StarWars.com continues its in-depth talk with acclaimed writer, discussing the series premiere of Star Wars Rebels, "Spark of Rebellion."

In part two of StarWars.com's interview with Simon Kinberg, executive producer of Star Wars Rebels, we take a deep dive into the show's one-hour series premiere, "Spark of Rebellion." Kinberg, who wrote the landmark episode, discusses what he's learned from fellow executive producer Dave Filoni, the positive message of the series, and finally getting to scratch a zero-G itch.

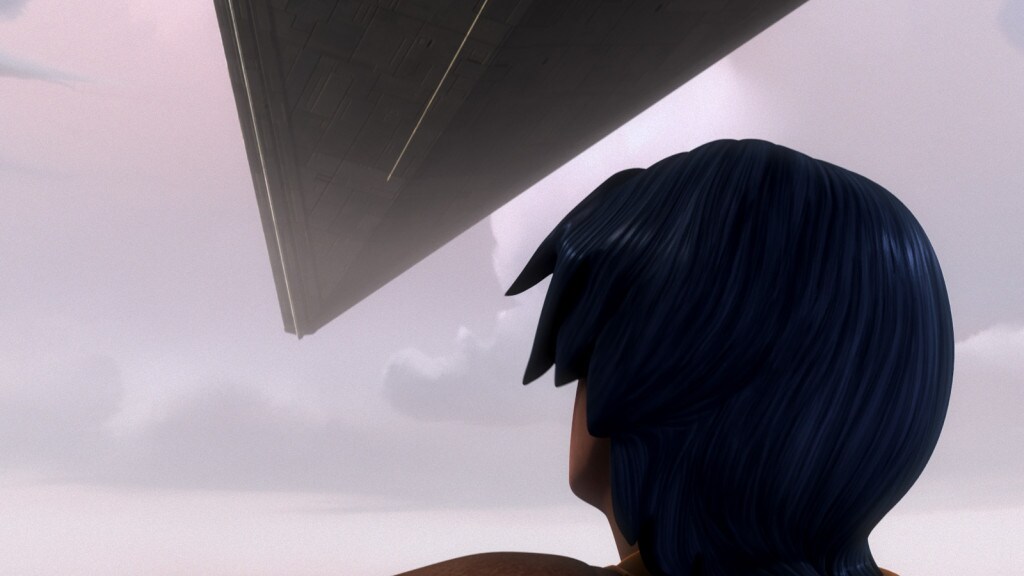

StarWars.com: I’d like to walk through the episode in detail. The first thing that really struck me was the opening shot, with the Star Destroyer passing over Ezra. I saw it as a great visual callback to the beginning of A New Hope, but it makes it much more personal and shows that the Empire has arrived at this planet and has brought tyranny with it. How did you come up with that opening?

Simon Kinberg: Well, you interpreted it absolutely correctly. It is absolutely a callback, a homage to A New Hope, and it is an attempt to, in some ways, ground that image even more in character, and to create a sort of intimacy to go with the epic nature of the shot. But in my memory, it’s not a shot I came to on my own. I think when I wrote my original draft of the script, they were two separate things. There was a shot of a kid, being Ezra, alone on the balcony of this abandoned communication tower where he lives, looking out at the city. And then you see the Destroyers over Lothal [Capital City] to indicate to the audience A) what time period we’re in in the Star Wars world, and B) that, like you say, it’s a world oppressed and a time of tyranny. I believe it was [executive producer] Dave Filoni, as he does very often, who took ideas that were maybe separate or not fully formed, and found a way to dramatize them visually. This is the first time I’ve worked in animation; this is the first time I’ve ever really worked in TV. So I’ve had to have a very steep learning curve about ways of telling stories, because it’s very different than telling a two-hour feature live action. One of the many things I’ve learned from Dave is how to tell the most story in the least amount of shots, and how to tell things even more visually than I do in live action. That’s an example of one where Dave pushed those shots together and created something. You know, we would have the same information if they were separate. But the idea combining these things, it’s not just about information or the efficiency of storytelling, but it’s also about a feeling. I think it’s so evocative of what this kid is feeling in this moment, because it’s also this sense of he’s a little kid against this massive Empire. You get how small that little kid is, standing up on his tower, alone, looking like he’s a dot against this massive landscape, and then with this thing overhead. You get, “How is that kid, by himself, going to somehow lead to a day when those ships can be destroyed?”

StarWars.com: And you understand his attitude of, “Why would anyone fight back? You can’t.”

Simon Kinberg: Totally, totally. One of the things we tried to do with the show, and not in a heavy-handed way, is we wanted it to feel relevant. George [Lucas] has, so brilliantly, made [Star Wars] relevant to the politics and the reality of the moment. So, it’s a galaxy far, far away, but it resembles ours in some ways.

One of the things we hope that people take from the show, especially the next generation, is that you can make a difference. If you really believe in yourself and trust other people around you and question things, you can make a difference. Part of what’s so fun about the show is that you know eventually the Rebels are going to win. I liken it to watching the five farmers that sat in a farmhouse, talking for the first time about the American Revolution. How could a bunch of farmers take on the biggest empire in the world that’s across an ocean? How can we take the power back? It would have seemed almost science fiction to imagine that they could, and yet it was their belief and willingness to sacrifice and trust each other that enabled them to do it. But yeah, you should feel that sense of, “I’m just a little speck in the universe until people treat me differently.”

StarWars.com: From there we see how the Empire has really impacted the lives of the people. They’re bullying street vendors, arresting people for treason. I’m wondering if any of that is based on exploration George Lucas might have done in the past, and how you ultimately came up with the reality of what life is like under the Empire?

Simon Kinberg: The reality of life under the Empire is something that we talked a lot about, and how, especially in those first few minutes, we would dramatize what it was like to be a citizen under oppressive rule. George wasn’t involved, but it’s like, everything that he has built and created informed that. Especially because Dave Filoni has spent however many years he spent with George on Clone Wars, and Pablo Hidalgo has been around George for so long, and knows everything about the way George sees even the minutia of the Star Wars universe. All that information is part of the conversation. What would they be selling in the market, literally? How many stormtroopers would there be per citizen? Things like that. There’s a level of meticulousness, I think, again because the world is maybe more expansive than any other fictional universe out there, that I’ve never seen before. Everything down to the armor, the weapons, the food being sold, and the currency, is really fully thought out.

StarWars.com: Next we’re on to the big opening action sequence, in which the Ghost crew is stealing some cargo from the Empire, Ezra gets mixed up in it, and there’s a big chase. It feels very Star Wars, but also very George Lucas, in that you’re thrown into a scene where you don’t quite understand what’s happening, but you have to keep up. You don’t know who these characters are, but you do eventually find out just through the action.

Simon Kinberg: I love that sequence. The energy, the storytelling, the tone of that sequence is, at least in its intent, pure George Lucas. It is what he did with Raiders, it is what he did with Star Wars movies. It is that feeling that you’re dropped into a fully-formed world, and you’re catching up with these people over the span of an action sequence. It keeps you leaning forward because just physically, the action feels like it’s one step ahead of you, as opposed to you ever being ahead of it. And then emotionally, psychologically, you’re trying to figure these people out and you’re seeing them express themselves in action.

One of the things that I think so many action or adventure stories do is, they have the action/adventure, then they stop for character scenes. Then they have the action, then they stop for character scenes. And there’s a sort of stop/start rhythm to it. That’s fine, but it doesn’t feel fully integrated and I think the world doesn’t feel completely real because it feels like the world pauses for character. As opposed to the way the real world works, which is that it’s where you actually learn and express character.

StarWars.com: You don’t stop being yourself just because you’re doing something action-oriented.

Simon Kinberg: Exactly right, exactly right. I think there are few people who have understood that and expressed that as well as George Lucas. Maybe nobody. So that was definitely what we were trying to do in that sequence. You get a taste of these people and then you start to get more and more of a taste as the action is unfolding. It puts a pressure on the action to not just be fun, video-game action. It has to be doing more than being physically exciting. It just needs to tell more. That was a sequence we spent a lot of time talking about and working on. It was absolutely a group effort between myself, Dave Filoni, all the artists on the show, [executive producer] Greg Weisman. We all put a lot of energy and thought into all of the action sequences, but that one [especially], because it was the place where you were meeting the main characters.

StarWars.com: Even at this early point, the episode really captures that Star Wars feel. The Ralph McQuarrie influence on the visuals is great, but if you just had that, it would be superficial. There’s a lot more to making something feel like Star Wars than just looks. As the writer, and even in your role as executive producer, how do you make sure it feels like Star Wars?

Simon Kinberg: It is something that I’m very conscious of as the writer and as executive producer. And you’re right, just having lightsabers and stormtroopers and Star Destroyers and familiar art wouldn’t make it feel like Star Wars. That would make it look like Star Wars, but it wouldn’t feel like Star Wars. What I think makes it feel like Star Wars is a sort of tone to the characters and to the dialog that George created. I mean, it is a very unique tone. Because on the one hand, it is very fun and bantery, has a lot of comedy, but then it also has really real, scary stakes, as well. And it can delve into darker philosophical issues about good and evil. I think the only answer I can give to that is, it’s a show that is written, produced, and made by people that love Star Wars, and who have a sort of fluency with the language of Star Wars that you need. You can’t be telling a story and then translating it in your head into Star Wars. You have to immerse yourself in that world, in those voices, in that tone, in that attitude, and in the vibe of the films in order to create new scenes that could have been part of the old movies.

StarWars.com: Was there anything in “Spark of Rebellion” where you were having trouble hitting that mark, and then finally got it?

Simon Kinberg: You know, I think the tendency on an animated show that has younger characters than the original movies is to make some of the conflict, like for instance between Ezra and Sabine or Ezra and Zeb, play younger or play a little bit more juvenile. That is the one thing that I think I probably policed and revised the most. Wanting them to feel like young characters, but to have the maturity to make sure that it was bantering, not bickering. That it feels like they have the sophistication, the nuance of the characters we all grew up loving and that the comedy comes from character and not from situation. That to me is the danger. I mean, there are two ways you can go. It can be too serious and too cold, or it can be too goofy and too broad. I found that the danger for me was that things would get too broad and I would reel them in. It’s something that I, and Greg Weisman, and Dave Filoni, and Kiri Hart, and all the people that work on the show, are very conscious of making sure that we maintain that balance.

StarWars.com: Ezra then finds himself on the Ghost starship and realizes he’s in space for the first time. Even though we’ve had Star Wars for over 30 years and have seen people in space a million times now, there’s real impact in that scene and in that moment. Because for a second, you almost feel like, “Oh, I’m in space for the first time.” You can really see it through his eyes.

Simon Kinberg: That is absolutely the intention. Part of the experience, I think, of Star Wars for everybody -- it was when I was saw the movies as a kid, and I’ve seen it with [my] kids watching the movies for the first time -- is that wherever you are, whether you live on a farm or in a big city, you are still transported out of your world into a fantasy existence. Into this other galaxy far, far away. Trying to capture as much of that excitement, adventure, and sort of wide-eyed astonishment, is a huge part of the original movies and hopefully in Rebels.

StarWars.com: Moving forward, there’s the zero G chase. In Star Wars, you always expect to see something new, and this episode did give us a new kind of action sequence with that. Where did that idea originate?

Simon Kinberg: I’ll tell you the truth, a zero G fight or chase is something that I’ve wanted to do in features for a long time. [Laughs] It’s very hard to actually render zero G well in features. They did it really well in Apollo 13, but they used actual flights where they achieved zero G in reality. That’s a hard thing to do for an entire sequence. So, it’s always been a bit of a challenge on the live-action side.

StarWars.com: And animated characters won’t lose their lunch.

Simon Kinberg: [Laughs] No, they won’t lose their lunch, and gravity doesn’t actually take hold until you draw their feet on the ground. It was something I’ve always thought was a cool idea, and I think we all chipped in on that sequence. It’s something you haven’t seen rendered in live-action before, and that’s one of the wonderful things about animation. It’s still complex to build, but the laws of physics don’t apply in the same ways.

StarWars.com: Do you find that aspect of animation to be freeing? To be able to say, “Now I can do this. So, let’s do it.”

Simon Kinberg: Somewhat, but you know, when I’m writing or reading episodes of Rebels, I’m not imagining them as animated characters. I’m imagining them as flesh and blood, real characters. And so, I’m certainly aware, as we’re building the action sequences, of the expansive nature of animation. But I don’t know that I approach them any different than I would if they were live-action Jedi, which have their own set of rules. But in my mind, these are all real characters.

StarWars.com: Yeah. You don’t want to break the believability of something by making it too out there.

Simon Kinberg: No, absolutely [not], and I think that’s part of why people say it feels like the original trilogy. The action, while massive in many ways, feels like it adheres to the laws of general physics.

StarWars.com: In terms of the danger element on the show, there is one moment I found pretty scary, which is when Zeb leaves Ezra behind, and Agent Kallus essentially has him in a headlock.

Simon Kinberg: Like I said, part of what was so transportive about the movies was that they didn’t pull punches. They weren’t speaking down to kids. They felt like kids could handle a certain amount of jeopardy and danger, as long as the movie was clear about who was good and who was evil. That’s the place, as a kid, you feel like, “Okay, well, I understand that these are the bad guys, and these are the good guys, and I’m rooting for and against the characters that the movie wants me to.” So, we felt like the show, especially because it’s animated, could handle a certain amount of jeopardy, danger, real stakes, so that you really believe the challenge of having to take down an entire empire when you’re just five people strong in a kind of tin-can ship.

You also feel the sacrifice and risk that these characters are willing to take and make. I think that’s the critical part, in terms of the jeopardy, strangely. It’s less for the sense of adrenaline in the action, though it’s obviously a part of that, too, and more a sense of “These people are risking their lives.” And I think you have to believe that it’s a life and death risk every week. Sometimes characters will do things like real people that are questionable in their morality when they’re trying to survive. That’s something that we wanted to dramatize from the very first episode, to say that these are not superheroes. They’re actually people, or let’s say individuals, because they’re not all human, but individuals who think and feel and can often act the way we all do.

StarWars.com: Towards the end is a key scene where Kanan ignites his lightsaber for the first time and reveals himself as a Jedi to the Empire. Even though we’ve seen Jedi many times before, that was still a really powerful moment. How do you make sure you get that emotional payoff?

Simon Kinberg: One of the things about the era before A New Hope that’s so interesting is, it’s dangerous to be a Jedi. It is a death sentence to be publicly a Jedi. That is something we took really seriously and wanted the audience -- that may not be as familiar with Order 66 and the rules of the world -- to understand that being a Jedi is automatically dangerous. We wanted them to understand that from the first episode, and taking out a lightsaber is not a casual thing. You are exposing yourself to being hunted down if you are branded as a Jedi. So, that was one thing that we really wanted to do in the episode, and the moment with Kanan needed to do that. It needed to feel like there was no other option for him but pulling out that lightsaber. I think the other part of it is, it’s the first time that Ezra really has seen a Jedi or a lightsaber in action. And we really wanted Ezra, and potentially the audience who again may not be that familiar with what it means to be a Jedi [at this time], to feel that awe.

StarWars.com: Kanan obviously ignited the lightsaber because of the situation they were in, but is he also doing it to show Ezra something about being a Jedi and the responsibility that comes with that?

Simon Kinberg: I don’t know… It’s an interesting question. I mean, I wrote the scene. I don’t know that that’s something I was conscious of. For me, it was the only way out for Kanan in that moment, and there were two consequences that he understood. The one consequence being that he was exposing himself as a Jedi to people that he wouldn’t want to be exposed to, and the other is he’s exposing himself to Ezra. But I never thought of it as teaching Ezra a lesson so much as it was knowing, in that moment, nothing is ever going to be the same with that kid. Kanan and you may be smarter than me, so maybe that was unconsciously part of what he was up to.

StarWars.com: Well, I’ll take that, that as I’m smart as him.

Simon Kinberg: Yeah, you and Kanan are Jedi, so you’re in a different place than me.

Come back later this week for the conclusion of StarWars.com's interview with Simon Kinberg!

Dan Brooks is Lucasfilm's senior content writer, and spends his days writing stuff for and around StarWars.com. He loves Star Wars, ELO, and the New York Rangers, Jets, and Yankees. Follow him on Twitter @dan_brooks where he rants about all these things.