Lucasfilm design supervisor James Clyne on finding inspiration from the London Underground, biker gangs, and Frankenstein's monster.

In the name of research, James Clyne strapped on some virtual goggles and took a flying leap off a scaled model of a speeding train.

Lucasfilm’s design supervisor for Solo: A Star Wars Story had designed the conveyex for a heist sequence in the new film, which called for characters to jump from car to car. But when one of the other creators questioned if the gap between segments was too wide to be able to work for the scene, Clyne decided to test the theory himself. Using Lucasfilm’s Virtual Scout technology, typically employed by designers who merely want to take a stroll around a life-size CG model of their creation, Clyne uploaded a model of the train and virtually climbed aboard.

“You put the goggles on and you’re standing on a train car 60 feet up,” Clyne says. The gear was set up in a relatively small office space. “Could I run and try to jump?” he recalls asking. “They were like, ‘Well, we’ve never done that. We usually just have people slowly walking around the room.’”

Clyne had to try. With one person holding the cables cascading off the back of his virtual headset, “I just put my back against the one wall and I ran.” He almost slammed into the back wall, and he almost tripped as he made the jump, he says with a laugh, “but I was able to do it! And I went back and reported back to production, the directors -- I, normal Joe, can jump over that!”

Earlier this week, Clyne gave us a behind-the-scenes glimpse at designing Lando’s sleek Millennium Falcon and a look at the science and creativity that went into the making of the Kessel Run sequence.

Today, in our third and final installment, we get inside Clyne’s head to discuss his vision for a Star Wars on-screen first -- an Imperial train -- and the other elements that make the heist scene in Solo: A Star Wars Story. (Spoiler warning: This story contains some details and plot points from Solo: A Star Wars Story.)

'You don’t want to get shoved under that thing...'

For a film that gives us a reimagined (and incredibly clean) Millennium Falcon, Clyne and his design team tackled plenty of firsts for the latest Star Wars movie.

“You start with the script and it says, ‘Imperial train,’ much in the vein of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” Clyne says. “I’ve never seen an Imperial train! I’ve seen a walker; I’ve seen a Star Destroyer. [The train] was described as possibly being on a laser beam initially, but one thing I had proposed early on was I don’t want it to feel just like a normal train. In true Star Wars fashion, you take something that’s very iconic and you know what it is and then you just kind of flip it on its head.”

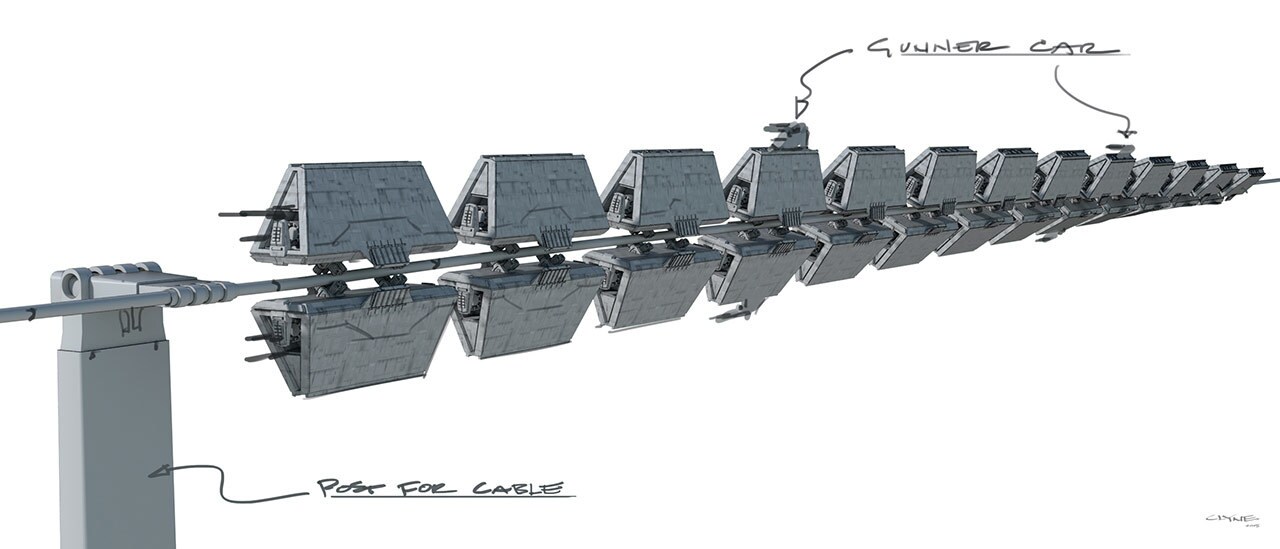

Clyne’s galactic version of riding the rails on Vandor included a train with two cars hugging the tracks, stacked one on top of the other. “My grandfather was an engineer and I always try to bring a little bit of engineering into it,” Clyne says. Beyond the cool aesthetic, the double cars also act as a counterbalance to distribute weight around turns.

Ultimately, the laser beam was replaced by a more substantial chain drive. “We all liked that because it felt dangerous and scary. You don’t want to get shoved under that thing because you won’t make it out of there. And it went with the aggressive nature of the Empire and having this kind of heavy, fortified thing.”

It also gives the characters some additional obstacles. “That played into the service of the story in that they couldn’t actually lift the car off without sliding it off the track first,” and uncoupling the car from the rest of the train itself, Clyne says. “To me, it’s a fun design challenge because again you’re not designing a ship that’s just flying around in space. [The train] has all these constraints against it. There’s gravity, there’s the weight of the thing, there’s…how does it rotate? Does each car rotate individually as it goes around a corner?”

In the grand tradition of Star Wars solutions, the challenge of designing the train went well beyond the machine and the tracks. “It’s not only the train, is it? How does the train mount to the track, and then how does the track mount to the mountainside and then what happens to the track when the train tilts one way or the other? Each one of those problems we had to solve through design. The track is off the mountain and there’s a post that goes down and is driven into the rock….You never see this stuff.” But just like the massive space stations, rebel bases, and ships before it, every last vent that is imagined must have a purpose, even if it’s never viewed onscreen. “You have to ask these questions. There’s going to be a book on that vent,” Clyne jokes.

That attention to detail also gives each component in a galaxy far, far away a feeling of authenticity. “Realism, but also clarity and simplicity,” Clyne says. “Keep the train simple, then the track is simple.”

'Pretty dangerous'

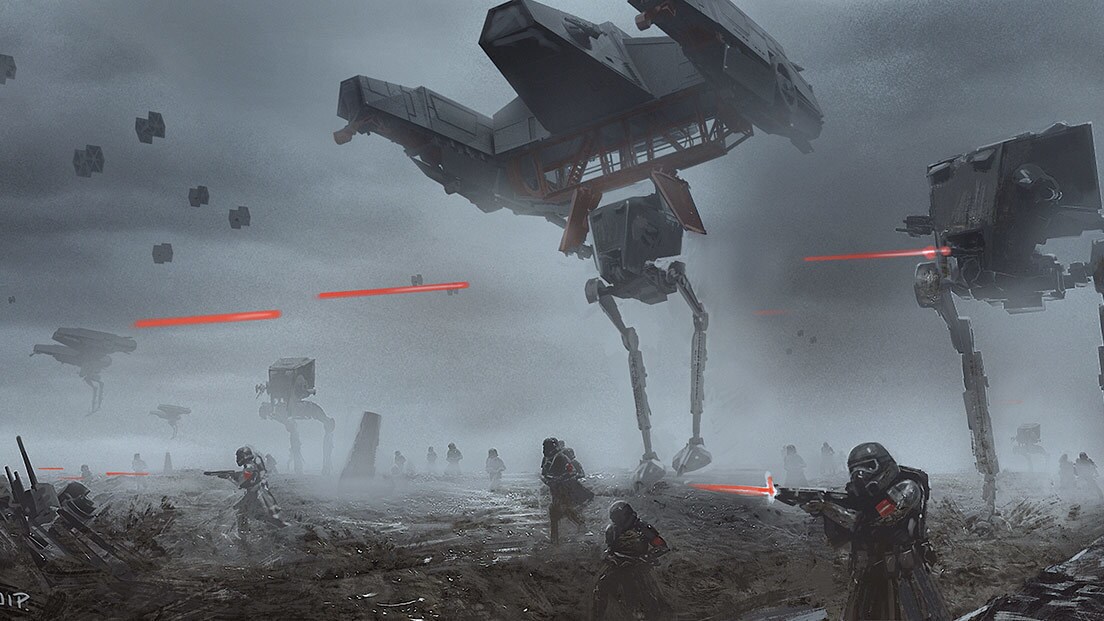

Like the Kessel Run sequence, Clyne once again found real-world inspiration for the look and feel of the train’s locomotion by investigating the London Underground and delving into military history.

The look of the train cars were influenced by German military trains from the '30s and '40s. “These big, heavy fortified German trains,” Clyne says. “That was kind of the impetus. That was the initial vibe of the train. If you look at these things, they look like tanks on a rail that was a big influence.

“Rob Bredow, the now president of ILM and the effects supervisor, took video of Underground trains in London and watched how the cars kind of jiggled their way around a corner. It wasn’t so clean like a monorail or something,” Clyne says. “So we looked at that kind of stuff and then the idea of, well, what does an actor look like on a set with a train on a stage versus a stuntman on a real train? You realize they don’t walk that fast, they’re kind of having to compensate constantly and rebalance themselves so they’re not running. They’re doing this weird shuffle, even though it’s all on a set. It does feel pretty dangerous.”

Filmmakers were also conscious of the delicate dance of putting the camera close to the action, but framing shots in a way that put viewers on the train at times. “Everybody was really conscious, especially with this sequence, that where you put the camera had to almost be a real place. The camera isn’t just floating off in space, it’s mounted on sticks on the train car itself or it’s in a helicopter, but only close enough to where a real helicopter could get. You don’t have these magical camera moves, so a lot of the shots are really close. The hope is that, subconsciously, it buys more into really being there.”

For inspiration, they watched old Michael Mann films like Heat and Thief and screened The Driver, in part to help capture the feeling that Solo was, in many ways, “this ode to '70s filmmaking,” and to break down how the car chase sequences felt so visceral and realistic. “There were a lot of conscious decisions, ‘If we’re going to shoot this for real, where would the camera be?’ And the moment where Beckett has to duck, the camera, I think, has to duck away. It feels like you’re right there.”

Swiss army ship

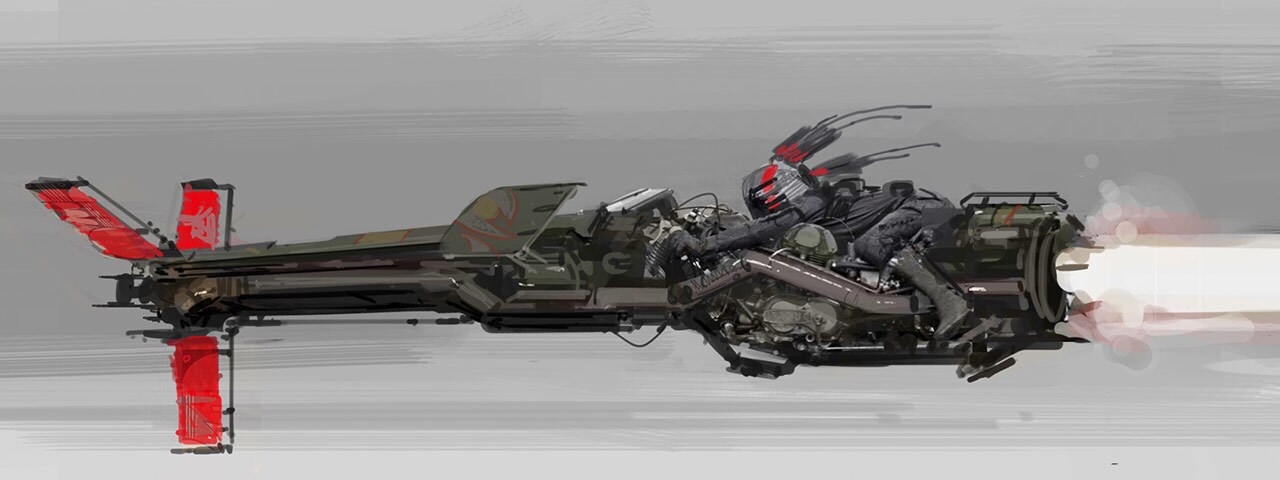

Hovering just above the train itself was the stolen Imperial hauler, which Clyne also had a hand in designing.

“It’s essentially a flying crane, really,” Clyne says. “It’s utilitarian. It’s not the coolest thing you’re going to find [aesthetically], but what I think is cool about it is it’s kind of like a Swiss army knife. It has a couple different functions to it.”

He added a caged gantry to the bottom, which became the spot where Han first learns Chewbacca’s name. “Usually in a spaceship you have just the interior design and then the exterior is a miniature or it’s done on the computer, but I wanted to have an area where it’s really open. That location wasn’t in the script.”