be a major problem for that whole major scene of the movie.

That “major scene” is the Battle of Hoth -- the action set piece of The Empire Strikes Back, which would find the rebels clashing with Imperial forces on a world of snow. It fell chiefly to Joe Johnston to develop the look of the sequence.

Joe Johnston: The first thing I did on Empire, and specifically the Battle of Hoth -- there was no written [Battle of Hoth] sequence in the first script that I read, and this was typical of the way George would do the action sequences. There would just be a blank, and he would say something -- the example I remember is from [Return of the] Jedi, where the script said, “Luke and Leia jump on a speeder bike and race off into the woods.” And then there’d be a blank slot. [Laughs] I think it was something like, “The Imperial trooper crashes into a tree and they run off into the forest.” He would basically leave all the action out knowing that we were going to be using storyboards and models and whatever technique we could. We would figure out what the action sequence was.

We had a lot of freedom. George had ideas about how to do things but he really wanted us to explore the best ways to figure out the action. Specifically, to the Battle of Hoth, I just remember him saying, “Just come up with shots. They don’t even have to be connected. Just come up with cool shots that would show some ideas about how this how ragtag band of rebels on this snow planet defend their base from an overwhelming force of Imperial soldiers.” At that point we hadn’t designed the walkers yet. We knew they were going to have some kind of mechanized equipment, but it wasn’t specifically a walker.

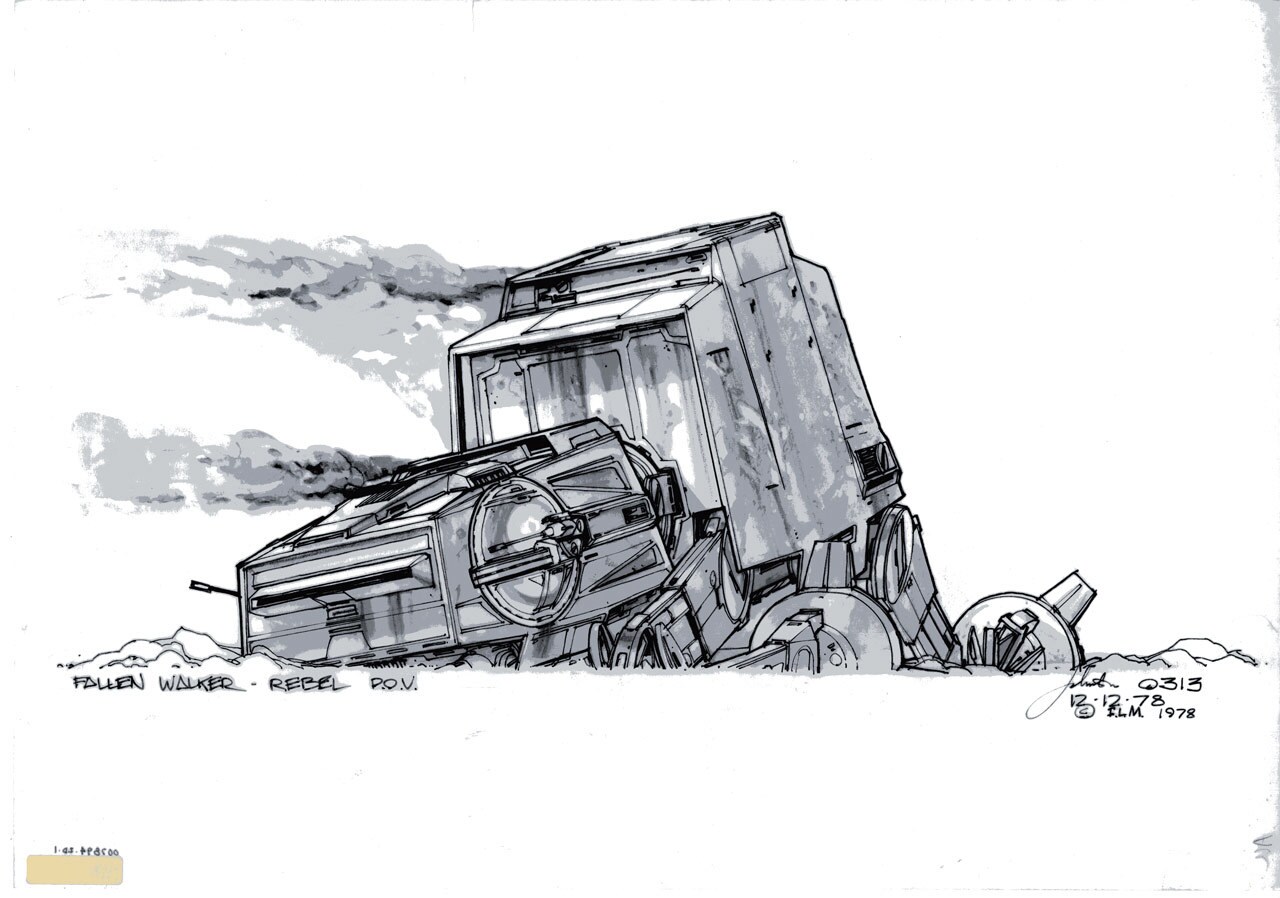

The interesting thing about the Battle of Hoth is that the rebels lose. They lose completely. They lose everything. They all go flying off into space at the end of it.

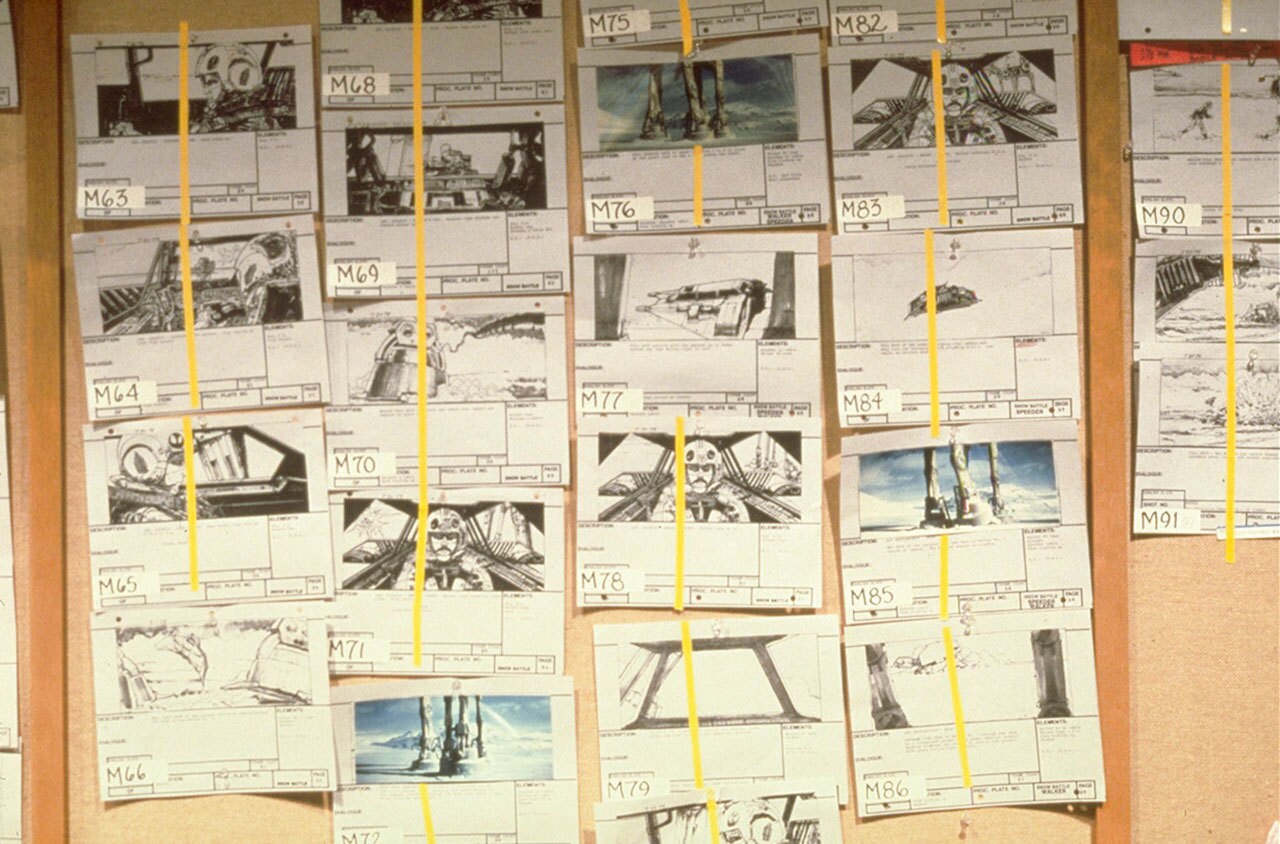

I must have spent a month or longer just drawing shots. I sort of did them in storyboard form, because I was thinking I’ll be able to connect some of these eventually and make sequences out of them, but I would draw a stack of interesting angles and shots and things. George would come in and he’d go through them and say, “Yeah, that’s cool, let’s save that one.” Other ones he said, “I don’t know how to use that.”

But eventually we came up with a set of drawings, with his input, saying, “Use these three shots,” and -- at the time I think they were tanks, we were drawing them as Imperial tanks -- he said, “Have the Empire forces come over this hill.” So we went back and forth and had sort of a rough sequence by the end of it. Of course, it continued to evolve until -- [Laughs] I’m not sure that any of those original shots even made it into the final sequence. It was sort of a way to jump off and get started onto the way to tell that story.

"We Just Called It the Snow Walker"

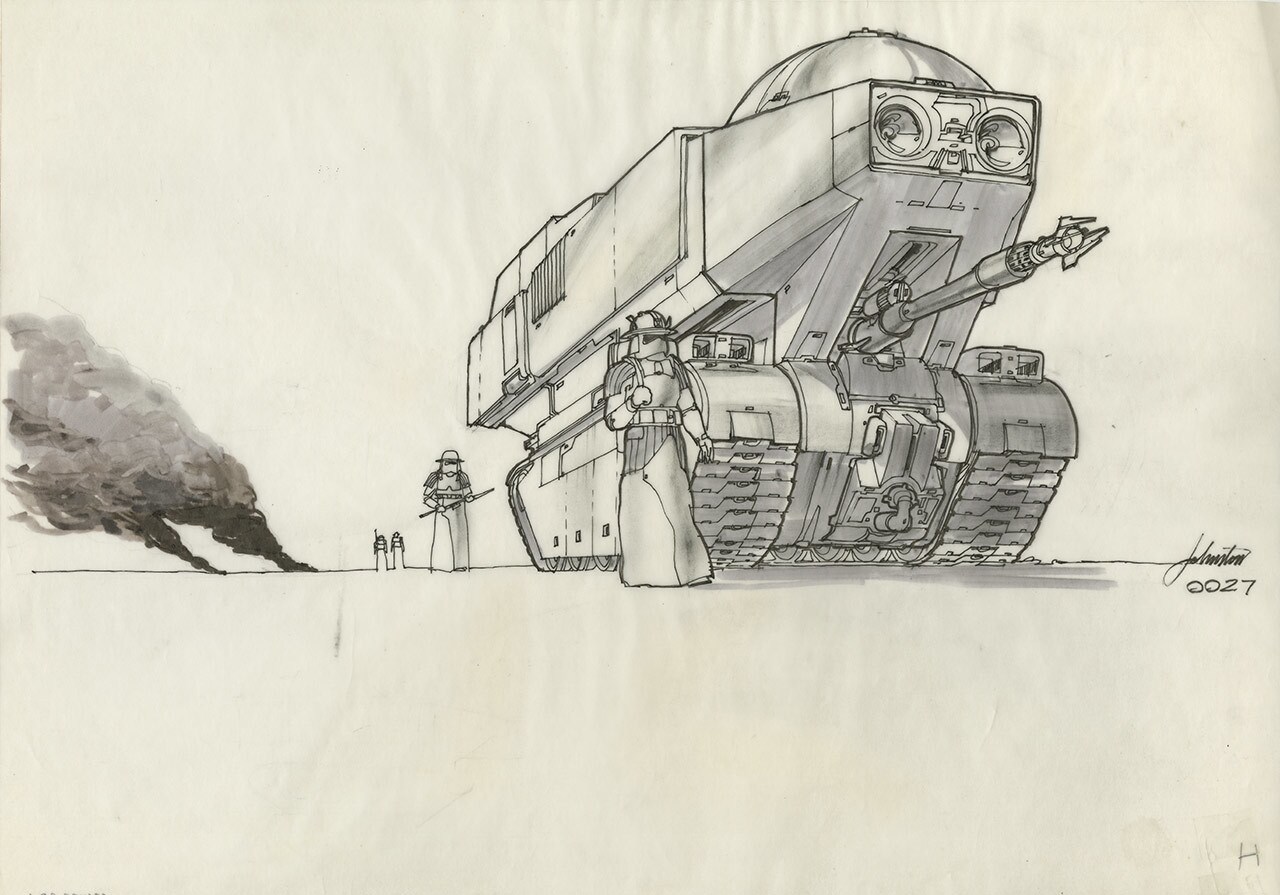

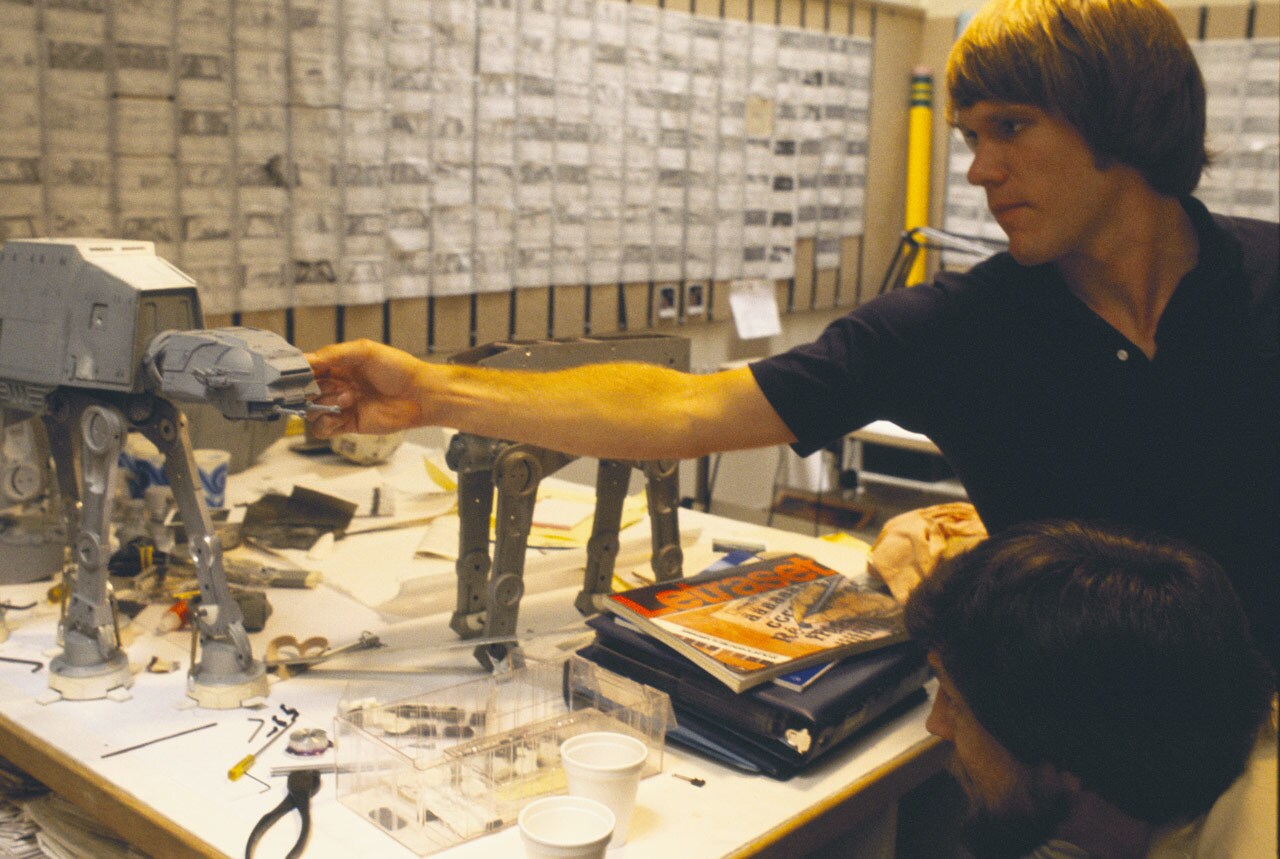

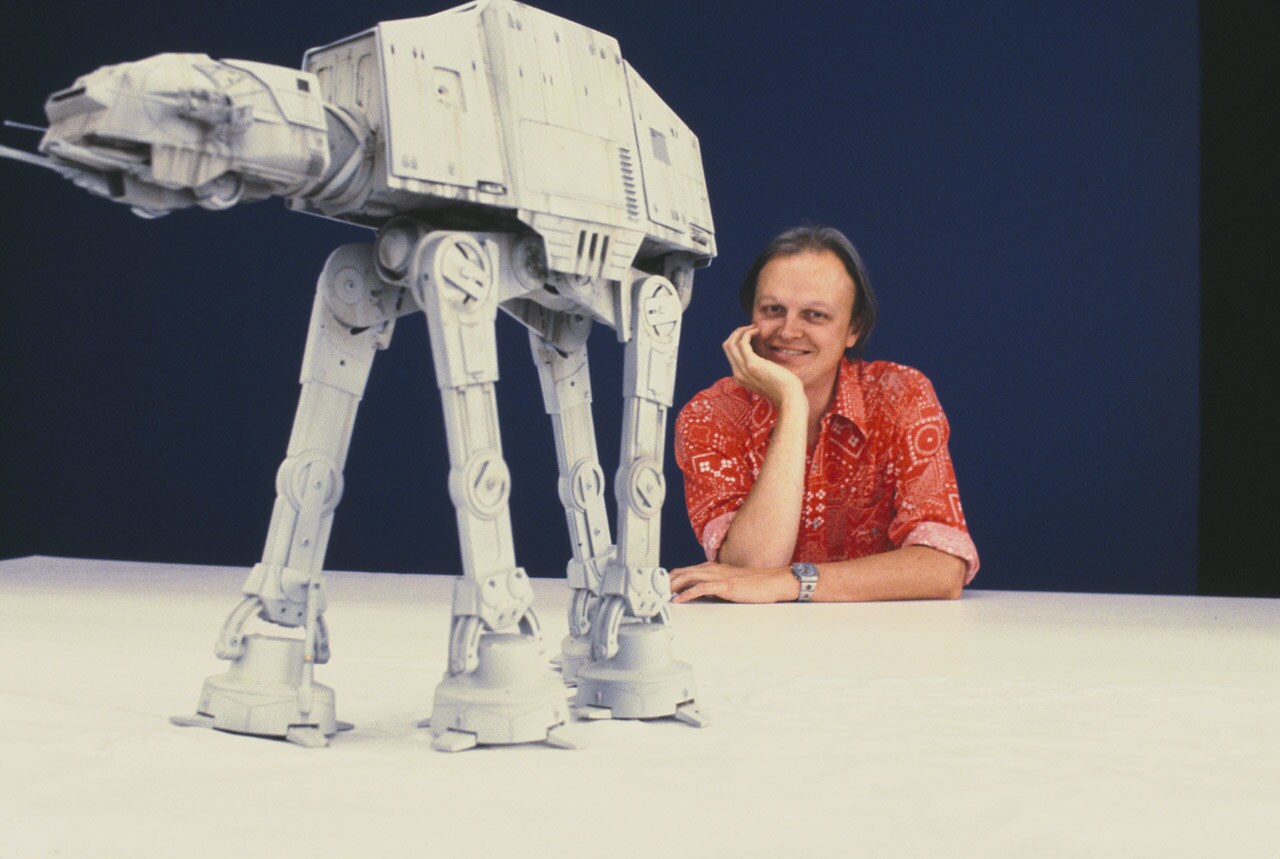

Following this process, Joe Johnston dialed in the look of the “Imperial tanks,” which evolved into something much bigger and other-worldly.

Joe Johnston: We moved to the new Kerner building. I had remembered from Cal State Long Beach, there was a portfolio that US Steel had published. It was all about, “This is how steel is going to be used in the future.” It was paintings by Syd Mead. They gave these portfolios -- I think there were 12 illustrations -- to design schools and students. They published them with no copyright at all. “What we’re saying is, this is the future.”

One of the illustrations in there was a truck that walked on four legs. The illustration of it was walking through this snowy forest and I thought, “That is really cool.” It was a truck, it looked like some kind of equipment hauling vehicle or something -- I don’t remember what the intended purpose of it was. But it was definitely a truck.

So I took the idea of this machine that walks on four legs and I made it, basically, a military vehicle with a separate head. As I remember it, the Syd Mead illustration was sort of all one piece. It was the truck body and sort of a cab up front. I don’t think it was a separate head. I took that and started working up designs using that basic idea of a tank that walks on four feet through the snow, and that became the snow walker.

We never referred to it as the AT-AT. We hated that name. [Laughs] We just called it the snow walker.

A popular myth is that the construction cranes decorating the bay in Oakland, California, served as inspiration for the walkers…

Joe Johnston: [Laughs] Yeah, I’ve heard it. I think that somebody just saw those cranes and said, “Hey, that looks just like those walkers in Star Wars!” But that’s total nonsense. I give more credit to Syd Mead than the Oakland port. [Laughs]

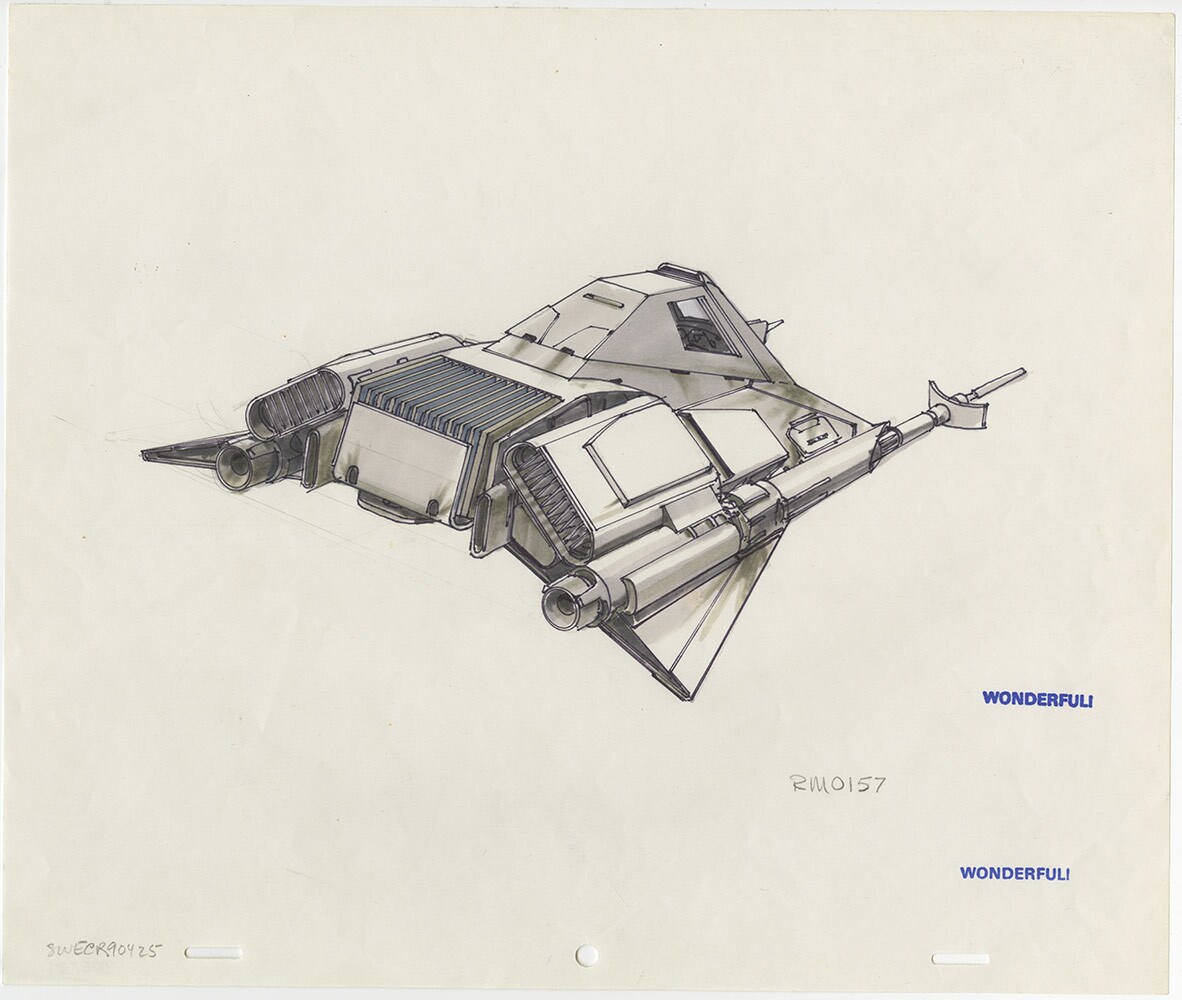

Next, the design team tackled the snowspeeders.

Joe Johnston: We were doing a lot of different designs for the snowspeeders at this point. One of the ideas was, what if they took the cockpit off of a Y-wing, for instance, and powered just the cockpit, and made a little speeder out of that? We actually built a prototype of that. It was Ralph who said, “If these rebels are having to build this stuff themselves, if they were building them from scratch, they would use all flat panels. They would just cut up some steel or whatever material the rebels had, and they would build these things out of flat panels.”

So Ralph did this design that was basically that. All the surfaces looked like they had been cut out of a flat piece of steel. That was really cool. I took Ralph’s design, and like we always did in the design process, I would do some sketches and send them back to Ralph, and Nilo [Rodis-Jamero] was doing stuff, and we just traded ideas back and forth until we finally came up with something that was close. We’d always get George’s approval, of course, on all the designs. Then once we had a basic, designed shape, we would start detailing it and deciding what the engines looked like and what the guns looked like and all that stuff. But we always started with what the basic shape is.

I would have to say that the original germ of an idea came from Ralph and his notion that the rebels didn’t have the facilities to create anything that had compound curves on it. They’re just welding stuff out of sheet steel. [Laughs] The final design was following those design rules.

“Let’s Just Do This the Way They Did in King Kong"

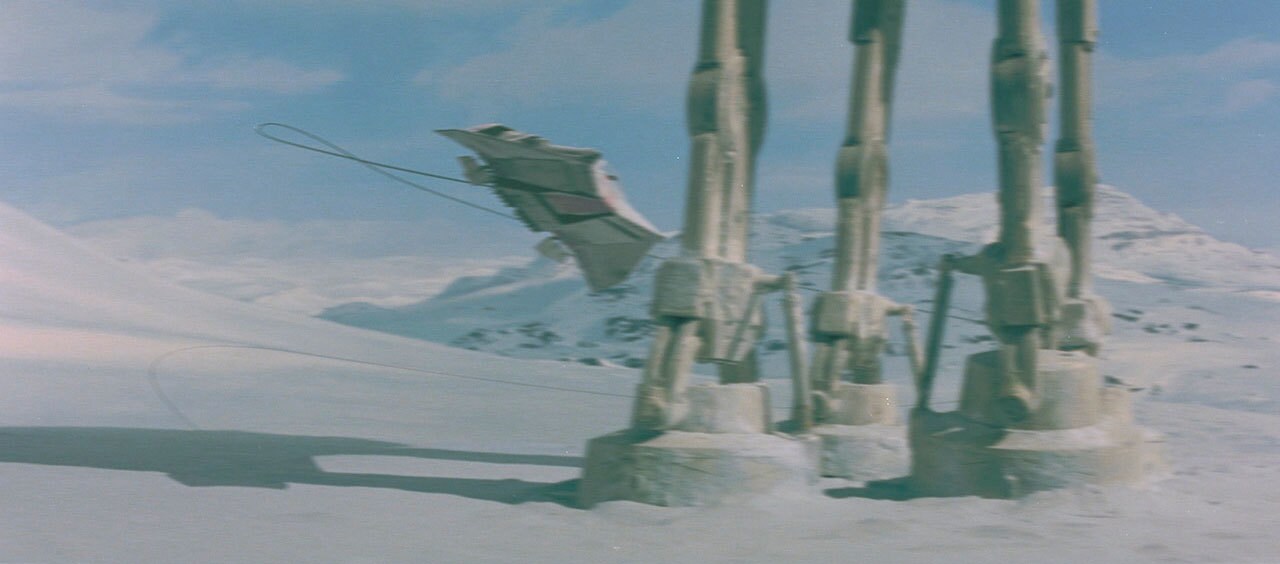

With the shots and the designs finalized, one question remained: how would they pull it off? Ultimately, the decision would be made to utilize stop motion animation for the walkers, in which animators move and shoot a miniature one frame at a time, with the snowspeeders superimposed later.

Joe Johnston: Once I showed George just the basic sketch of “what if we took this idea,” and he said, “That’s cool, I’ve never seen that before,” I knew that we could do it.

Phil Tippett: Dennis Muren had been brought on early, and he convinced George to do the walkers and the tauntaun with stop motion because there was more control.

Dennis Muren: Well, it seemed like it was going to be pretty daunting if you do it the traditional ILM way, in which everything was kind of blue screen… I thought that was just a really bad idea. There was talk about making a miniature self-walking mechanical walker, and I just said, “We can’t do that. That will never work, and based on our track record, it will never get done in time.” [Laughs] Maybe in time for the third movie or something, but forget that.

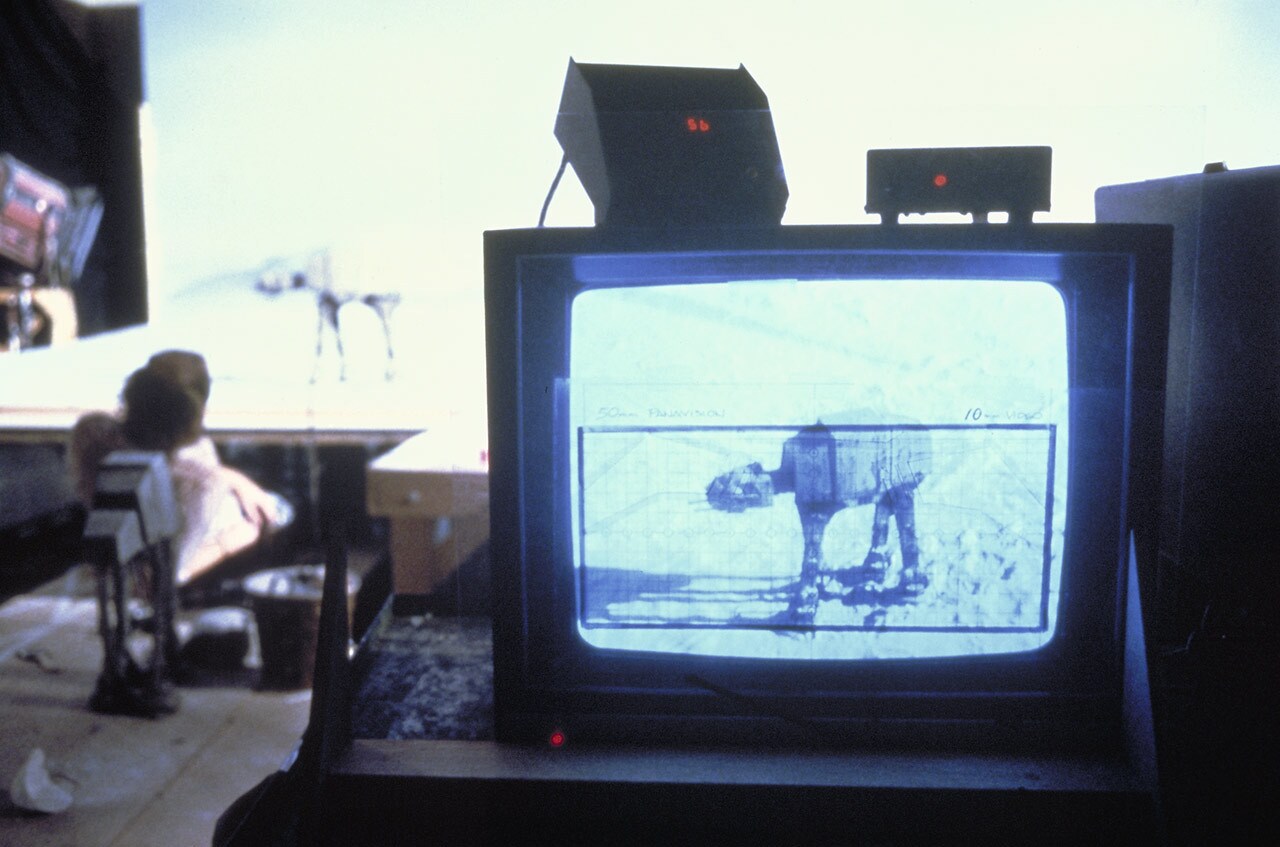

What I wanted to do was make sure that the thing looked totally real, and the way I’ve always done that in the past that I loved was to have it all viewable through the camera as a composite. My concern was the speeders; they were sort of flying by and they need motion blur. The way to do those was the good old Star Wars way [with the Dykstraflex, a computer-controlled camera system developed for Star Wars], and try to get the matte lines better, so we built some equipment to help on matting and everything, and the blue screen.

Joe Johnston: We showed it to Phil and [stop motion animator] Jon Berg, and Tom St. Amand was building the armatures at that point, and they got really excited about the idea of animating six of these things, or more, I forget how many we had. We only had three actual animation walkers, but we comped them into other shots so it looked like we had six or eight or 10. I forget how many you see in that opening shot.

I knew it was going to work. They knew they could do it. There was a lot of R&D still involved to make them walk and to make them look heavy and see how they moved and all that stuff, but we knew it was going to work.

Phil Tippett: [Stop motion]’s a process of taking an articulate model, or puppet as we call them, and putting them against some kind of a background or against blue screen, and incrementally move each of the joints, one frame at a time, and take a frame of that. We have these things called surface gauges that were used by [effects legend] Willis O'Brien as far back as 1925. They were a machinist tool, a pointer gauge they used to locate things, like on the lathe bed. O’Brien used those, and we carried on using those forever, pretty much until computer graphics came in.

We would put a pointer gauge on, sometimes two, sometimes three depending upon the registration. That allowed you to find a point on the puppet that you could move to or from, so you could gauge empirically the distance it was moving and keep things registered. So you just move from point to point to point, and make the movements bigger or smaller depending upon the acceleration or deceleration, and then remove those gauges and shoot one frame, then return the gauges and repeat the process until the shot was done.

Dennis Muren: I knew how to do that stuff, so I had a clear idea of doing it, and I knew Phil and Jon and all the animator guys. I thought this could be really neat. And also, this was just one sequence. [Laughs] “Okay, that one’s done, great, I trust everybody. I’m going to light it all. But then I gotta figure out how to do this asteroid sequence, and then I gotta figure out how to do this other stuff.” [Laughs]

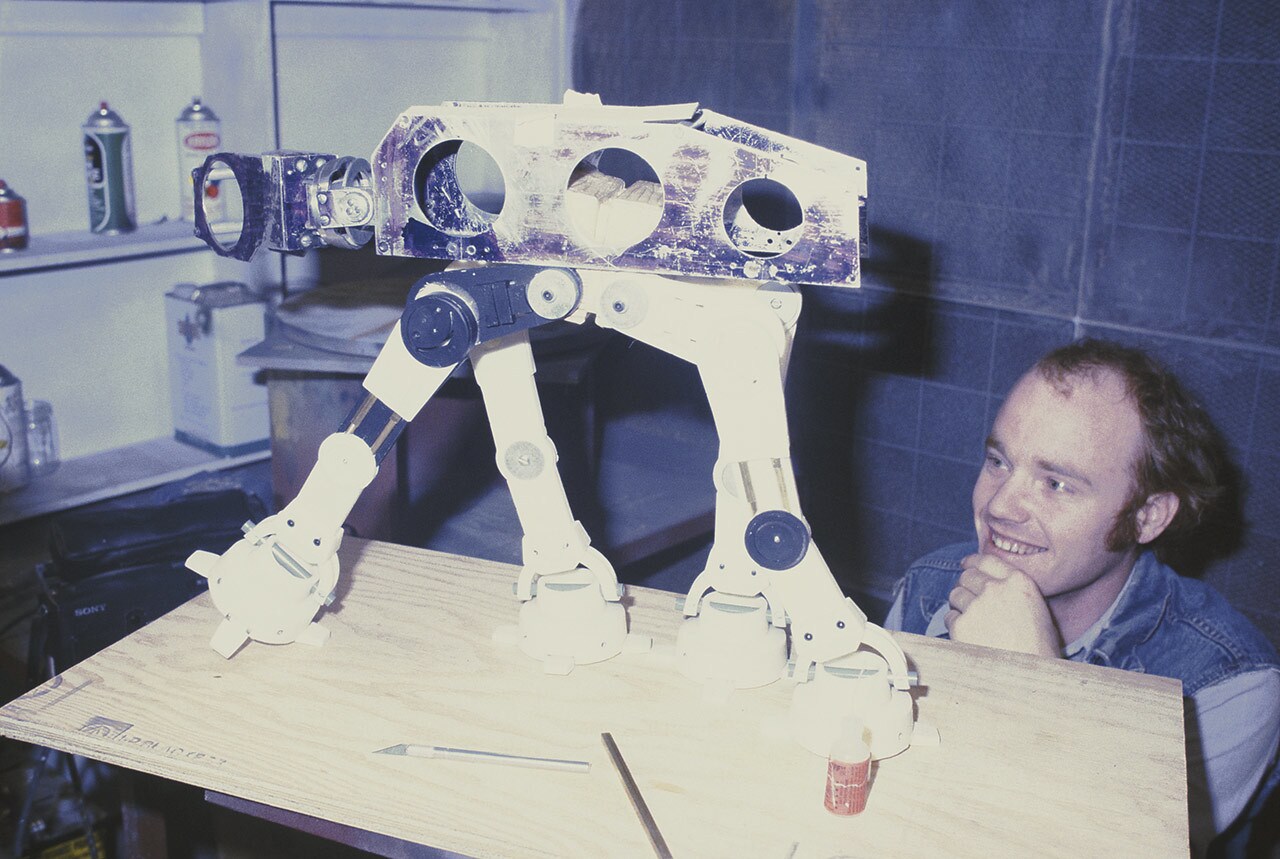

Phil Tippett: It was really cool, we were all really excited about it. Jon Berg had, by that time, created the prototype for the walker, and it was just very bare bones. It was pretty much just the legs and the carriage. We got the first reel-to-reel single-frame animations unit. I just spent a lot of time practicing.

The first thing we did was to go out to one of these wild animal farms and got an elephant, and I put chalk marks on all the elephant’s joints. We basically did it on Muybridge takes [Note: Eadweard Muybridge was a 19th century pioneer in early motion pictures whose photographic studies of animal locomotion proved highly influential to future generations of animators.] and it was shot on 35-millimeter film, and I would take that back and put it on the Moviola [film editing machine] and just study the footfall patterns.

So we did a few tests like that, and that didn’t work, because the walkers were like 100-feet-tall and the elephants were 12-feet-tall, and so the scale just didn’t match. So it took us, oh, I guess a number of weeks to figure out what the footfall pattern of the walkers would be, which would give them the proper scale.

Joe Johnston: It continued to evolve right up until we had to start making [the walkers], and we had to start casting them in resin and producing them. Just to say that there’s going to be a vehicle that walks through the snow is one thing, but to actually make it walk is a whole different thing. [Laughs] It wasn’t really until Phil Tippett and Jon Berg did these stop motion tests that we knew this is going to be really cool sequence.

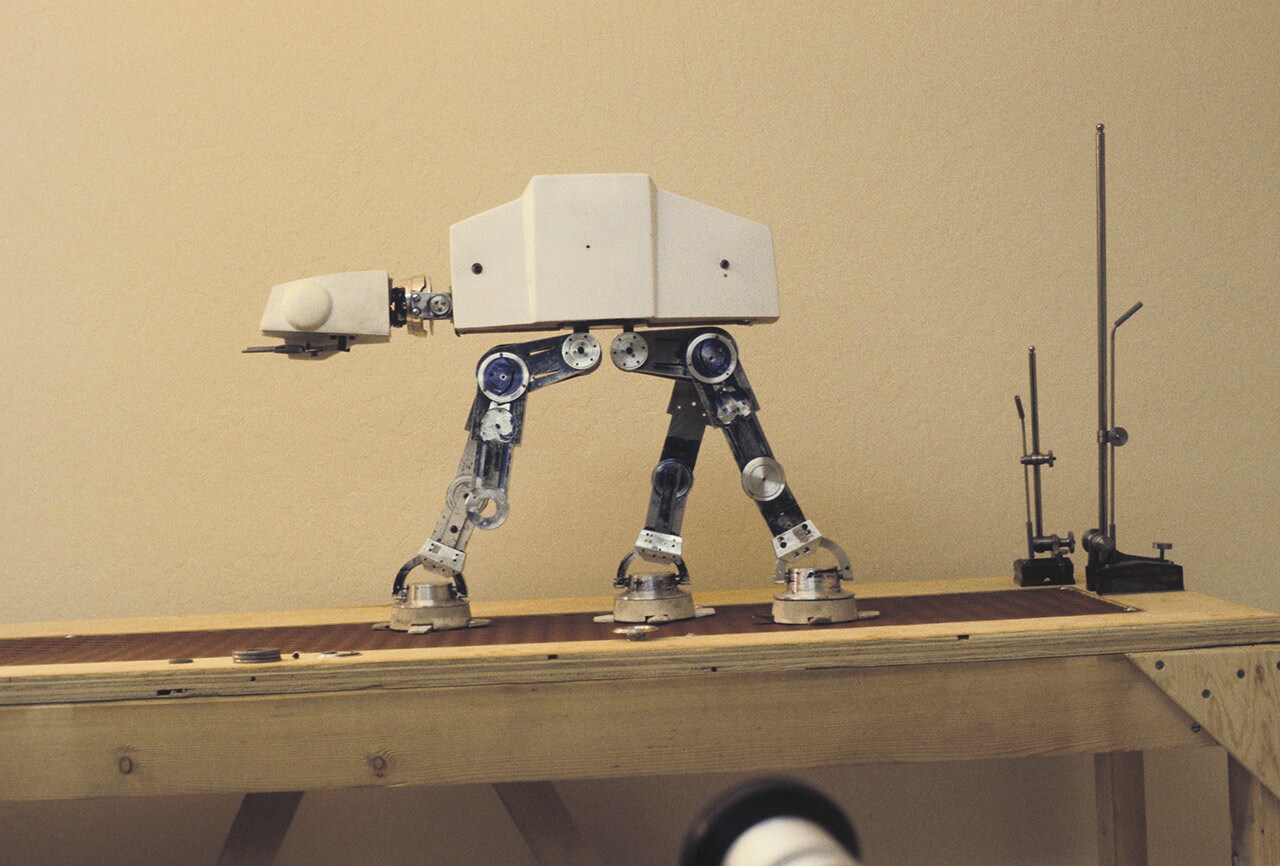

After completing the research phase and finishing the walker miniatures (there would be three total), Phil Tippett and the animators began to shoot the sequence.

Phil Tippett: They had to have three feet in contact with the ground all the time for stability. Only one foot could move at a time, and the increments were like, really tiny because the things needed to be lumbering and slow. Some of the movements were really invisible; you just had to feel, you couldn’t even gauge them. You just had to kinda feel them.

Dennis Muren: [The size of the miniatures is] really just based on how big someone’s hands are so you can get to the puppet to be able to move it. Jon and Phil were involved deeply in that. I think they figured out in the end, about 15 inches high. You got two leg joints in your hands maybe around four inches across, so that will give you eight inches, and you got a few more inches left for the body. Everything just kind of fits.

You’ve got to be able to animate that. With the quality we needed, it’s got to be really great animation. We’re going to have 70-millimeter prints out there, these shots are lingering, they’re not like fast action. There may be speeders flying but these things are moving slow. They’ve got to look real. And if there’s any little artifact, that’ll be okay. It will look kind of mechanical and that’s fine. So there’s no problem with that.

That’s really what it was based on. We had the sets that would open up and the animator could just [pop up]. There would be a part right in the middle, a little trap door. The guys would stand right up, Jon and them could just be right in front of it, easy access, not like hanging over something, but as comfortable as it could possibly be for the animators to get in to do their incredibly important job.

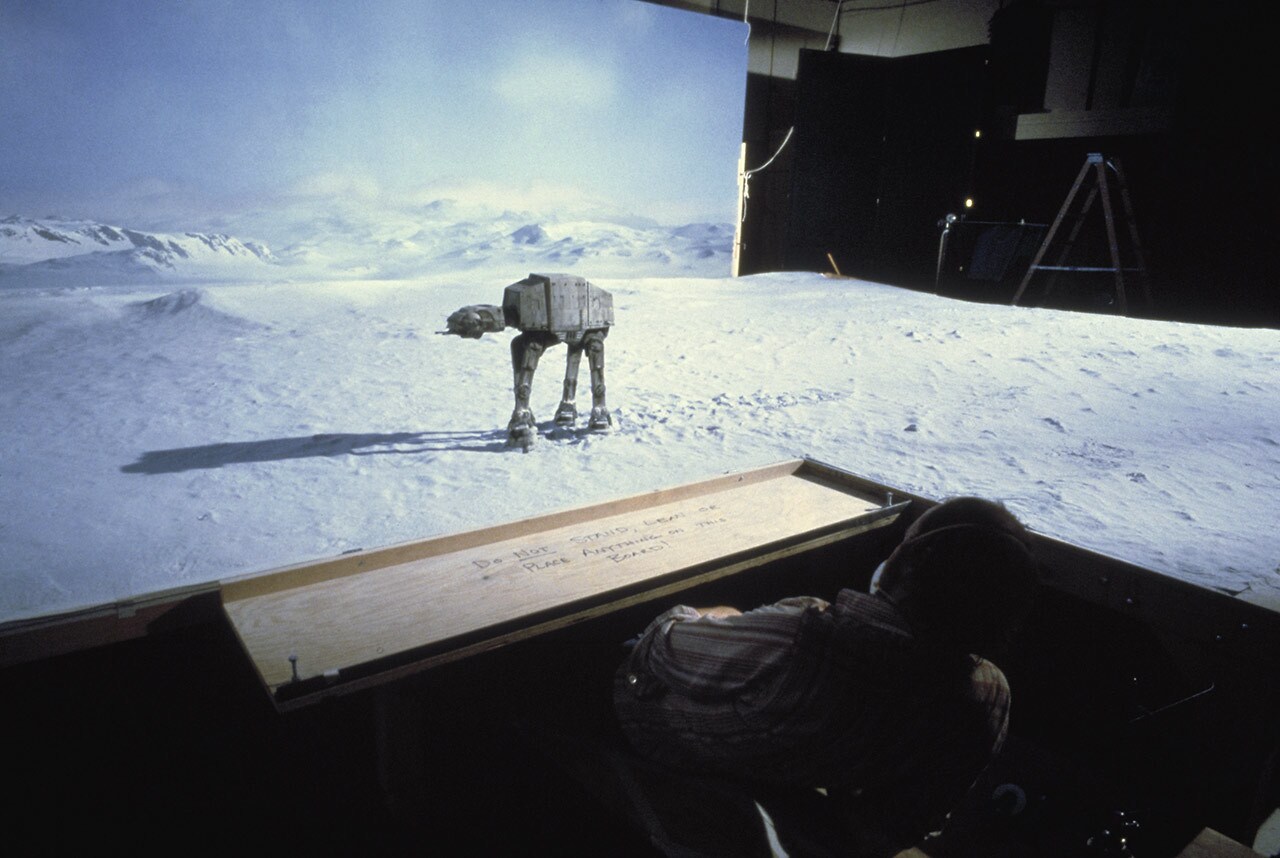

Phil Tippett: There were some problems right at the beginning, in that initially we were shooting the walkers against blue. Background plates would have been shot in Norway, and we were really limited by what we could do because for the blue-screen shots, we could pretty much only do locked-off shots, so Dennis came up with the idea of using miniatures and background paintings.

Dennis Muren: It was really the walkers, which are really terribly slow moving on the screen -- just looking at them in broad daylight and any little matte lines or lighting mismatches would kill it. So I said, “Let’s just do this the way they did in King Kong,” where it would be paintings on glass and big backdrops.

Phil Tippett: They found this kid, Mike Pangrazio, who was like a really brilliant painter, going into the matte department. He painted these huge background scenics of skies and mountain ranges in the background.

Nilo and I built a bunch of foreground sets with the stuff you do vacuforming with, and we would just get like, stage boxes, like apple boxes, and get heaters and heat the stuff up and press them down. Then [we] painted rocks into them and made foreground sets out of baking soda that kind of pushed the perspective back.

Most of those sets, since the baking soda was unstable, were in the foreground carefully aligned, and then the walkers were on plywood tables between the painting and the foreground pieces.

Dennis Muren: I put a big sheet of bridal veil, which is a thin material that they use for veils and for fabric, into the set. Twelve-feet-high by 20-feet-wide, to get a little sense of haze. It had to be stable over a period, like eight hours, while the animation was being done.

Joe Johnston: In the storyboards, it would always indicate that it’s firing at the snowspeeder or at the rebel base. They knew that at some time during the shot they needed to animate the guns, as well. I totally left those guys alone once they started animating because the process requires so much focus and so much attention to detail.

Phil, he preferred to animate at night when there was nobody there. He wanted to do his shots alone because he didn’t like to be disturbed. Because as you animate, you’re already thinking about what the next frame is going to be. It’s really a mental labor-intensive process, stop motion animation, so I tended to leave those guys alone.

Phil Tippett: We were all really committed. It was the chance of a lifetime, really. We were all super geeky over all of this stuff and now we had an opportunity to do this stuff. We were all young and had a lot of energy.

Dennis Muren: There was one shot, a sort of dark shot, when you’re looking at the heads of the walkers, like three of them. You’ll see a little window in the front of that walker head, and it’s red inside. And we were going to have those be red inside there in every shot, and I don’t remember what happened, but we never did it again, except that one shot. We thought it would look kind of neat, and maybe because it was an overhead shot, I remember, maybe we added that later on so you could sort of see something fresh on it. Or maybe nobody even cared so we didn’t do it the other times, I can’t remember. But we were always trying to find another way to top ourselves.

Phil Tippett: Well, if a shot worked, it worked, and we built it one shot at a time. It’s like laying bricks, you know? You just keep doing shots until you’re done and the scene worked. Then when Ben Burtt gets a hold of it and you see the first answer print, it all comes together as one thing.

[I worked on the Battle of Hoth sequence] maybe three or four months? Maybe a little longer?

Joe Johnston: I remember seeing shots, because we would have dailies every day of what the animators had shot the night before or the day before. So we were seeing the shots that it was going to be in. By the time I saw the final sequence, I pretty much knew what it was going to be. But the first time we saw an actual, fully finished, detailed walker, walking on a baking-soda snow field, I’m sure the [crew] audience had a round of applause for the animators because it was pretty stunning stuff, to see this thing move for the first time.

Dennis Muren: The speeders were shot as a separate element. And then the background plates, flying over, were shot in Norway, the airplane and helicopter stuff, and the cockpits were shot also on a blue screen in England.

George Lucas: The basic thing we learned was that the Dykstraflex, which was a sort of horizontal animation platform, allowed us to shoot models in soft frame. And as a result, we could actually do the movie. A lot of these things, in terms of visual effects, you just couldn’t do those things [before Star Wars]. Nobody had ever done them before and you didn’t have the equipment, you know? It hadn’t been invented yet. So, on A New Hope, we invented a lot of the technology. And the guys that were working at ILM were learning how to make that kind of a movie. Because you look at the movies that were before Star Wars and then the movies that were after Star Wars, there’s a big difference in terms of visual effects. And the greatest visual effects film made at that point was 2001. And they didn’t have to pan the ships and they didn’t do any stop motion. So it was very different kind of movies that were made then. And I wanted something that was very fast, where the shots were very short, but where in space they were traveling all around and you could pan and do things like that. You could pan on 2001 but it was very, very slow. We carried that kinetic energy from Episode IV to Episode V, where you could pan with things, things would move fast, and you get a more naturalistic feel to the movie.

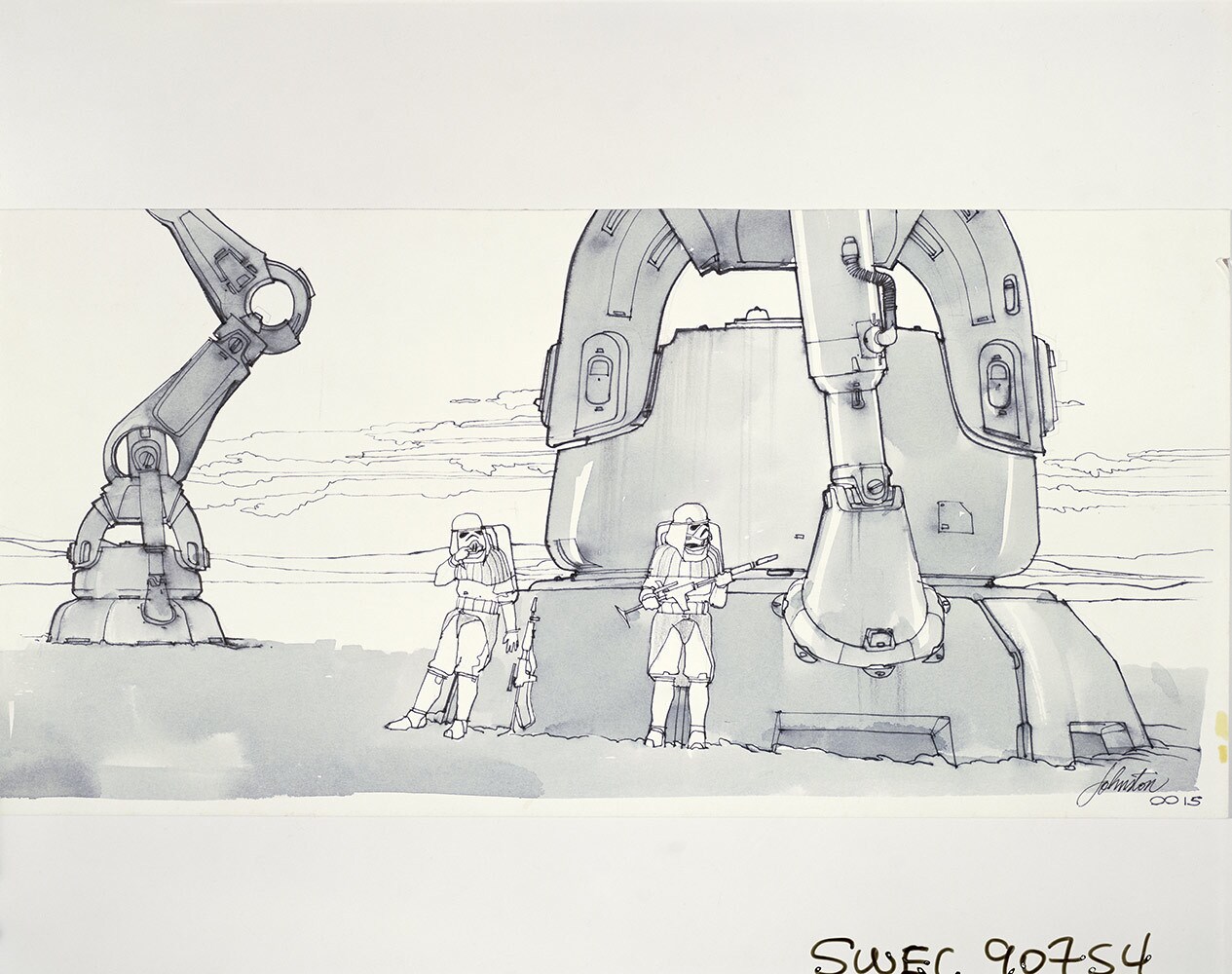

The sequence also features a cameo by a smaller walker – dubbed the “chicken walker” by Joe Johnston, and later officially christened an AT-ST.

Joe Johnston: In the process of designing the four-legged walker, I was looking at a lot of reference on military vehicles so I could familiarize myself with the textures, the way parts are put together, and how a lot of stuff is built at an angle so the bullets would bounce off, stuff like that.

One thing I noticed was that there’s always, with any militarized force, there’s the tanks, then there’s the support vehicles, there’s the troop carriers, and there’s the scout car, and there’s the guy in the motorcycle. And all we had were the walkers. I remember thinking, “Wouldn’t it be cool if the walkers had the little scout that could go out ahead of them [Laughs] for whatever reason. We’d put guns on it so it could defend itself.” That’s sort of where the idea came from -- in order to be realistic with an armed force you need the scout car, as well.

In creating the chicken walker, however, Joe Johnston didn’t follow his usual process.

Joe Johnston: It’s one of the models that was designed through kit bashing. I didn’t do any drawings of it before I had a three-dimensional model of it. I just used model kits and planes and there was a model by -- I forget the company name, it was a bulldozer. It had a lot of great parts.

I basically was making the prototype and making it in three-dimensional form instead of doing sketches first. I finished the model, I showed George, he liked the design a lot. He said, “That’s great, but we don’t have any time.” This was very near the end of the VFX process, so we didn’t know how we were actually going to have time to get this thing into any shot in the movie. But George says, “You know, we’ll use it in the sequel. We’ll use it in the next film,” which at the time was called Revenge of the Jedi.

So Phil Tippett came in and said, “What if I took the model?” The three-dimensional prototype, which was just a static model. All it did was just sort of stand there. He said, “What if I took the model, took it apart, and attached the pieces to a stop motion armature? We can build an armature super-fast because it was just basically these aluminum arms.” He said, “I think we’ll have time to get it into a few shots.”

So he did that. He basically destroyed the model but then reattached all the pieces to this armature. He was able to get it into one shot in the background, where it’s just sort of cruising through. [Laughs] That’s the only shot we had time to get it into.

Here, Phil Tippett discusses some of his favorite animations from the sequence.

Phil Tippett: There’s a shot with three walkers in it, and it took three animators to do it. I animated the foreground walker, Jon the midground walker, and Doug Beswick the background walker. We’re pretty much looking at the walkers in profile walking, right to left.

You never know what you’re going to get until you see dailies the next day, and the video cameras didn’t do any good other than testing things, because you’re not looking at it from exactly the right angle through the lens. So you just don’t know until dailies the next day. So that turned out really good. I was happy with the timing.

And there’s another shot, I think there’s two walkers, and it’s like a close-up of their heads. Jon and I were shooting, and I think he had the walker on the right and I had the walker on the left. They’re kind of coming at you relentlessly, and just in the middle of the shot I just decided, I wasn’t even thinking, to turn my walker’s head so that it looked into the lens. It was really effective. It made the shot a lot more creepy. You work intuitively a lot.

Sound Story

Following completion of post-production, combining the stop motion animation with the composite and live-action elements, it came time to add sound. Here, sound designer Ben Burtt discusses his work for the AT-ATs.

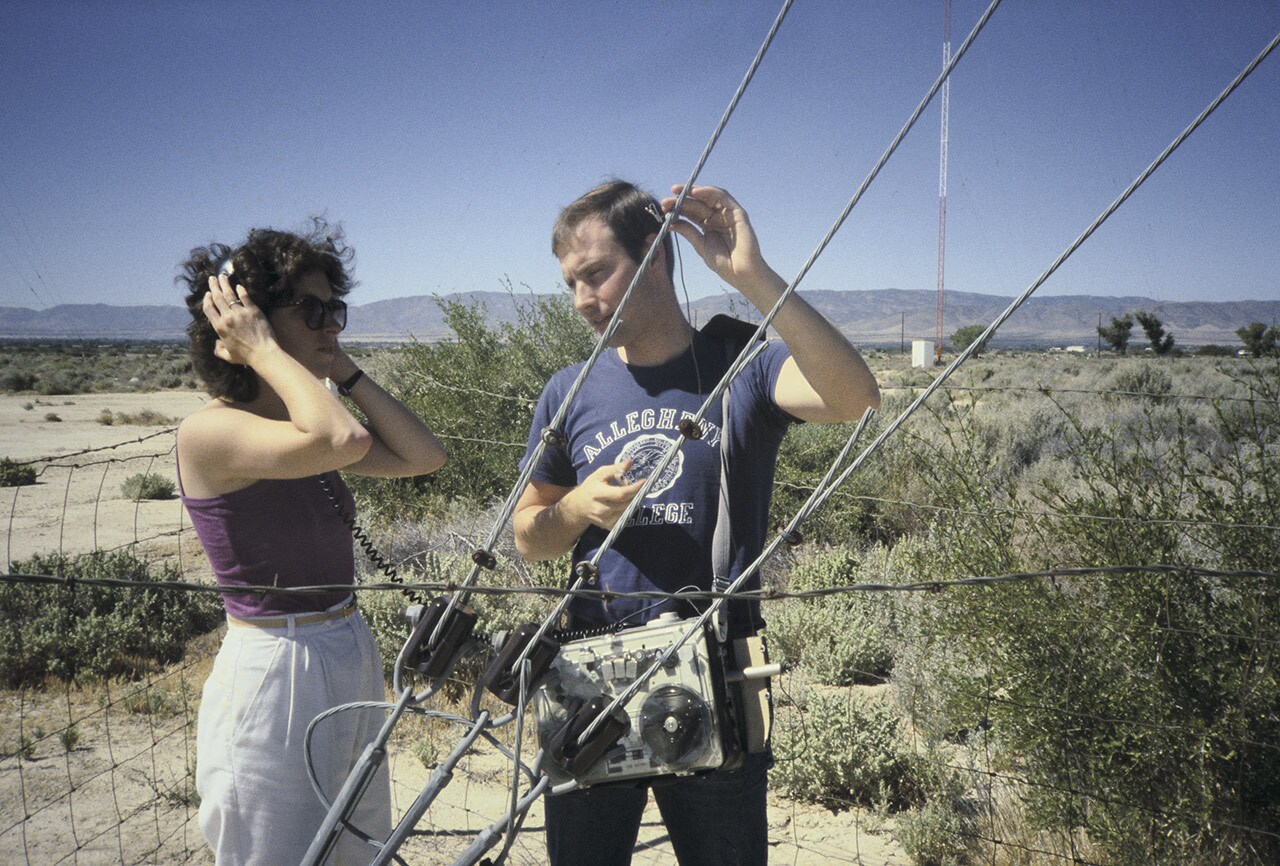

Ben Burtt: I gathered a lot of sounds for the walkers, and that was a particular focus of mine. Of course, there were many different things. There were the metallic sounds of the squeaking joints, and they were pretty much the dumpster in front of my house. It’s the sound I’d hear when I’d go out and throw the trash away. “Open the lid, [squeaks and groans].” I thought I’d go out there and get that.

There was the stamping of the feet and the rhythmic sound of the engines, and that really came from two different sources. I think Randy [Thom] recorded the elements for both. One was the metal shearing machines. A place in Oakland, there was machinery, it was a place where a sheet of metal comes down a conveyor belt and then it would get stamped, knocked into different shapes, or embossed with a pattern for whatever the product was. [Makes a clunking sound.] It was a big stamp. And Randy started recording those, and we sent him back a second time. There was a nice variation of heavy stamping that had some clickety-clacks to it. That was a great element, and set that aside.

There was the knee squeak, there was the stamping sounds, and there were variations of that. The actual weight of the foot [fwoomp! fwoomp! fwoomp!] was an artillery explosion that was recorded in Oklahoma. A real artillery explosion, and I went to a shooting range there where they fired at me from five miles away, and they were actual high-explosive shells. It was the real thing. I was with a guy called “a spotter,” it was a soldier with a radio and he’s telling them whether they’re near the target or not. So there’s a target out, maybe two or three hundred yards out in front of me, and we’re in a trench.

I put my microphones out there on a long cable, ran it all the way back, and then got down in the trench with this soldier. He’s wearing a helmet -- that’s right, they did give me a helmet! We’re out of direct line but they would fire at us from five miles away. You’d hear the shell coming, you’d hear the distant thump of the firing of the shot, and then a moment later there was this -- it sounded like a jet plane coming through the sky and that was the artillery shell. And then it would explode out there and send shrapnel everywhere, [it would] come pinging and zapping around. Great recordings, by the way.

A real artillery shell makes a [whoomp] sound. It’s not a “kaboom” like you’d think, necessarily, it’s a [whoomp!], like that. The pressure goes up in your ears and you feel the vibration. That [whoomp!] of the 155-millimeter Howitzers was used for the actual step of the feet. It was this nice, heavy, low-end, unusual sound. We’d time it such that you had the metal [shink-ka-chunk, womp, ka-chunk, womp], you know, like that. You’d build it up and that sort of thing.

There were other motors in there of the walkers raising the leg and lowering the leg. The motor there is a tank turret, which I also recorded on the same army trips. I was with a tank group for a while, riding around -- the turret motors [whirrs], when it would turn, I recorded that. It became this mixture of a whole bunch of different pieces.

Initially what I did is I took all these different pieces and I made loops of them on film, on magnetic film. We could put them up on a string of dubbers, play them all back together, and then I could listen to these parts repeating. I could adjust the lengths of the loops until I got a fun, rhythmic [ka-kloom, ka-ka-kloom], you know? [boom-boom-king!] An orchestration.

And I’d record those different orchestrations, go in and adjust the length of something and then do another recording. And that way, just by trial and error, end up with something that was the most interesting and appealing.

This is a lot of detail but that’s the kind of stuff that you go through to come up with the walking cycles, as we call them, of the different walkers.

Looking Back

Forty years later, the Battle of Hoth may be the most iconic Star Wars battle scene, if not one of the most iconic battles in movie history.

Dennis Muren: Well, I mean, I can’t see it. Other people see it, but I know too much about it. I think part of it is, it’s such a mismatch of the armies. Soldiers out there with rifles and guns, essentially, and you’ve got these big armored things that look like there’s no way of beating them, and for Star Wars it’s such a spectacle and surprise, being out in the snow. Just making this happen. It’s just so open, the idea’s so open. There’s the little speeder things, like gnats, trying to hurt these things, and it’s hard for them to do anything and find the weak link, with the tossing the bomb underneath one of the legs and causing it to blow up, or wrapping the cable around it. You know, the little guys are clever.

Joe Johnston: It’s definitely the David and Goliath story in the Battle of Hoth, with the rebels and their little -- they almost look like insects flying around these giant walking machines. That’s exactly the idea.

Dennis Muren: I don’t know how to explain this, but it’s what the whole movie is when it’s together. At every moment it’s got input that has nothing to do with the effects. It’s all overlaid on to the final movie, and it has to be able to figure into to this moment: what the sound effects are at this moment, what the cutting is at this moment… Cut back to see somebody in the walkers reacting to something going wrong. There’s choices. Every cut is a choice.

And this sequence, because it’s a slower pace, you can get into those wonderful ideas and complexity that make good movies. Good movies have those things all the time. I think you can look at the difference between Star Wars and any sort of adventure space movie that was done afterwards, and you don’t know exactly what the difference is, but it’s things like that. The filmmakers are keeping it entertaining from moment to moment and they have pace, and it’s not just filled with explosions, effects, loud music. Not that. Swear words, not that. It’s all these emotions are mixing. It’s really hard to make a good movie. It’s really hard to do it.

I think that sequence brings all that stuff together, with effects.

And with The Empire Strikes Back celebrating its 40th anniversary, George Lucas, Ben Burtt, Joe Johnston, Dennis Muren, and Phil Tippett reflect on the film and their work on Star Wars as a whole.

George Lucas: Even though it’s an homage to ‘40s movies and a space opera -- where the characters are pretty cardboard -- I worked very hard to create the characters that would be iconic in their own way, and still be true to the classic adventure cinema.

Phil Tippett: A lot of people call that period kind of the renaissance of that kind of approach to filmmaking. It was a resurgence of how they made pictures in the ‘20s, ‘30s, ‘40s, ‘50s, really. I liken it to the Wild West. By that time, it was like the studios just didn’t understand how this stuff could go together. They’d kind of forgotten how to build the pyramids. George and [Steven] Spielberg and these guys studied all that stuff just like we did, and knew what the potential was for putting spectacle in the movies.

Joe Johnston: I don’t want to specifically pick out Empire Strikes Back, although I agree it’s perceived as the favorite. The original trilogy changed almost everything about the film business. It changed the way we look at movies, it changed the way we market movies, it changed the way we market everything after the movie comes out.

I’m not absolutely sure about this, but I think that Star Wars was the first movie where everyone who worked on it got credit, got screen credit in the end titles. If not, it’s the one that’s the most recognizable. George just wanted to do that. He wanted to give everybody credit.

He was such a generous guy. He took a [royalty] point on Star Wars and divided it eight ways and gave eight of us an eighth of a point. When I started working on Star Wars, I was making 300 dollars a week, which you could live comfortably on in 1975. By the end, I was thinking, “Wow, [Laughs] I’m going to go buy a house!” He did the same thing on Empire.

George didn’t have to do that. He wanted to reward the people who had made this thing possible and made his success possible. I think that working on the original trilogy was such a privilege to be a part of the thing it is now. Who doesn’t know what Star Wars is? It’s changed popular culture.

Phil Tippett: Well, I think most people are in agreement, it’s the best or most aesthetically pleasing of the first three Star Wars movies. We just felt really lucky to have been involved with the thing. George would stop by when we were working on stuff and put his eyes on it, and we would ask him questions about what he wanted. A lot of times he’d just say, “You guys know what you’re doing. [Laughs] Do it.”

Dennis Muren: Well, it was so big, and at that specific time it was definitely the hardest movie I ever worked on. I don’t know, I feel the same way I think everybody feels. It takes you to new places all the time. It doesn’t feel like it tried to copy anything else.

[Lucas] had such fresh ideas for that film. Hoth, and asteroids, and Cloud City.

The ideas were great -- what everybody came with, but especially him. It was just an amazing, amazing project, and so hard, but amazing.

Ben Burtt: It was all-consuming, and I was still young enough in my career that that seemed okay -- making a sacrifice because this is really exciting. But then you realize, can I do this for 20 years? Will I make it?

That aside, there’s some favorite sounds -- overall, the mix that we got on the film, the relationship between sound effects and music and the use of sound effects was one of our better achievements. We had learned a lot on Star Wars by seeing how easily dense dialog, music, and sound effects collided and become a big mess. Our new approach on Empire was to carefully construct and orchestrate those elements so each can have its greatest dramatic value. The mix had to be, ultimately, a subtractive process. You can’t hear everything going on at each moment, you have to be selective.

On Empire we really got going in terms of feeling professionally competent about the audio layout and how to approach it. That set in motion our pattern for the next 20 years, really. How we would prep for the film, what we expected out of ourselves and our crew, and the way we would do it. It was great. It really gave us a rulebook.

But from an aesthetic standpoint, I really love that film. There are some great moments in it: the carbon-freezing chamber, the snow battle, Dagobah, those are all fun moments. The sword fight between Vader and Luke, especially, there’s this whole section without any music. We were riding high then, I think, and we did a good job.

Joe Johnston: I feel very privileged to have been a part of the entire original trilogy. I wasn’t the best qualified person for the job by any means, but I think that I evolved in the process of working on these three films. George definitely made a filmmaker out of me.

When I took the job, I had no intention of ending up in a career like this. It was only through George’s -- not only the fact that he sent me to film school [Note: Lucas paid for Johnston to attend USC.], but the fact that he encouraged me to try things. He was very generous with his knowledge. Just sitting in the cutting room with George and going through the movie while he added shots and subtracted shots, and asked for storyboards and stuff, that’s like a semester of film school.

The thought that I had the privilege of doing that with him is still one of the things that -- I really cherish the memory of that, that whole process and all those years of working with him. It’s something that will always be the centerpiece of my experience in film. Even though I went off to direct films after that, the part of my career that I remember with the most fondness is the years I worked with George. It was a great time.

I was a kid, I was 25 years old when I started, and George was 31. He was a kid himself. [Laughs] It was a time of such amazing creativity from everyone. It was a time of experimentation and the it was the kind of environment where you could try anything. It might work, it might fail. We really didn’t know what we were doing on Star Wars. We had a better idea of it on Empire, and we finally figured it out on Jedi.

Dennis Muren: [Empire]’s definitely my favorite Star Wars movie. I was shocked when I saw it. I’m really proud of the little bit I had to do with it. It’s pretty neat.

But I’ve worked on a lot of big films, and at the end they’re work, and you work really hard to do them. You know, I’ve been making films since I was a kid. This isn’t going to hit me, like, “Oh my God, I finally made it,” whatever that is, that isn’t even something I would ever care about. But being able to work on a film with that big a scale and yet is perfect down into the minutiae of every department, is a very rare thing. I was aware of that, very aware. I’ve become more aware of that since then. Everything was just clicking on that show. I’m really proud of it and everybody who worked on it.