The cinematography lighting & VFX director tells StarWars.com about utilizing filmmaking tricks like rear projection to give the animated series an artistic flair.

In “Spoils of War,” the Lucasfilm Animation team crafted a memorable cold open for the second season premiere of Star Wars: The Bad Batch. It’s a peaceful and sunny day on the tropical planet Aynaboni until a swarm of menacing crab creatures roar down a picturesque beach, chasing three members of Clone Force 99.

For Joel Aron, the cinematography lighting & VFX director — a longtime member of the animation team and, before that, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), — the beach chase was yet another exciting challenge at fooling the audience. “It’s funny how different questions come up with a sequence like that,” he tells StarWars.com. “Someone says, ‘Do we need the characters to run in the water? Can they run on the beach?’ Having the characters run in the water like that can be challenging and expensive, but we find interesting ways to do it.” In this case, their feet stay below frame and animators add splashes at the bottom, a suggestion of the action.

The Bad Batch has been no stranger to water effects, since the first season took viewers to Tipoca City on Kamino. It’s always a challenge, as Aron admits, but one that he excels at by drawing on his past experience at ILM. “Stop thinking about doing it for real,” he says. “We just have to fool the audience, and they’ll believe it. The sound design will take it home. Back on my first movie at ILM, Hook [1991], an artist named Steve Price told me, ‘Whenever you’re doing VFX shot work, you have to play the sound in your head.’ I still do that. In our reviews I’m making sound effects as we watch. When we’re doing something like water, it’s all visual trickery. And this goes back to the practical era of visual effects.”

Not only does Aron constantly refer to his ILM experiences in his work, but also to the many series created by Lucasfilm Animation, beginning with Star Wars: The Clone Wars. From one to the next, the team has been improving their techniques, each innovation snow-balling into the beautifully realized half-hour episodes of The Bad Batch. “When we were starting Bad Batch, we were finishing the last season of The Clone Wars, and there was also overlap with Tales of the Jedi,” Aron notes. “We’re pushing the limits of what we can do within our sandbox to make this show. Our timeline to make one episode hasn’t changed since Clone Wars. We have a matter of weeks to complete all the lighting, mattes, and VFX. At the same time, there are multiple episodes in progress, and we don’t stop between the seasons. We keep going.”

The constant schedule of turning over shots — now for simultaneous productions — has allowed the artists to find their groove, as Aron explains. “The schedule feels normal,” he goes on. “We’ve learned we can do it. Working with both [Taiwanese partner studio] CGCG, Inc. and our team here, we’ve found areas where we can crank up the volume. We were pushing hard at the end of Clone Wars. In all of those episodes with Maul and Ahsoka, we were trying to see how cinematic we could make it feel.”

That approach carried over into both Tales and Bad Batch. It was on the former that Aron initially chose to implement an anamorphic lensing style. This wide-screen format is taken directly from traditional live-action films (such as Lucasfilm’s first production, American Graffiti [1973]) and allows for a refined depth of field and ability to artificially add layers of film grain. Those innovations, first used on Tales, were then quickly adapted for Bad Batch.

“There’s even more progress that you’ll see later in the [second] season,” Aron says. “As George Lucas said back on Clone Wars, you need to be able to stop on any frame in any episode and have it look like a still painting or something right off the big screen. George said, ‘We’re not making this for Blu-rays and DVDs, we’re making this for people who like to see things in the cinema.’ We haven’t stopped doing that. We keep pushing.”

It's something Aron first learned from the innovators at ILM. “I spent the better part of 17 years trying to make things look photo-real to fit into a live-action visual effects shot,” he explains. “Working on movies like The Perfect Storm [2000] and Pearl Harbor [2001], you had to immerse yourself in that type of filmmaking to make sure that you could produce CG content on that cinematic level. Jurassic Park [1993] only had 50-some CG effects shots, but they all connect with the audience. Things were crafted by hand. There was no auto-rotoscoping to blend elements together. There was a quality of the filmmaking that allowed the simplicity of the effects to hide within it.”

An earlier advancement that influenced the techniques currently used for The Bad Batch came on Star Wars Rebels, the first production the team made without George Lucas’ direct supervision. To Aron, the look of The Clone Wars was still “too CG.” As a demonstration, he took a shot of Yoda from The Clone Wars, and began adding layers typically used only by live-action visual effects artists. “When you have a digital T-rex against a live-action shot, the edge of that T-rex can’t be sharp,” says Aron. “There’s a blur that makes it look like it’s there. So I took that same method into Rebels. That show has a sizzle all around the edges. There was contrast. I wanted to rip up the edges all the time.” Animators routinely began applying grain in the final color grade. “Now we do it in everything.” He smiles as he talks about this “cinema first” principle, noting that “we still keep the fingerprints of the classic George Lucas style in there.”

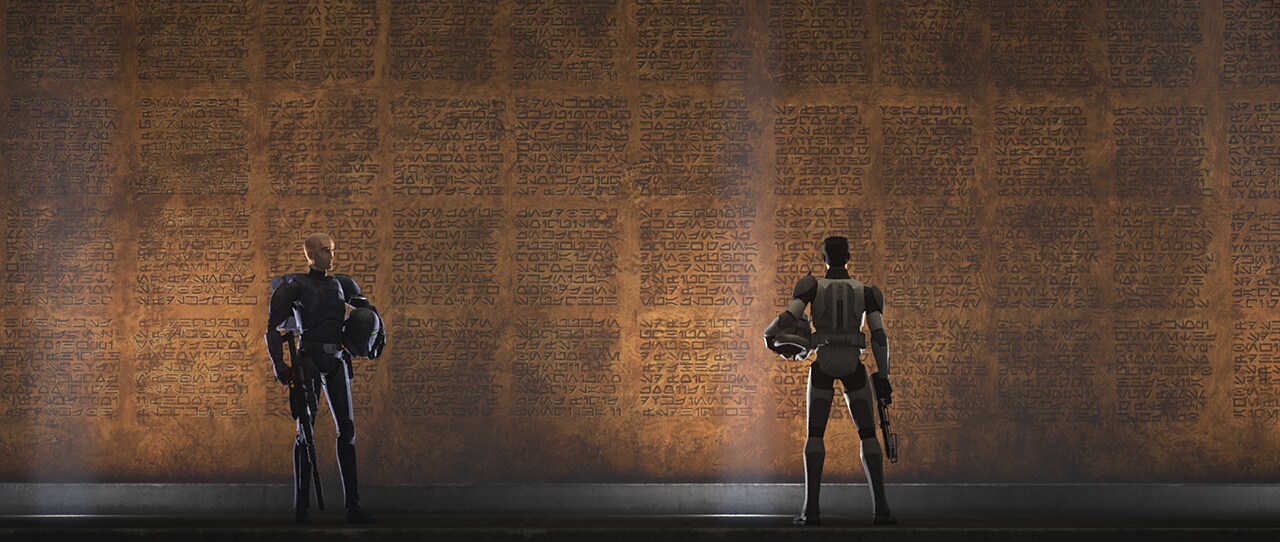

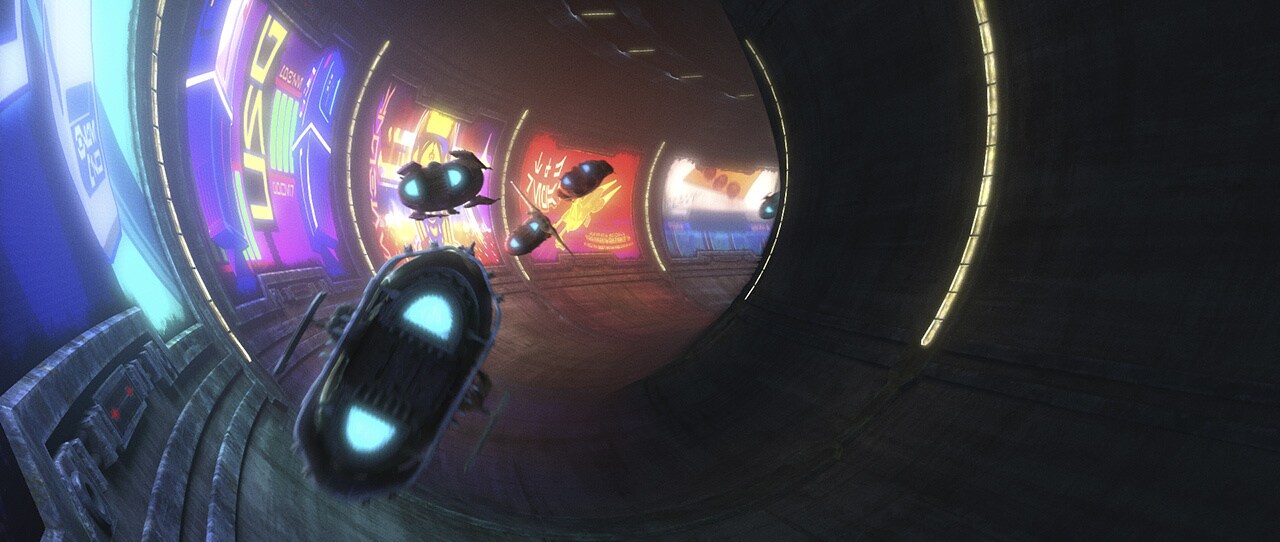

One ingenious idea came to Aron as the team worked on the recent Bad Batch episode, “Faster,” featuring the fast-paced sport of riot racing. “I had a crazy idea to pull off the racing episode,” Aron says with glee. “We were looking at building a huge set that was going to be really expensive. But what if we built a track and I race a virtual-reality camera down that track in CG?” If one thinks of the computer-generated setting as a physical space, Aron then placed a digital camera that captured images at 360-degrees within that environment. Moving the camera through the racecourse, he’d capture the scene’s background in motion. The team wouldn’t need to animate all of the speeders physically racing through a massive set, but instead simply place them in front of the moving background.

“When the race is happening, the ships aren’t moving in a lot of the shots, but the environment looks like it is,” Aron explains. “It’s like rear projection! The ship is still and the background is whirring by. If that’s in your head with the sound design, you can totally fake it. That opened a whole new road of opportunity for us with shooting.”

Another early season favorite for Aron was “Entombed,” the Indiana Jones-style adventure in which the Bad Batch accompany pirate Phee Genoa on a treasure hunt. The large moving structure that emerges from an ancient temple in the episode’s final act was born out of the episodic director, Nate Villanueva’s, passion for B-movie horror and classic Kaiju movies from Japan. “The wide shots of the walking figure and the camera looking up at it are right out of that,” Aron says. “We did everything we could to emphasize the power of this thing. We watched every Kaiju movie to study them. When the blast goes off and the light goes across the sky, I wanted it to feel like a goliath. Everything became orange and yellow. The dust was coming down. It all came from Nate. He wanted it to go bonkers all of a sudden. I went in and added little explosions to the joints to help sell that it was collapsing even more. We had so much fun.”

And after years working with the masters at ILM and the likes of George Lucas, Aron now gets to experiment with a new role these days: mentor. With new colleagues at Lucasfilm Animation including Alex Shaulis, a technical director, and Kyra Anastasia Kabler, a digimatte artist, Aron and the team form a daily partnership with CGCG to create the stunning imagery of The Bad Batch, where every frame is truly a painting.

Photo by Joel Aron.